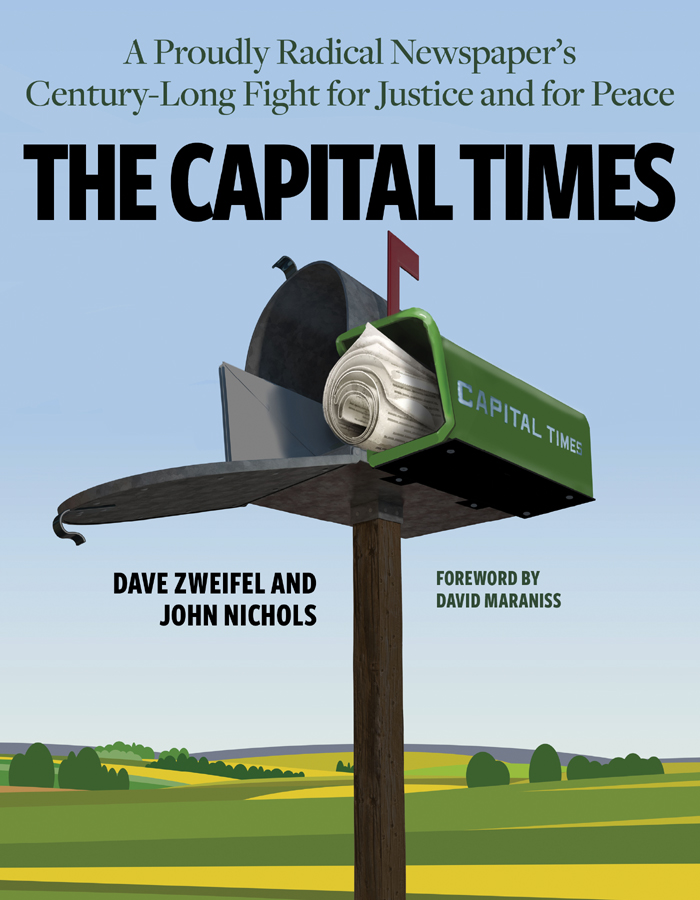

THE CAPITAL TIMES

THE CAPITAL TIMES

A PROUDLY RADICAL NEWSPAPERS CENTURY-LONG FIGHT FOR JUSTICE AND FOR PEACE

DAVE ZWEIFEL

AND

JOHN NICHOLS

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2017 by Dave Zweifel and John Nichols

E-book edition 2017

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a generous grant from The Evjue Foundation, Inc., the charitable arm of The Capital Times.

For permission to reuse material from The Capital Times: A Proudly Radical Newspapers Century-Long Fight for Justice and for Peace (ISBN 978-0-87020-847-8; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-848-5), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

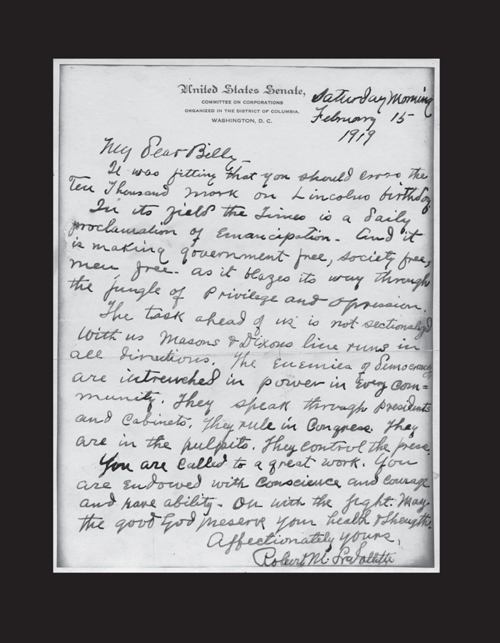

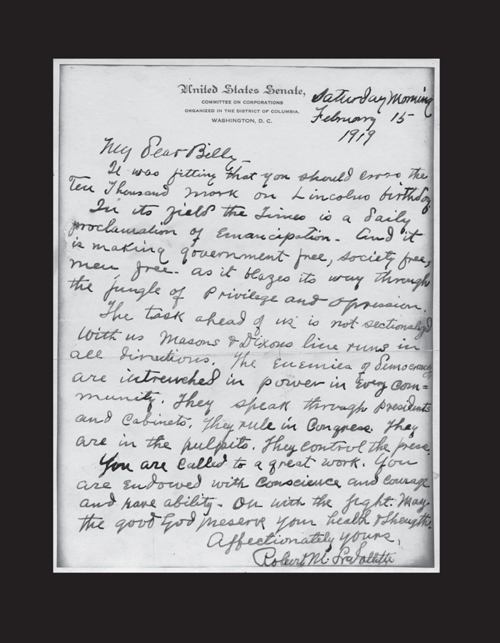

Image of La Follettes letter to Evjue on page ii courtesy of The Capital Times Front cover illustration Courtney McDermott

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Cover and interior design by Diana Boger

21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for.

