ALSO BY STAN COX

Sick Planet: Corporate Food and Medicine

Losing Our Cool: Uncomfortable Truths About Our Air-Conditioned World (And Finding New Ways to Get Through the Summer)

Any Way You Slice It: The Past, Present, and Future of Rationing

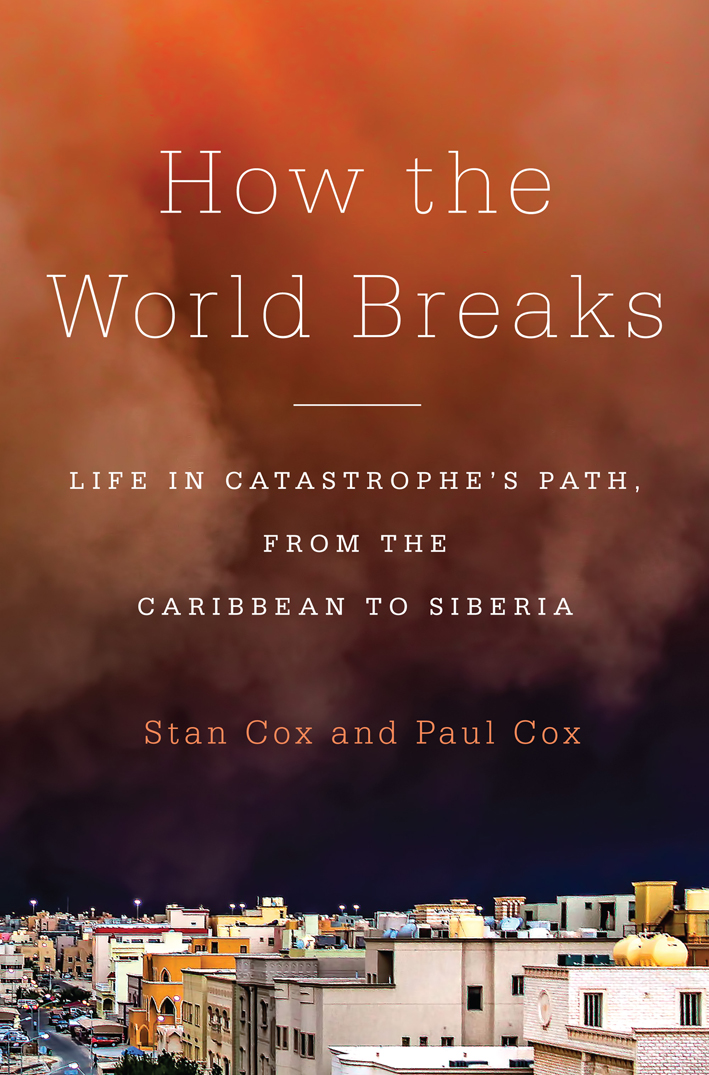

2016 by Stan Cox and Paul Cox

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2016

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-013-3

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

All illustrations by Priti Gulati Cox

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Minion

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the memory of Lucille Brewer Cox

and all the others who lost their lives in Gainesville, Georgia,

and Tupelo, Mississippi, in the tornadoes of April 6, 1936

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

For the invaluable help and insight they provided us, we want to thank John Araneta, Francisco Artigas, Florian Boer, David Bowman, Henry Briceo, Richard Davies, Celeste de Palma, Gudi Devi and Kunwar Singh, Mauro Dolce, Philip Drake, Colin Foord, Vineet Gahalaut, Charlie and John Giordano, Goldi Guerra, Nicole Hernandez Hammer, Peter Harlem, Ilya Jalal, Michael Jarvis, Leigh Johnson, Sachin Kadam, Phil and Christie Le Breton, Sharon Louden and Vinson Valega, Lilah Mejia, Arnoud Molenaar, Marilys Nepomeche, Delacey Verne Peter, Amy Peterson, Seetharam, Sherwin, Nadja Tchebakova, Harold Wanless, Judith Weis, Zelma White, and Andrew Whitehead. Our warmest gratitude for exceptional guidance as we worked to understand and find our way around the world of disaster goes to Stacy Barnes, Judith Buhay, Warren Cassell, Chris Cook, Bob Dixson, Elena Kukavskaya, Ted Lefroy, Janine Lester, Warner Marzocchi, Gean Moreno, Bruce Mowry, Tony Mukiibi, Pheonah Nabukalu, Debra Parkinson, Kerry Paul, Evgeniy Ponomarev, Dwinanto Presetyo, Hardi Prasetyo, Gray Reid, Donaldson Romeo, Phil Stoddard, Mark Tingay, and Adarsh Tribal. We are deeply, deeply thankful to Jed Bickman and Sarah Fan at The New Press, who, in the bleak aftermath of Sandy, made this book possible, and then two and a half years later made it a much better book. This would be a different and much poorer book without the unequaled talent and countless hours that Priti Gulati Cox invested in the making of maps that are both beauteous and terrifying. And as always, our warmest, deepest thanksfor love and support through the writing of this book and the many years before thatgo to our families: Vinita and Cmde. Sahi, Santosh Gulati, Maurya and Bob Farah, Brenda and Tom Cox, Marylaverne and Jerry Bramel, Paula Bramel and John Peacock, Sheila Cox, and most of all the respective loves of our lives, Priti Gulati Cox and Amanda Farah.

