Contents

Contents

Guide

POST WALL

POST SQUARE

Rebuilding the World after 1989

Kristina Spohr

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright Kristina Spohr 2019

Cover design by Heike Schssler

Kristina Spohr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

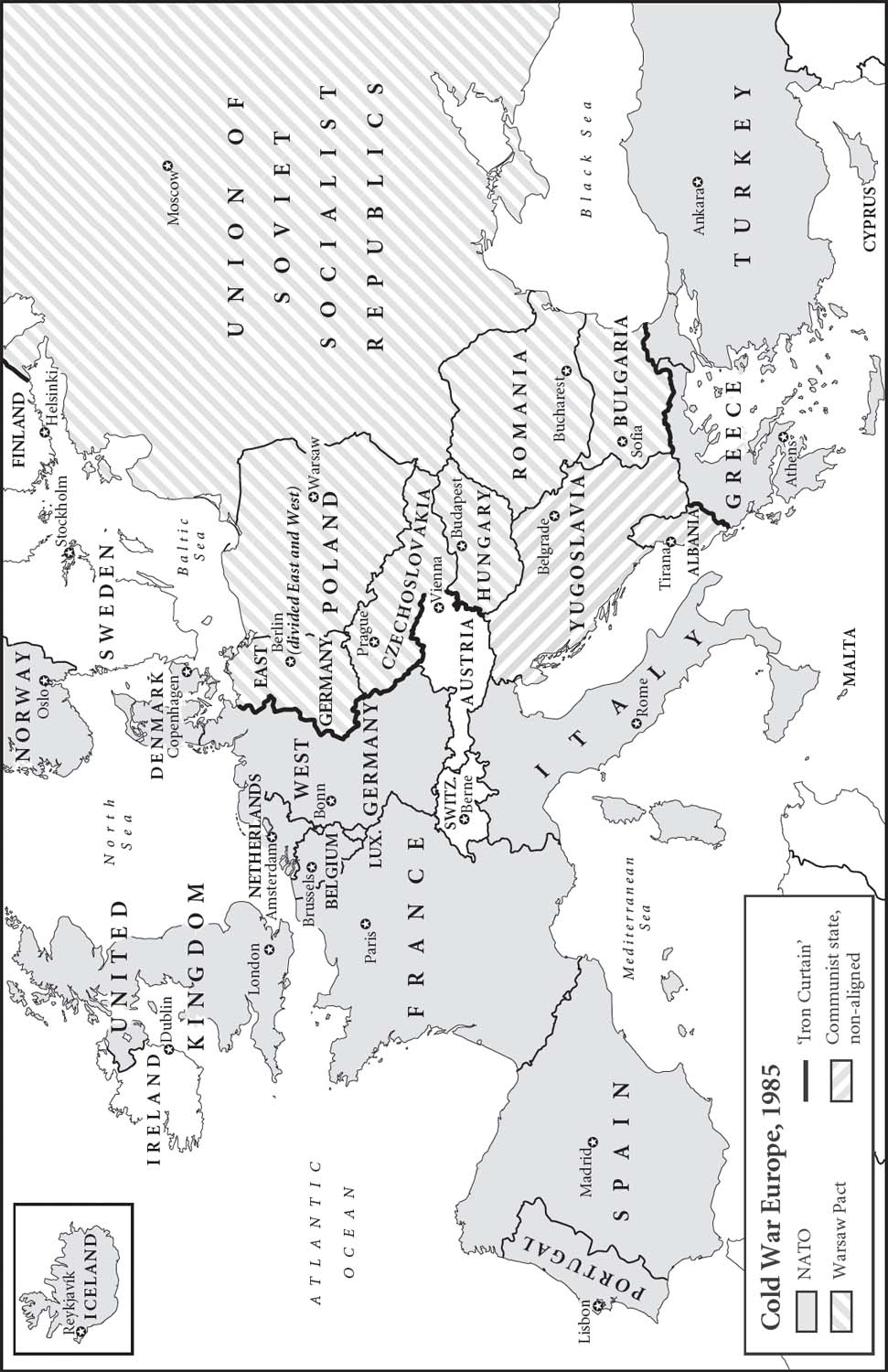

