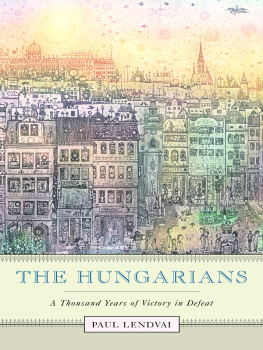

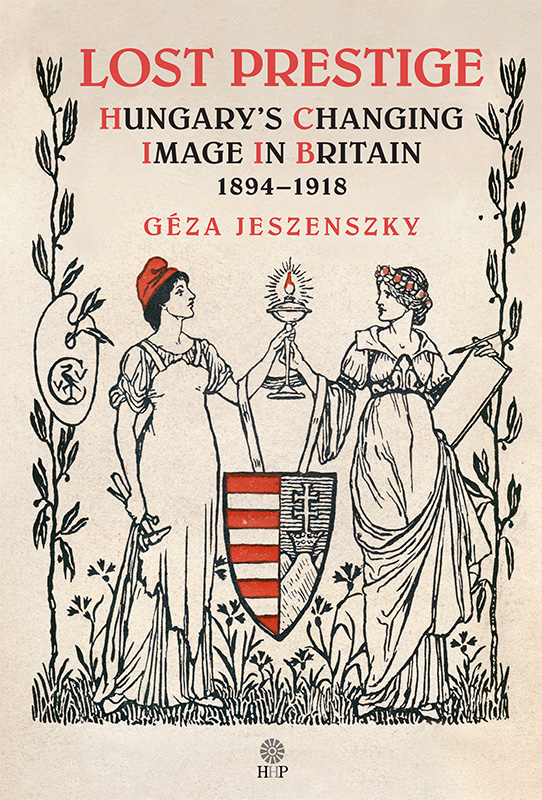

Lost Prestige

Hungary's Changing Image in Britain 1894 1918

Gza Jeszenszky

Copyright 2020 Gza Jeszenszky

Originally published in Hungarian as Az elveszett presztzs in 1994 by Magyar Szemle Alaptvny.

Translation by Brian McLean (from the First Hungarian edition).

Translation edited by Jill Hannum.

All rights reserved

Published in the United States by: Helena History Press LLC

A division of KKL Publications LLC, Reno, Nevada USA

www.helenahistorypress.com

ISBN 978-1-943596-17-1

Distributed by IngramSpark and available through all major e-retail sites.

Order now :

Inquiry:

Copy Editor: Jill Hannum

Graphic Designer: Sebastian Stachowski

Translator: Brian McLean, McLean s Trsa - Budapest

Cover Art: Thanks for permission to publish Dr.Lszl Boka, Director of the Szchenyi Hungarian National Library: Catalogue of Walter Crane collection. Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts (1900)

Preface

I researched and wrote this book (in Hungarian) in the 1970s and early 1980s. It came out in 1986, and a second editionwith an expanded chapter on the war yearsin 1994. Between the first and second Hungarian editions, the political earthquake that shook Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s swept me into politics, first as Hungary's minister of foreign affairs, then as a member of the parliamentary opposition, eventually as ambassador to the United States and, a few years later to Norway and Iceland.

All through those years it had been my ardent hope to see the publication of an English version of this book. My 1994 Hungarian text was translated that same year by Brian McLean, but naturally he left it for me to supply the many quotations from books and periodicals, letters, diplomatic dispatches and minutes that had originally been written in English. I kept intending to fill in the gaps in his translation by inserting the original English, using my notes and documents, but that required a few calm months, and my political duties kept me from that task. Finally, in (formal but still not complete) retirement I could sit down to accomplish what I have considered to be a personal duty.

In the intervening years I had managed to read many, more recent works pertaining to my subject, but I felt that my original text remained relevant, also for English speakers, and do not feel that I ought to revise my book in any substantial way. I have added a few sentences here and there, a few more quotations from British observers, but otherwise I let stand the 1994 translation, revising it only in the very few cases when the translation did not fully reflect my intention.

