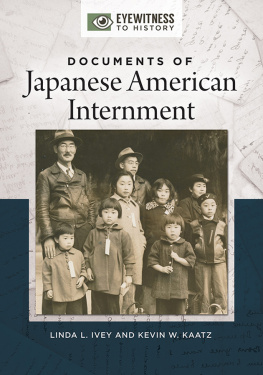

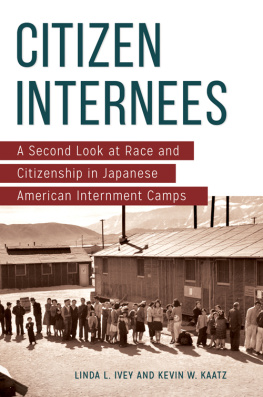

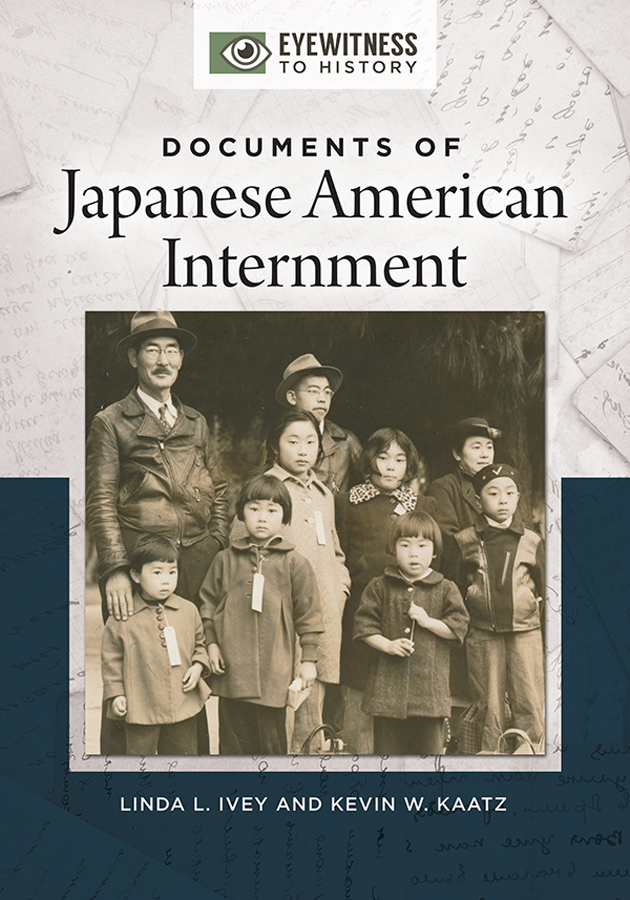

Documents of Japanese American Internment

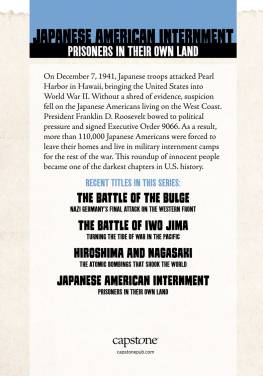

Recent Titles in the Eyewitness to History Series

Documents of the Salem Witch Trials

K. David Goss

Documents of the Chicano Movement

Roger Bruns

Documents of the LGBT Movement

Chuck Stewart

Documents of the Reformation

John A. Wagner

Documents of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

C. Brid Nicholson

Documents of American Indian Removal

Donna Martinez

Documents of the Rise of Christianity

Kevin W. Kaatz

Documents of the Dust Bowl

R. Douglas Hurt

Documents of Shakespeares England

John A. Wagner

Documents of Japanese American Internment

LINDA L. IVEY AND KEVIN W. KAATZ

Eyewitness to History

Copyright 2021 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. The editors and publishers will be glad to receive information leading to more complete acknowledgments in subsequent printings of the book and in the meantime extend their apologies for any omissions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ivey, Linda L., compiler, editor. | Kaatz, Kevin W., compiler, editor.

Title: Documents of Japanese American Internment / [compiled and edited by] Linda L. Ivey and Kevin W. Kaatz.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, [2021] | Series: Eyewitness to history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020003239 (print) | LCCN 2020003240 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440853890 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781440853906 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 19421945Sources. | World War, 19391945Concentration campsUnited StatesSources. | World War, 19391945Japanese AmericansSources. | World War, 19391945Evacuation of civiliansUnited StatesSources.

