Pter Ndas

Parallel Stories

It is all one to me

Where I am to begin, for there I shall return.

Parmenides

I hasten to state that the book in the readers hand is not a historical work but a novel; all the names, characters, events, and situations, however real they may seem, are nothing but the product of the authors imagination.

My gratitude to the Wissenschaftskolleg of Berlin, with special thanks to the excellent librarians of that institution, Gudrun Rein and Gesine Bottomley, for their helpful suggestions and selfless support of my work.

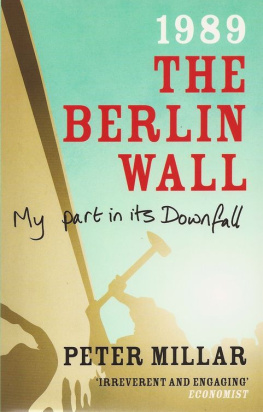

In that memorable year when the famous Berlin wall came down, a corpse was discovered in the Tiergarten not far from the graying marble statue of Queen Louise. This happened a few days before Christmas.

The corpse was that of a well-groomed man of about fifty, and everything he wore or had on him appeared to be of better quality. At first glance a gentleman of some consequence, a banker or a senior manager. Snow was falling slowly, but it was not very cold, so the flakes melted on the paths of the park; only the blades of grass retained a white edge. The investigators did everything by the book and, because of the weather conditions, worked quickly. They closed off the area and proceeding clockwise in a narrowing spiral course searched it thoroughly so they could record and secure all existing clues. Behind an improvised screen of black plastic sheets, they carefully undressed the corpse but found no signs indicating suicide.

A young man who ran in the park every dawn had discovered the body. He was the only one the investigators could question. It had been completely dark when he set out, and he ran almost every day on the same path at the same time.

Had it not been so, had not everything been routine and habit, had not every stone and shadow been engraved in his minds eye, he most probably would not have discovered the body. The light of distant streetlamps barely reached this far. The reason he noticed the body, lying on and half dangling off a bench, was, he explained excitedly to the policemen, because on the dark coat the snow had not melted at all. And as he was running at a steady pace, he related a bit too loudly, the whiteness flashed into his eyes from the side.

While he was talking, several men busied themselves inside the roped-off area. They were working, one might say, in ideal conditions; there was not a soul in the park besides them, no nosy curiosity seekers. Using a flashbulb, one of the men photographed something on the bare, wet ground that two forensic technicians had already labeled with a number.

As he began his story for the third time, the young man noticed nervously that every clue had been numbered and the sight made him very anxious. He felt as if he had been not the one who discovered the corpse or reported it but, rather, the culprit instantly confronted with physical evidence of his crime.

He was like a blade, though he could not tell of what, perhaps of a razor or an icy thought, but of that he said nothing.

In fact, his first thought was that he had murdered his own father. He could not understand why he had such a thought, why he would wish the death of this man, but of that too he said nothing to the police officers.

Hardly anything remained of which he could speak aloud.

But they paid little attention to him; both uniformed and plainclothesmen were going about their business, and from time to time they mumbled to one another phrases the young man could not understand.

They would not delay him further. Twice he had given them his personal data, they had registered his willingness to give evidence later in court, and still he could not leave.

Some of the policemen were being relieved by others around him.

When he runs, he repeated excitedly in his report, he does not look at anything or in any specific direction, and he does not think. From a psychological viewpoint, that is the essence of running at an even pace. But when twenty minutes later he again ran past the body on the bench, it occurred to him that the snow could remain intact like that only on a cooled-off corpse.

He had read something like that somewhere. And thats when he stopped to take a closer look.

In Berlins Tiergarten, or game preserve, many things have happened already, or, more correctly, hardly anything can happen here that hasnt occurred before. The police officers listened to the report impassively. One of them simply moved on with his plastic bags to continue his work. In a little while, another one stopped to listen, and the rest of them promptly left him there alone. However, the young man could not calm down. He told his story to this new man as if every detail had another hundred details and every sentence needed a further explanation, as if with every explanation he were revealing earthshaking secrets while keeping silent about his own.

He was not cold, yet his whole body was shivering. The plainclothes officer offered him a blanket, go on, wrap it around yourself, but he rejected it with an irritated gesture, as if the condition of his body, an impending cold or the awkward and embarrassing shivering, did not interest him in the least. He probably had some kind of nervous fever, a phenomenon not unfamiliar to law-enforcement people. Neither could he be certain of the impression he was making. He felt he was not making a good one, which in turn compelled him to present everything in ever greater detail. This last policeman, however, regarded him with delight, with an enthusiasm bordering on love, as he observed the agitation in the young mans facial features, body, and individual limbs, and his ceaseless gesticulation, wondering whether to think of him as choleric or ascetic, as someone with above-average intelligence and sensitivity or simply as a city idiot interested only in himself.

As a person so starved for speech that he could not stop before tomorrow. As one to whom nothing ever happened but who now was becoming tangled in a suddenly arrived great adventure; as one entrusted with nothing less than the secrets of the universe.

He elicited pity and some worry. In the end he could talk only to this one police officer, but he completely enthralled him with his feverish words, his vehement but disciplined and therefore fractured gestures, and his mental makeup that defied classification.

After methodically scanning the various surfaces and points of the young mans body and attire, and because the observed exterior seemed so average that even its social situation would prove hard to determine, this detective asked the young man which university he was attending and what he was studying, slyly adding that he asked not officially but only as a private person. Theoretically he had no right to pose such a question, but he knew from experience that sometimes a few innocent words will stanch sickly and senseless gushing. The death of strangers can cause real hysteria even in the most endomorphic persons. At the same time he did not mean the question to be a formal one; he was interested to see how the young man might be steered by such an innocent query, how far he might be led from his self-admiration, or perhaps how he could be trapped; how tractable he was. Although he was one of those well-trained detectives who usually avoided being misled by an unexpectedly deep impression or a labyrinthine imagination, the plainclothesman could not resist the experiment, at least to the extent of asking the provocative question.

However, whether with this or some other approach, whether in the first hours of an investigation in police parlance the loop questions, or first forayor at its peak, when the results somehow hang together however precariously, it was impossible not to lose some equilibrium. Here and there, he set little traps. Because detectives like him consider their own ideas preferable to the general criminal procedures used by their less daring colleagues. They were more creative, though their methods were sometimes high-handed. In one professional idiom, they preferred heuristic means to syllogistic ones, and, being guided by the former, they sometimes violated the law.