Contents

Guide

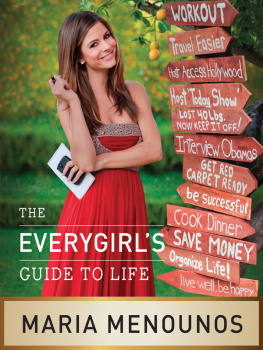

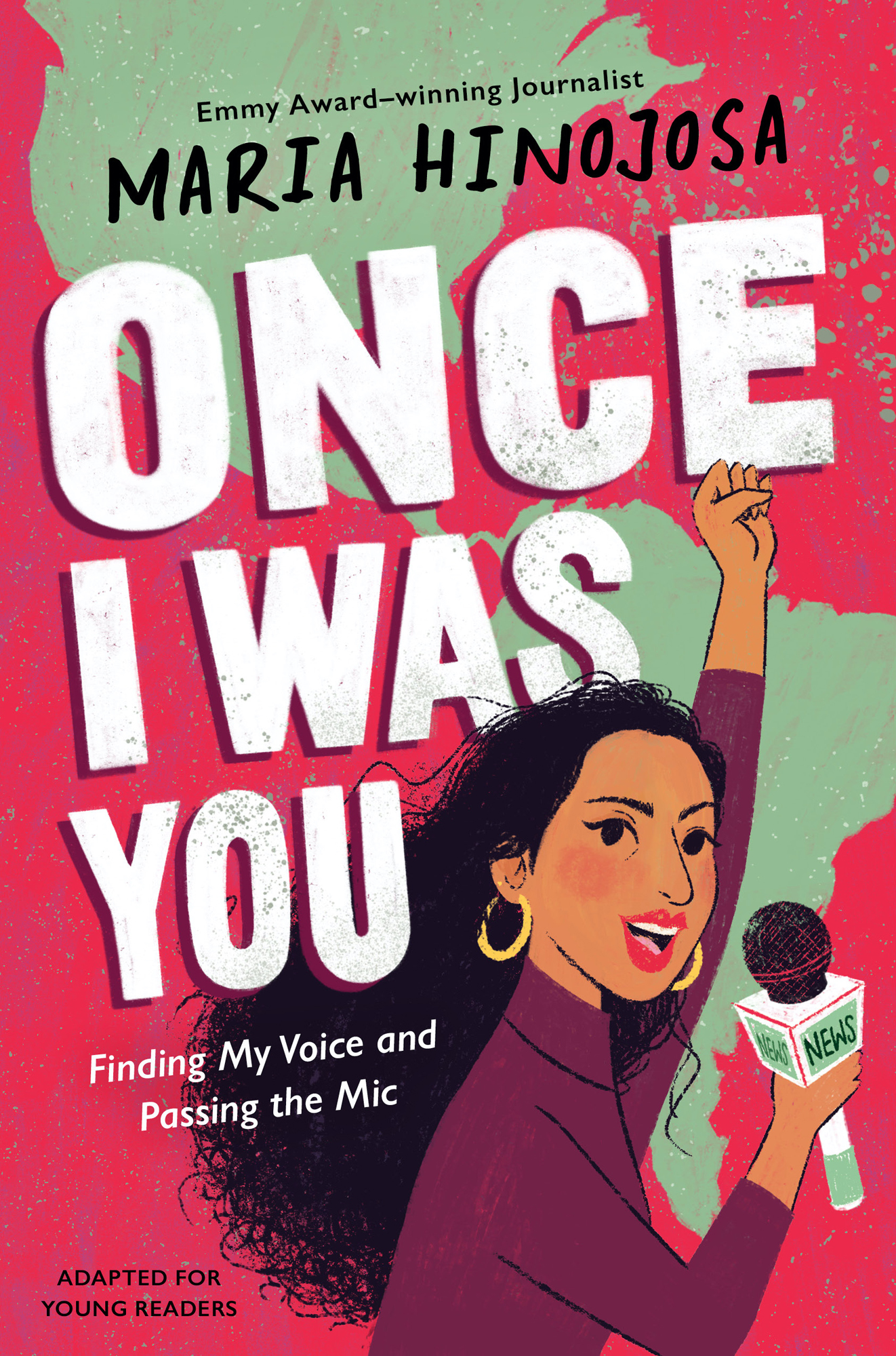

Emmy Award-winning Journalist

Maria Hinojosa

Once I Was You

Finding My Voice and Passing the Mic

Adapted for Young Readers

Praise for Once I Was YouAdapted for Young Readers

I cant stress enough how important it is to read stories like Maria Hinojosas. All the historical horrors of the American immigrant system. All the loving amid the horror. All the imagining of a new world where we all belong.

Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Awardwinning author of Stamped from the Beginning and How to Be an Antiracist

Practically a how-to manual on ways to stand up, be counted, and be heard. Moreover, Hinojosa describes how she came to use her voice to help others. Wepa!