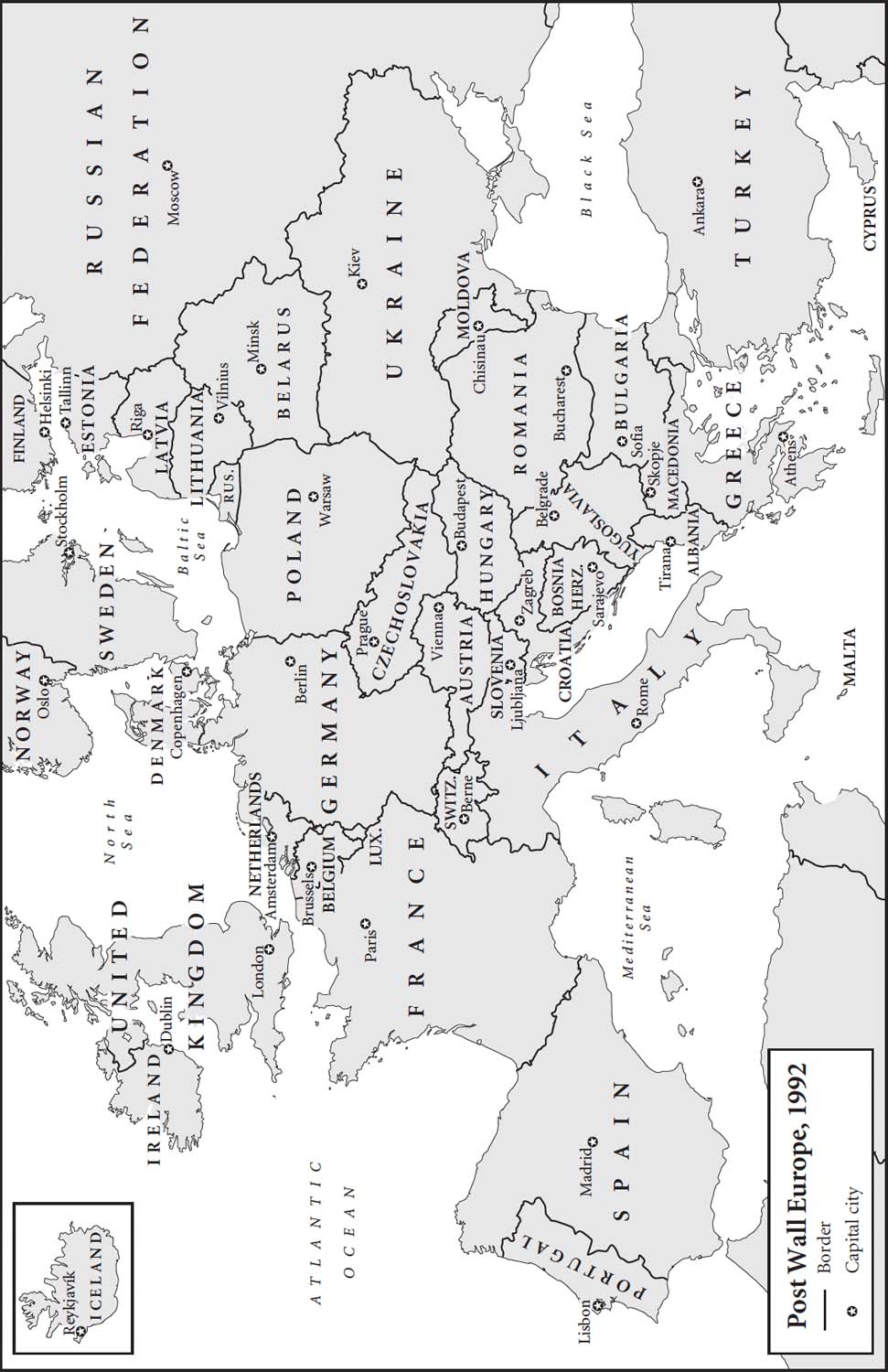

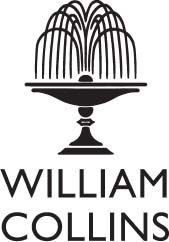

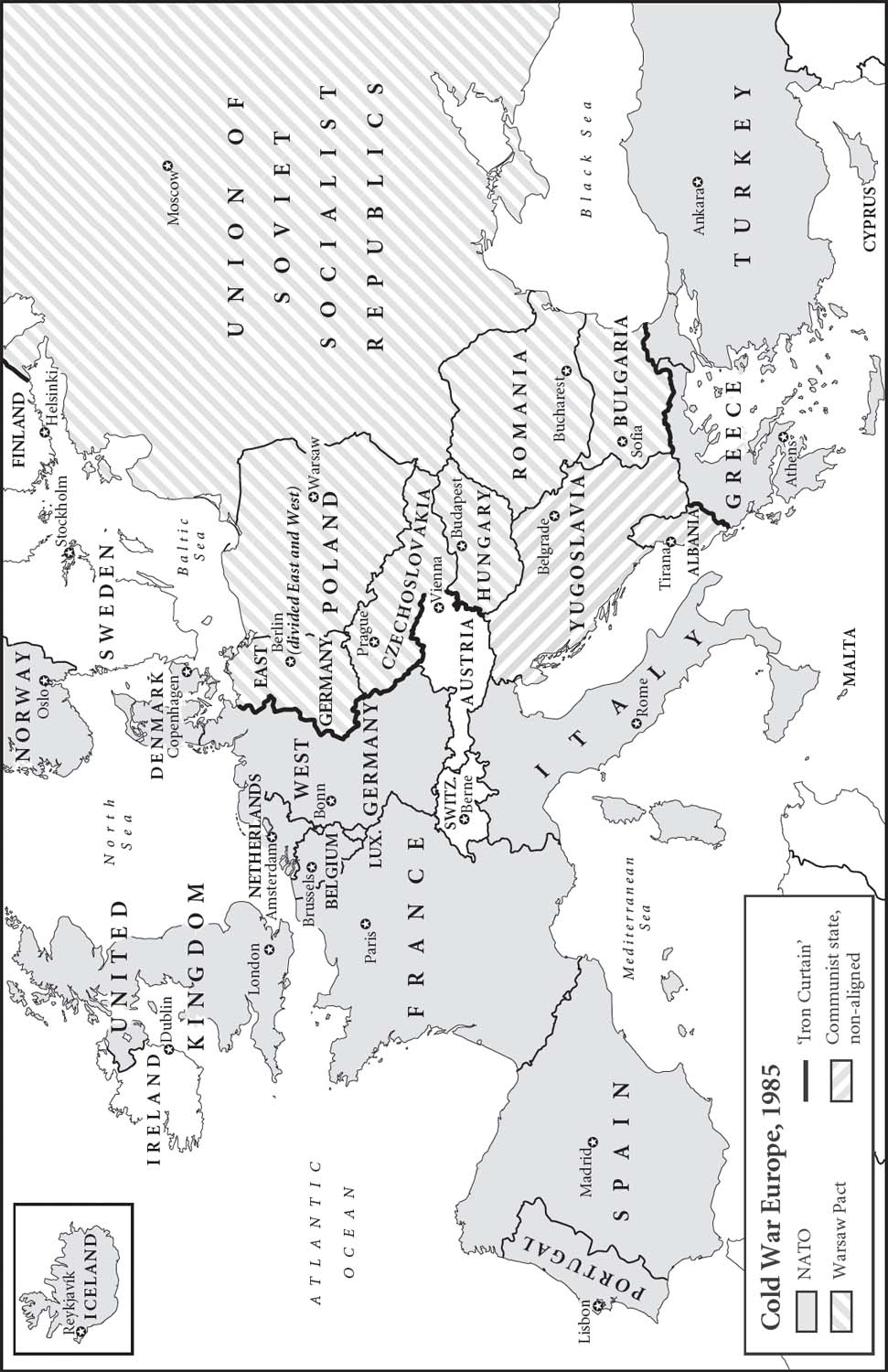

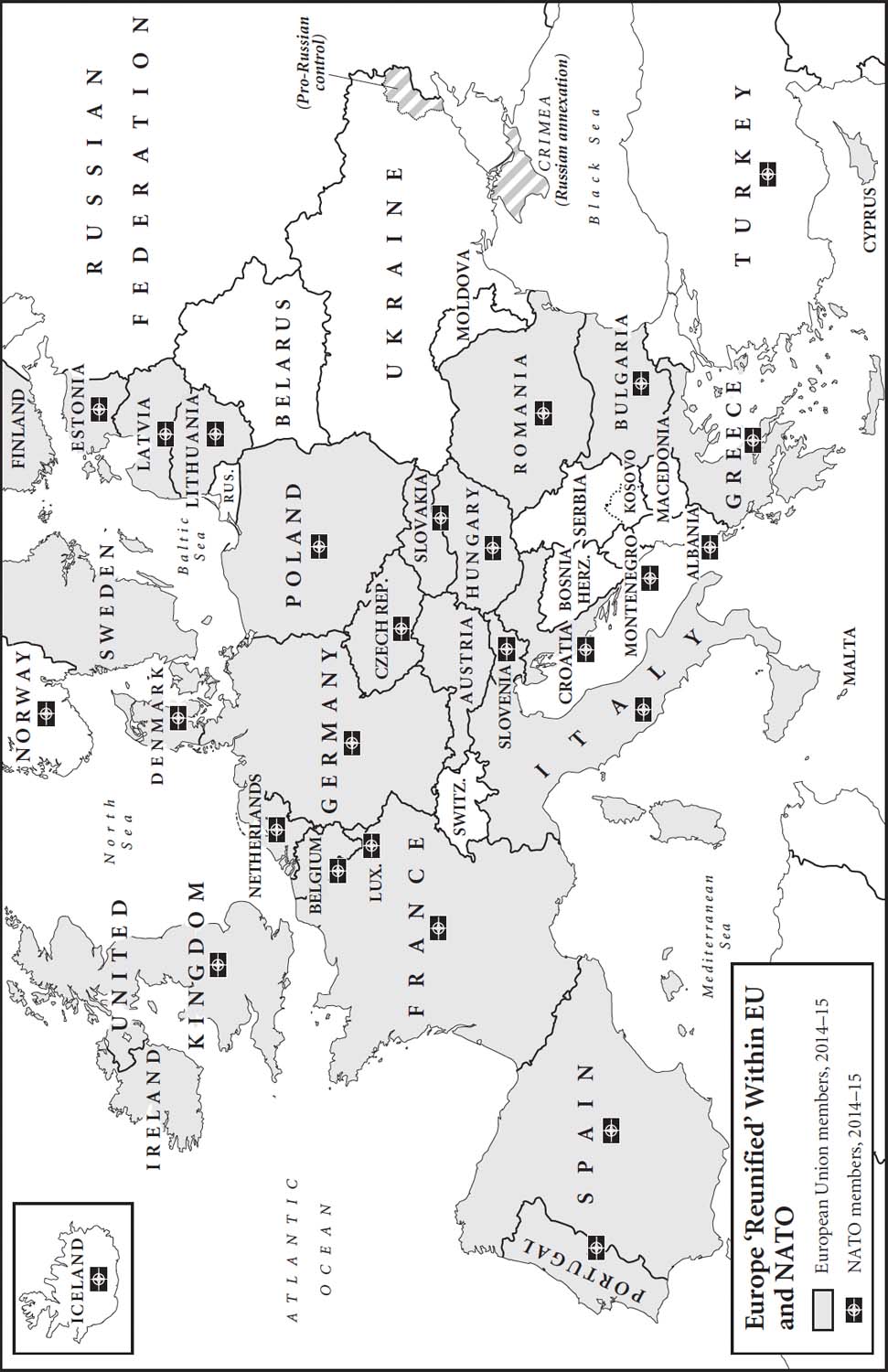

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008280086

Ebook Edition October 2019 ISBN: 9780008280109

Version: 2019-09-11

For my godchildren

Anna Lisa (*1997)

