Japanese American Ethnicity

Japanese American Ethnicity

In Search of Heritage and Homeland across Generations

Takeyuki Tsuda

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2016 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tsuda, Takeyuki, author.

Title: Japanese American ethnicity : in search of heritage and homeland across generations / Takeyuki Tsuda.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016011168| ISBN 978-1-4798-2178-5 (hbk. : alk. paper) | I SBN 978-1-4798-1079-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

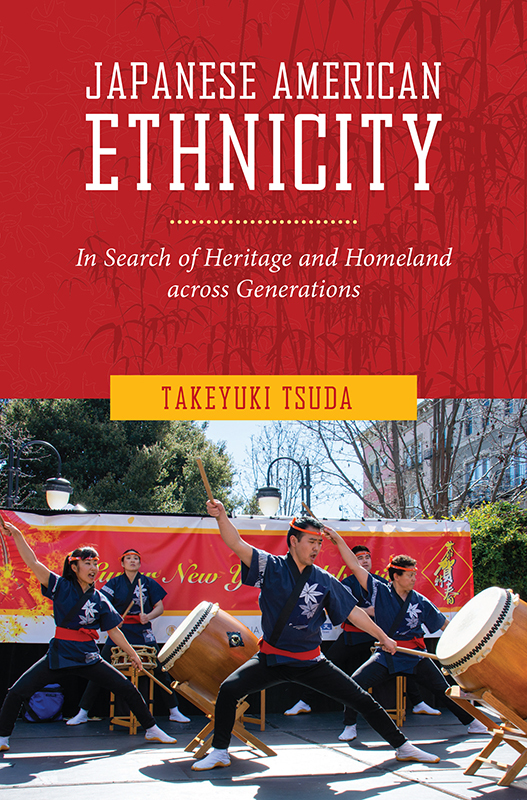

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese AmericansEthnic identity. | Japanese AmericansCultural assimilation. | Japanese AmericansSocial life and customs. | Japanese AmericansRacial identity. | United StatesEthnic relations. | United StatesRace relations. | Taiko (Drum ensemble)United StatesHistory. | Children of immigrantsUnited States. | JapanEmigration and immigration. | United StatesEmigration and immigration.

Classification: LCC E184.J3 T7873 2016 | DDC 973/.04956dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016011168

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

The fieldwork and writing for this book project have been long in the making. I have been sidetracked a few times by other research projects and opportunities, which led to edited book volumes. As a result, I did not initially embark on writing an entire book on contemporary Japanese Americans from scratch, but worked on independent papers on specific topics. The dominant theme and framework for this book therefore coalesced over a number of years.

This book would not have been possible without the supportive and collegial academic environment provided by the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University. A sabbatical that the school granted me during the spring semester of 2014 allowed me to finally finish the book manuscript.

The ideas and analyses contained in this book have benefited considerably from feedback I received at various conferences, workshops, and departmental colloquiums. I thank the individuals who invited me to these occasions and the audiences for their helpful comments and questions. I would especially like to acknowledge the comments and suggestions I received from James Eder, Lieba Faier, Jon Fox, Nelson Graburn, Harlan Koff, William Kelly, Sangmi Lee, Karen Leong, Wei Li, Cecilia Menjvar, Tariq Modood, Luis Plascencia, Claudia Sadowski-Smith, and Hung Thai, as well as Wisa Uemura and Franco Imperial (of San Jose Taiko) and two anonymous reviewers for New York University Press, who provided very thoughtful and extensive comments on the manuscript. Parts of the Introduction, Chapter 4, and Chapter 8 were previously published in Anthropology Today, Ethnic and Racial Studies, and the Journal of Anthropological Research. I thank the editors and reviewers at these journals for their helpful comments. As always, errors in fact and interpretation are the sole responsibility of the author. I would also like to gratefully acknowledge my editor at New York University Press, Jennifer Hammer, for her enthusiasm and support for this project and for her effective and efficient work behind the scenes.

Most importantly, my heartfelt gratitude and deepest thanks go out to the many Japanese Americans in San Diego and Phoenix who so openly welcomed me to their communities and generously allowed me to share their lives and experiences through numerous conversations and interviews. I truly appreciate their willingness to talk to me for hours and their thoughtful comments and insightful observations about their lives, without which this book would not be possible.

Ethnic Heritage across the Generations: Racialization, Transnationalism, and Homeland

Four Generations of Japanese Americans

Ruth Morita is a serious and soft-spoken second-generation Japanese American woman in her seventies. Although she can be quite engaging in conversation, she is not naturally talkative, and it took some coaxing during our interview to get her to elaborate on some of her experiences. Like other elderly nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), she had been interned in a concentration camp during World War II. Because the internment is such an integral part of the Japanese American experience, Ruth assumed that I wanted to interview her about it. Although I had told her that I was mainly interested in the contemporary ethnic experiences of Japanese Americans, she brought a copy of a PBS documentary that had brief footage of her in an internment camp with other girls. I couldnt believe it, she said. I was watching this documentary one day and I see this child running around in camp. I was like, wait a minute, thats me!

Because it is such an important part of her past, I asked Ruth in some detail about her internment experience. I was surprised that she actually characterized it as fun and like a long summer camp. It was a safe environment, she was together with a lot of other Japanese American kids, and she was no longer under the control of her parents. She spent her days going to school and playing with the other girls and made some really good friends whom she continues to see today. She had no stories of misery and oppression to tell, which I had fully expected to hear. Nonetheless, Ruth spoke about how the interment had been a defining moment for Japanese American nisei:

Despite being American citizens, we were locked up just because of our Japanese ancestry. So the niseis had to show they were loyal Americans. Thats why the men went off and fought in the 442nd [the Japanese American Regimental Combat Team that fought very bravely during World War II in Europe]. We stressed being American and assimilation, and didnt want the cultural baggage of our parents. It wasnt until after the war that we were gradually accepted and finally given opportunities to get ahead.

I then asked Ruth about her parents and their internment experiences. It wasnt that bad for the kids, but it was really tough for my parents, Ruth recalled. They lost everything, their business, the house, their possessions... Her voice started to crack with emotion. It devastated them. After camp, they had to restart their lives again with nothing. I dont think they ever completely recovered from it. I dont think the emotional scars ever healed.

***

Steve Okura was a board member of the Nikkei Student Union (NSU), the Japanese American student organization at the University of California at San Diego. The first time I encountered Steve was in the hallway of the student center before one of NSUs meetings. He was speaking to a student from Japan in fluent Japanese. His Japanese sounded so native, I was not sure whether he was Japanese American since I had heard that some students from Japan are members of NSU. I asked Steve during the meeting, Are you Japanese?