Ramala Khumriyal ran a small eatery and shop for pilgrims next to Kedarnath Temple, one of the holiest shrines to Shiva in all of India. He would spend his summers working here with his children, high in the Himalaya ten miles from his hometown, Guptkashi. Then in June 2013, after a period of extraordinarily intense rain, a natural glacial dam melted and collapsed above Kedarnath, emptying a swollen lake and bringing 15 million cubic feet of freezing sludge down upon the settlement. Khumriyals shop was just high enough on the mountain slope above the temple for him to see catastrophe coming. Turning his back on the muddy, rocky tide swallowing up thousands of people below him, he had time to dash upslope into the forest, pulling his six children with him.

Up on the mountainside, it was still raining, and the chill was intense. Bodies were strewn everywhere. Those still alive seemed to be in an altered state, moving as if drunk, some collapsing right in front of Khumriyal. Many survivors spoke of a poison gas that they believed came out of the earth, choking some people and killing others; Khumriyal told us that he and his children felt severe shortness of breath. Having escaped the flood only to plunge himself and his children into the unknowns of the forest, he began wondering if they might have been better off dying down below. The only way back to the nearest town, Gaurikund, was to walk, or stumble, cross-country through some of the worlds steepest and most rugged landscapes. What in normal times would have been a ten-mile trek took, by his guess, twenty-five miles of meandering to avoid cliffs, landslides, and flash floods.

When he and his children reached what was left of Gaurikund, it was already thronged with survivors, and all were trapped. The road down the mountain was gone. The disaster was much larger than Khumriyal knew: the extreme burst of rain and floods had scoured villages and collapsed mountainsides far, far down the Mandakini River and the rivers it joined, all the way into the plains, where it swelled the mighty Ganges. In the stranded town there was little food other than a few cookies, packets of which were selling for four times the usual price. Tens of thousands of tourists and pilgrims waited, hoping for rescue helicopters to arrive. Others, including Khumriyal and his family, became impatient and set out walking again.

When they reached the swollen Vasukiganga River, a tributary of the Mandakini, the bridge was completely gone. A tall tree, however, had caught on the rocks in such a way that its trunk just reached the other bank. Though half submerged in the torrent, it was the only hope for getting across. Evacuees were lining up to make the crossing. Out of each group of half a dozen or so people who attempted to cross on the tree, Khumriyal estimates that two were taken by the flood. He saw the crossing attempt as the last of many tests that he and his family had been given by Lord Shiva in the past days; the presiding deity of Kedarnath, he believed, was separating the pure from the dead. Khumriyals whole family passed the test, and they made their way safely into the town of Sonprayag, which offered some food and shelter despite being largely buried, and eventually found a way back to their home in Guptkashi. The journey home had taken six days.

Seven months later, Khumriyal had become a partner in a small soap-making business in Gaurikund with assistance from the organization iVolunteer, which fosters small-scale development. Asked if he or others who had previously served the tourist industry in Kedarnath would return for the next season, he answered, People who had a child or family member die there surely dont want to return. They know they can make money there, but is it worth the lives of their family? He was hopeful his new venture would work out so that he would never have to go back to Lord Shivas abode. I think about it every day. I have nightmares about it. Even if I went back up the mountain with you, I would not go beyond Sonprayag.