Daniel (*2004)

James (*2007)

Clio (*2013)

born into the post-Wall world

E conomic crisis in the Soviet Union War in the Gulf Chaos in Yugoslavia A Stalinist coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev Mobilisation across the whole Eastern bloc Soviet invasion of the Balkans The West calls up reservists and puts civil defence on highest alert

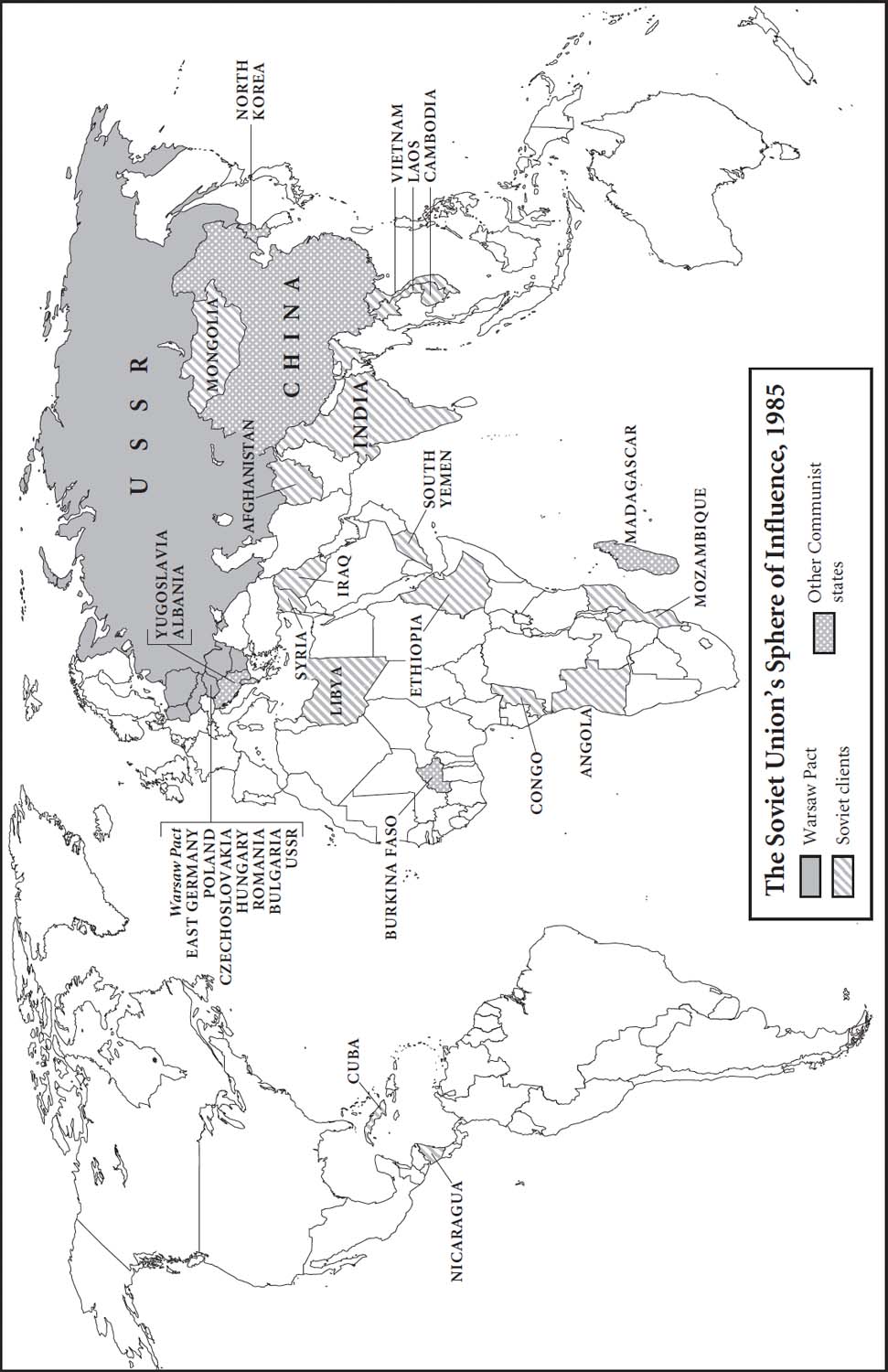

At dawn on 24 February 1989, thousands of Warsaw Pact tanks begin rolling into West Germany, from the Baltic right down to the border with Czechoslovakia. The main attack comes across the North German Plain, with a secondary strike toward Frankfurt. At first Western armoured forces manage to keep the enemy in check, despite a tidal wave of refugees. But then the Kremlin resorts to the use of poison gas against Great Britain and northern Germany. On 5 March, Allied forces start to break and NATO authorises the first use of tactical nuclear weapons. Undeterred, the Soviets press home their attacks, so NATO moves to a second and this time massive nuclear strike on 9 March with twenty-five nuclear bombs and missiles, a third of which are launched from West Germany. The Soviet leadership reciprocates in kind. An atomic firestorm engulfs most of West and East Germany. The radiation spreads across Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary

Of course this was not what really happened. It was the storyline for NATOs biennial Wintex war game. In the 1989 scenario Germany became the theatre of a limited nuclear war, which meant instant obliteration for hundreds of thousands of Germans, and radioactive contamination across the historic heartland of Europe condemning millions more to a lingering, agonising death. Worse, the spectre loomed that localised nuclear conflict might ignite the Third World War.

Even before the war game had begun, the Wintex 89 drill narrative had been leaked to the press and then sensationalised in the German and Soviet media. So appalling was the prospect sketched out in the simulation that Waldemar Schreckenberger the man from the Chancellery chosen to play commander-in-chief (Bundeskanzler bungshalber) during the exercise while the real chancellor was busy conducting West Germanys normal government business refused to launch the second strike in an effort to curtail the human tragedy. As a result, Wintex 89 was prematurely aborted. There would be no more NATO Wintex drills in the future.

At the beginning of 1989 the Western defence establishment still took seriously the prospect that the long superpower confrontation might climax in a global nuclear holocaust. Only a few months later, however, the European future looked radically different. The Cold War did indeed come to an end in a rapid and unexpected fashion but not with the nuclear big bang for which the two armed camps had spent so much time, money and ingenuity rehearsing.