Actress and author Sonia Manzano, Maria on Sesame Street

Electric. Engaging. Once I Was You for young readers is the perfect introduction to complex topics like immigration and racism in the United States. This book is brimming with hope and joy, and readers of all ages will be uplifted by Maria Hinojosas life experiences, power, and incredible storytelling magic.

Gabby Rivera, author of Juliet Takes a Breath

In a voice that is at turns thoughtful and hilarious, Hinojosa takes readers on a ride of not only her own journey toward amplifying her voice but also the journey of an entire family and community demanding to be heard. Full of equal parts feeling and fact, Once I Was You will inspire young readers for generations to come.

Elizabeth Acevedo, author of The Poet X

This is a story of a young woman whose voice has become indispensable in understanding the American experience. And yes, her voice has produced a change in all of us who have stopped to listen to what she has to say.

Benjamin Alire Senz, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe

Maria Hinojosa is hands down one of the most important, respected, and beloved cultural leaders in the Latinx community. Hers is a voice we need to hear at this moment in our country!

Julia Alvarez, author of How the Garca Girls Lost Their Accents

Para mi hija, my one and only daughter, Yurema.

T y solamente t eres mi sol con esa sonrisa de amor.

For all the girls and boys who, like me, werent born in this country and arent going anywhere.

And for my mom, Berta y Bertha. Con amor.

Introduction

I n February 2019, I met a beautiful girl from Guatemala at the airport in McAllen, Texas, which sits near the US- Mexico border. Immigration agents had taken her from her uncle and kept her in a caged-in detention center. Now she was being taken someplace else on a plane. She was terrified and being transported by strangers. But she and I connected, if only for a moment.

She was in shock and looked numb as she waited in the airport along with about ten other kids between the ages of five and fifteen. All of them were silent, dejected, withdrawn, and just plain sad. Thats what most stood out to me about these kids: how sad they all looked.

I smiled and asked her how she was doing. But then one of the handlers, or in my view traffickers, told me I couldnt talk to her. Maybe the girl will remember me because I stood up to the man who was the boss of the group. I told him I was a journalist and that I had a right to speak to the kids. He said no and I answered him back. I spoke up loudly in the middle of the airport and told this man that these children were loved and wanted in this country and that they deserved to have a voice.

That girl is one of the reasons I decided to write this book.

I was not born in this country, but I had the privilege to become a citizen of the United States by choice later in life, when I was about thirty years old. While I love this country because it is home, I also made the decision to become a citizen out of fear that one day immigration officials would turn me away at the border or at an airport when I presented my green card. Its strange to use the words love and fear when you are talking about a country, but I feel both emotions toward my adopted homeland. It is the place where I fully embraced my identity as a Latina and where I learned to ask hard questions as a journalist. The reason Im still here is because I want to help make this country better, and one way I can do that is through my journalism.

Journalists are the people who keep us informed about whats going on in the country and the world. I learned this lesson as a little girl watching the news on TV.

Imagine having a TV the size of a washing machine in the middle of your living room. I know people have BIG TVs now but they are flat. No, the TV sets that I am talking about from the 1960s were huge, clunky wooden boxes with built-in speakers and big knobs. The pictures they showed only appeared in black and white.

My family was lucky enough to buy a used one. Watching the news on that television set was my first interaction with American journalism. The anchors who delivered the news were always white men in suits, white men who spoke English without any accent, without a single hair out of place, and who appeared not to have any feelings. These were the people given the power to tell us what was happening and what mattered in the world.

I watched the news on television every night. By the time I was nine years old, we had bought a color TV that sat in our kitchen where we could watch it from the dinner table. Our familia in Mexico was horrified that we had become those peoplegringos who had a TV in the same place where they ate! But the world was too dramatic not to want to watch. There was a war going on in Vietnam. Protests across US cities. Refugees fighting to survive in their new home. Love and hate playing out in the streets.

But my family, who came from Mexico, were immigrants to this country, newcomers and dreamers, because of my fathers job as a scientist. Our stories, and people who looked like us, were nowhere to be seen on the news or in mainstream media. This made me feel invisible.

I looked for myself everywhere in the media. In Time magazine. On 60 Minutes. In the Chicago Sun-Times. Nada.

I searched through store racks that sold products personalized with names on them. I looked for stickers, buttons, notebooks anything to affirm in the written word that I existed. The displays seemed to carry every name you could possibly imagine, except for one. Mine. Maria.

That feeling of invisibility followed me everywhere I went in this country, the United States of America. The places where I did see and hear people who looked and sounded like me were barrios that looked abandonadosdeserted neighborhoods with no trash pickup, no playgrounds, and broken windows. Still, these places were filled with life and color and the language of love.

Buenos das, Seora!

Que lindo da!

Que le vaya bonito!

Que bello, mi amor!

Mi querida, mi sol, mi vida!

I didnt know it then, but I wanted to tell the stories of the people I saw and knew in the barrio. In the beginning, I didnt know how. I did not feel smart enough to be one of those people on the TV news who appear to have no feelings and never have a single hair out of place. I was the opposite of all that. I was a woman and a Latina. And I had a lot of hair.