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 K33 2021 (print) | LCC D769.8.A6 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/1773089956dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020003239

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020003240

ISBN: 978-1-4408-5389-0 (print)

978-1-4408-5390-6 (ebook)

25 24 23 22 211 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

ABC-CLIO

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

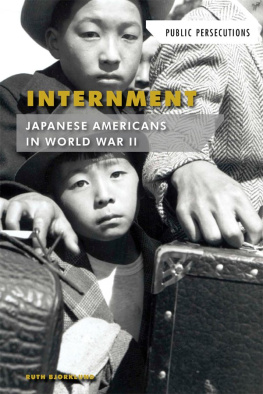

The internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II remains a rather unique moment in U.S. history. It was a government-orchestrated, militarily governed, forced migration of legal U.S. residents out of their homes to temporary prisons, officially in the interest of national security. Nothing else quite like this has occurred in this nations past. The December 1941 attack by Imperial Japan on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor struck a deep chord of fear in the American publica perceived vulnerability that may or may not have been present, and one to which they were not accustomed. Within six months of that attack, over 120,000 residents of the West Coast of the United States had been relocated into internment camps, under the surveillance of armed guards.

One of the chief goals in studying the internment is to try to understand the lessons it can teach us. Among the important lessons of the internment is looking at other events in our history that may have set a precedent for this kind of actionincluding other examples of forced removal or a deep history of discrimination against the Japanese in the United States. It is further critical to think about the impact this removal had in subsequent years and how it may have shaped future government policy. Whether one finds themselves believing that the action was necessary and justified in the arena of war, or that it was an egregious denial of basic civil rights, it has implications for the way our democracy operates. Legal precedents, emergency executive orders, and government recognition of previous mistakes made are all enormous parts of the impact of the Japanese internment on U.S. society today. While the internment is indeed unique, it is not an island unto itself.

The following collection of documents provides students of history with an opportunity to examine this particular moment in political history and in human history. These documents not only tell us about the internment as a political outcome or as an event of government and military response. They also provide insight into the historical experience of the internmentthe human voices that imagined, constructed, and justified the internment and the voices that endured the process and had to re-envision their own sense of safety and security at home.

This investigation into the humanness of the event hopefully inspires empathy and a deeper understanding of the sense of injustice perpetrated. But there is another benefit to hearing these voices as well and one that strikes at the very core of why we study history. In this narrative we can explore both why it happened and how it happened. How did this unfold? Who imagined it, who architected it, and who orchestrated it? And who supported iteither overtly or inadvertentlyby allowing the plan to progress and the architects to execute it? How did our society inevitably allow this to occur?

By exploring the ways in which language and fear directed a nation into supporting a policy ostensibly incompatible with the democratic society it was meant to protect, we seek to untangle the process of this unprecedented action. Further, we hope to leave you to reflect upon relevant, if not essential, lessons for contemporary issues of race, citizenship, and the power of fear.

Many thanks are in order for help in completing this book: Jim Kaufman, a ruthless line editor as always, did so much to streamline our thoughts; Kim Kennedy-White helped usher through the early stages with patience and encouragement; and our families, most notably Doug, Elizabeth and Ivey, tolerated any associated bouts of nuttiness as we balanced locking this down with our university schedules. The research for the book was completed with the support of a faculty support grant from the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs at California State University, East Bay, which allowed us to employ some wonderful student researchers and assistants, including Ivana Kurak, Brooks Moyer, Tyler Rust, J. J. Strauss, Randy Utz, and Rebecca Weber. All talented historians in the making, they gave us some terrific insight and inroads into the vast world of documents available and helped us tremendously with the labor (and love) of discovery. Indeed, we pulled on a long history of document hunting for this book, reaching all the way back to 1991 when Linda Ivey was writing her senior thesis at Trinity College in Connecticut, her first foray into researching the internment, and the library acquired a (then) very recently published oral history collection edited by Arthur Hansen. We came together more recently in pursuit of this story due to the leadership and talents of Kevin Kaatz, who seeded this journey in the Local History Archive Room of the Redwood City Public Library. Most recently, we would like to note, the staff at the National Archives and Records Administration in San Bruno, Californiaespecially Ruth Chanprovided us access to some unique documents that contributed greatly to the idea that incarceration was never a foregone conclusion. We wish to extend thanks to all of the institutions and archivists over the past thirty years who have helped us formulate the ideas to organize and curate this collection. Your work keeps these important voices from becoming forever silent.