Let the people have the truth and the freedom to discuss it and all will go well.

William T. Evjue

CONTENTS

The first image that comes to mind when I think of The Capital Times is the old newsroom on South Carroll Street, just down the hill from the Capitol Square. The place was a wonderful mess. Cigarette butts scattered on the floor. Copy editors in white shirts and saggy suspenders hovering on the rim. Glue pots, carbon paper, copy paper, thick black pencils, pneumatic tubes, haphazard stacks of old newspapers and books, and notebooks cluttering the floor and drowning the battleship gray metal desks. The pungent smell of ink and smoke, the clackity-clack-clack-zing of upright typewriters in action. Editors shouting, reporters muttering.

For me as a kid, visiting The Capital Times was better than a trip to the zoo, the characters more exotic. First Id spot Miles McMillinknown only as Macin his downstairs office, chewing and snapping gum with violent velocity, his eyes gleaming, a blinding smile creasing his big broad handsome face, as though he had just snared a state senator in another lie. Then Id skip up the grease-grimed stairs to the delicious chaos of the wide-open newsroom and stare in wonder at the motley crew putting out the daily afternoon miracle: Kreisman and Custer and Marshall and Ryan and Sammis and Wilbur and Meloon and Lewis and Pommer and the Hinrichs twins and Cornelius and Sage and Miller and Kendrick and Zweifel and Gould and a gruff city editor named Elliott Maraniss, my dad, who could read type upside down and scribble seemingly indecipherable scratches on copy that only the back shop could understand. Just as it should be, straight out of The Front Page.

From an early age, I knew there was something different about the paper. My fifth-grade science teacher at Randall School, Parkis Waterbury, made sure of that one day when he declared in class that The Capital Times was nothing more than a communist rag. I remember running home and shaking as I related to my mother what my teacher had said. A preternaturally calm woman, not easily provoked, she blushed her red cheeks a deeper red, stormed out the front door, and marched up Regent Street in search of Parkiss carcass.

The sides were clear in the Madison newspaper battle. On one side was the Wisconsin State Journal, with its support of Joseph McCarthy and the Vietnam War and the establishment in general. Its sports pages were peach, its politics conservative. On the other side was The Capital Times, with its fearless opposition to McCarthyism and the Vietnam War and instinctive support of underdogs everywhere. Its comic and lifestyle pages were green, its politics liberal. When wed go for a family drive on Sundays, my dad made a habit of looking for green newspaper boxes at the driveways end of farm houses along the country roads near Black Earth or Cross Plains or Montrose or Roxbury. He would recount to us all one more time how Dane County had the best soil in the country and how the farmers around there were all old progressives who loved Mr. Evjue, the newspapers founder. He called those farmers and the workers at Gisholt and Oscar Mayer and other factories on the east side of Madison the salt of the earth, and from him there could be no higher compliment.

The Cap Times always wore its heart on its sleeve, or on the front page. It showed no subtlety, whether it was going after a right-wing county sheriff known for drunk driving or a president who had promised he had a secret plan to end a war. The paper would publish story after story, day after day, hammering home the same themes to hold the powerful accountable. As this richly evocative book makes clear, The Capital Times was never afraid to advocate for what it believed in, even as other newspapers hid safely behind a bland faade.

There were, perhaps inevitably, some rough patches for the scrappy little paper, none more difficult than the newspaper strike of the late 1970s. My father had risen through the ranks to become executive editor by then, and though I was on the East Coast beginning my own career in newspapers, I remember him confiding to me many times about how difficult and demoralizing that strike was for him, especially since the paper was not responsible for the conditions that led to it. He loved his reporters, even those who were screaming epithets at him from the picket line. And when the strike was over, he held no grudges; he hired many of them back and made peace with the rest, a reconciliation that seemed wholly in the Cap Times tradition.

If it was a feisty paper that loved to fight, the fights should be with clear enemies of what the paper stood forand there were enough of those to keep it busy: companies that polluted rivers and cut down forests and endangered the natural beauty of the state; university officials who seemed more interested in turning the school into a profit center than a laboratory for the Wisconsin Idea; demagogues who appealed to the worst human instincts of racism and xenophobia; politicians who represented the powerful over the powerless.

On a crisp winter morning in 2008, as I was walking toward DuPont Circle in Washington, my cell phone rang and it was ZweifDave Zweifel, then editor of The Capital Times. From the hesitant tone of his voice I sensed that someone we knew and loved had died. Not quite, but the same emotions came over me as he explained that the paper would cease daily publication and move onto the internet. For some reason the news brought to my mind a long-ago dayit must have been during my fathers first year at The Capital Times in 1957when he announced at the dinner table, You wont believe what I saw this morning. I looked into Mr. Evjues office and there he sat with Frank Lloyd Wright and Carl Sandburg. Imagine that!