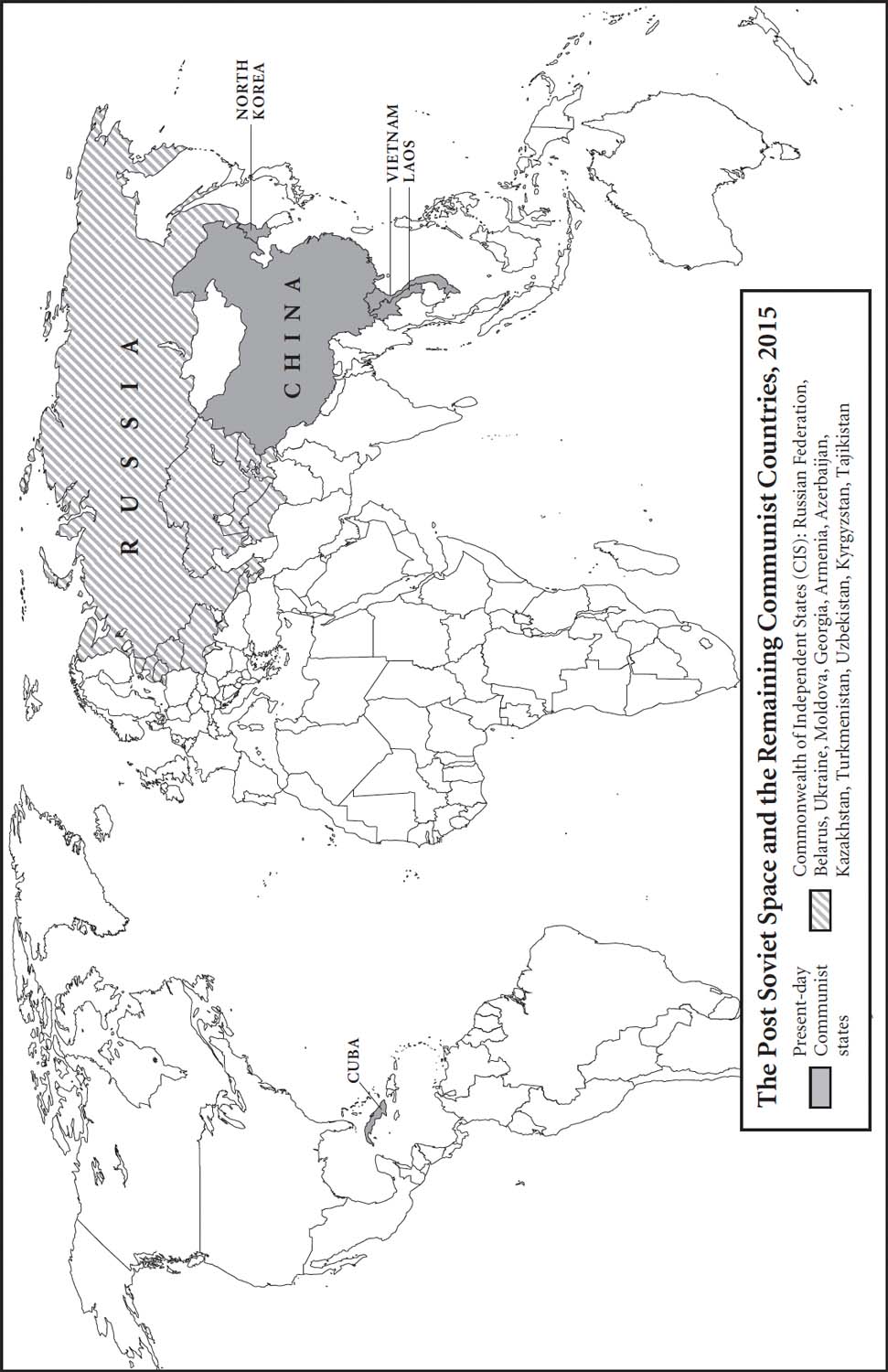

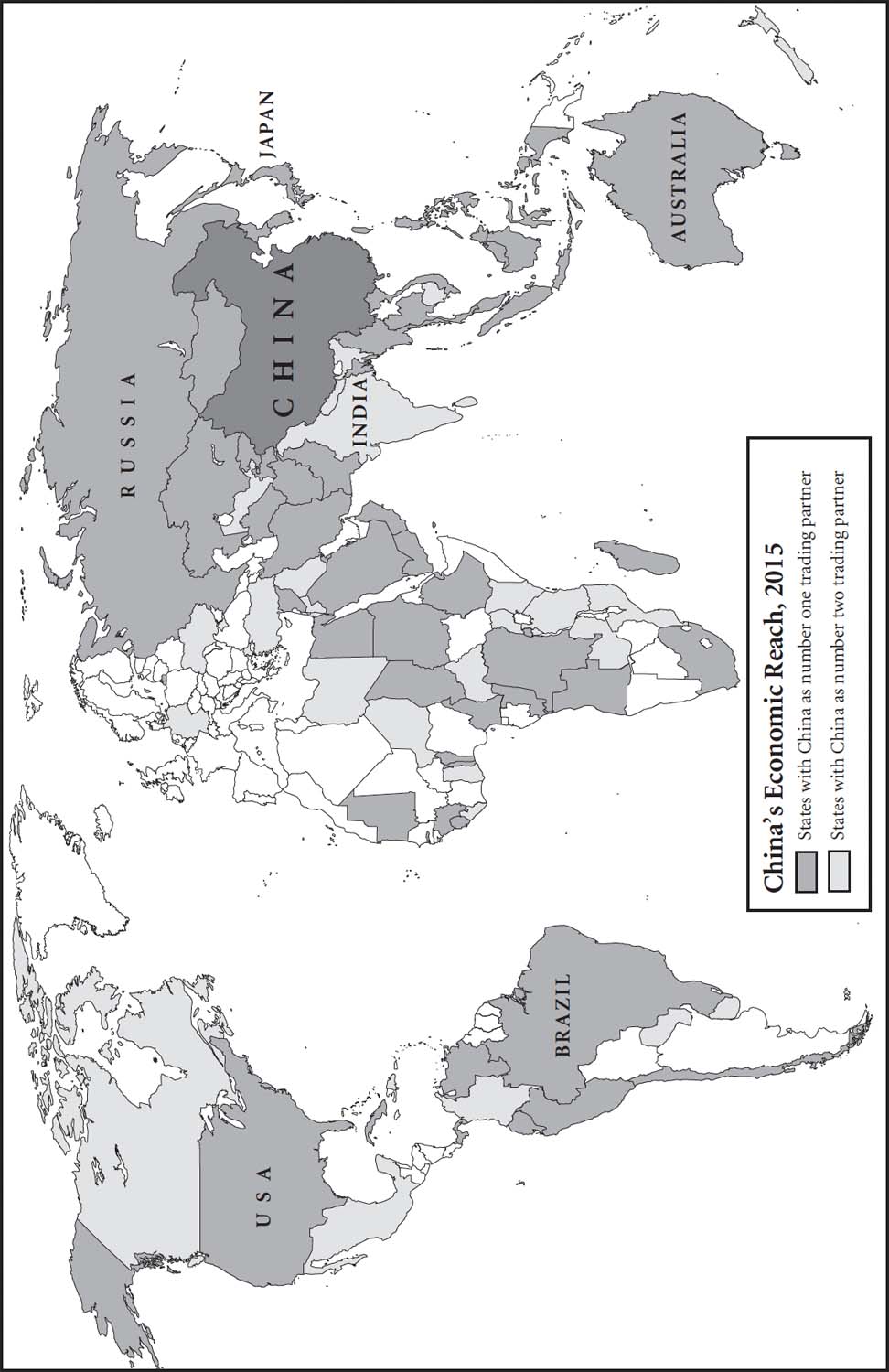

The war between East and West never did take place; the Cold War denouement was a largely peaceful process, out of which a new global order was created through international agreements negotiated in an unprecedented spirit of cooperation. The two chief catalysts of change were a new Russian leader, with a new political vision, and popular protest in the streets of Eastern Europe. People power was explosive, but not in the military sense the demonstrators of 1989 demanded democracy and reform, they disarmed governments that had seemed impregnable and, in a human tide of travellers and migrants, they broke open the once-impenetrable Iron Curtain. The symbolic moment that captured the drama of those months was the fall of the Berlin Wall on the night of 9 November.

In 1989, everything seemed in flux. Currents of revolutionary change surged up from below, while the wielders of power attempted political reform at the top.

Nothing had prepared international leaders for such swift and all-encompassing change. For decades they had played war games like Wintex 89. They had never formulated a scenario for a peaceful exit from the Cold War; at worst they just had a fictive military strategy for surviving nuclear Armageddon or, at best, diplomatic tactics for managing a muddled competitive coexistence between two adversarial blocs. They could scarcely have been less prepared for the actual ending that came in 198991. This book explores why a durable and apparently stable world order collapsed in 1989 and then examines the process by which a new order was improvised out of its ruins.

In order to understand the paths they took and the decisions they made, I peer over the shoulders of key statesmen, watching them struggle to understand and control the new forces at work in their world. These men (and one woman) explored a range of often-conflicting options in an effort to manage events, impose stability and avoid war. Lacking road maps or shared blueprints for a future world order, they adopted an essentially cautious approach to the challenge of radical change using and adapting principles and institutions that had proved successful in the West during the Cold War. This was undoubtedly a diplomatic revolution, but conducted paradoxically perhaps in a conservative manner.