As I write this, the one hundredth anniversary of the 1920 Peace Treaty signed at the Greater Trianon Palace at Versailles is approaching, and it has generated renewed interest in seeking an answer to how and why Hungary was meted out terms that reduced the historic kingdom to one third of its territory and population, leaving 3.5 million people, Hungarian in language and identity, outside Hungary's new borders to become ill-treated national minorities. My book contributes to the answer by documenting how the very favourable image and considerable prestige of Hungary and the Hungariansestablished in the heroic war of 184849 for a liberal constitution and independence from Habsburg rulewere seriously damaged in the decade preceding the First World War.

My one-time supervisor, the late Pter Hank, a member of the Hungarian Academy of Science, proved to be irreplaceable in all the phases of my research and writing, with his fertile mind. Equally invaluable was the practical and intellectual support of the late Professor Lszl Pter of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at the University of London. Our partly-parallel interests were inspiring and remained so during our hiking and rowing tours in the Carpathians. I owe much to the encouragement and youthful drive of Istvn Gl, an unforgettable fountain of knowledge on Anglo-Hungarian connections and cultural ties between the peoples of the Danube basin. For launching my scholarly career and for his continued attention, I remember Professor Gyrgy Szabad most warmly. The memory of the encouragement I received from my colleagues at the National Szchnyi Library, particularly Jen Berlsz and Gbor G. Kemny, is also most dear for me. I am grateful to the readers of my Ph.D. dissertation, defended in 1980, Professor Istvn Diszegi and the late Imre Gonda for their many comments and recommendations; they were most useful in turning it into this book.

I also owe a lot to my historian colleagues and friends. Among them first mention is due to my grammar school history teacher, Jzsef Antall, who later became the prime minister of Hungary's freely elected, non-communist government in 1990. His government's foreign policy reflected some of the ideas in my book. The advice and comments of many other historians, many since deceased, were also most welcome; they include, in alphabetical order: Lajos Arday, Tibor Frank, Tibor Hajdu, Gyula Juhsz, Gyrgy Litvn, Zsuzsa L. Nagy, Mria Ormos, Zoltn Szsz, Lrnt Tilkovszky, Aladr Urbn and Jnos F. Varga.

Many friends and colleagues outside Hungary also helped me intellectually and practically. Sadly, John Gordon, John Lukacs, C.A. Macartney, Hugh Seton-Watson, Gbor Vermes and Tibor Zsuppn did not live to see the English version of a book to which they had made such a valuable contribution. F.R. Bridge, Valerie Cromwell and Peter Sherwood can also count on my gratitude. The hospitality of Betsy Berg during my researches in the Public Record Office in London was an essential contribution.

To the staff of many institutions, libraries and archives I also owe my gratitude. First among them are the National Szchnyi Library of Hungary and the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Science, where I spent many happy years both on the staff and making good use of their services. Without the materials and the facilities of the National Archives of Hungary, the Public Record Office of the U.K., the Archives of the Times, the libraries of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (today with University College, London), the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the British (Museum) Library this book could not have been written.

The support and help I received from my late parents and also my wife and children was invaluable.

This English-language edition owes a great deal also to the comments, recommendations and scrutiny of the copy editor, Jill Hannum; and it would not have been published without the dedicated support of Katalin Kdr Lynn of Helena History Press.

Responsibility for the book's conclusions is entirely mine.

Budapest, April 2020.

Introduction

Although there has been an unceasing line of contacts between the British and Hungarian peoples for more than a thousand years, the ties have never become close ones, not only because of the geographical distance between the two countries but also because of the absence of any essentially common problems and concerns, or conflicts of interest, come to that. Since the contacts and flows of information between them were sporadic, they gained only meagre knowledge and a sketchy, superficial and even distorted picture of each other. Nevertheless, ties there were, and, consequently, each was on some occasions surprisingly knowledgeable about the other, more so than the present generation would assume. From time to time there was an upsurge in dynastic or religious (mainly Protestant) connections, or later of political, intellectual ormore rarelyeconomic relations, in which cases, more information would flow, but it was still too little to give the public in either country a clear idea of the other.

Next page