Introduction:

Situating Digital Methods

This is not a methods book, at least in the sense of a set of techniques and heuristics to be lugged like a heavy toolbox across vast areas of inquiry. It is also not the more contemporary exemplar of the instruction manual or list of answers to frequently asked questions, one that would describe how to operate the multipurpose software package by which a number of statistical and network analyses may be performed once the web data set has been collected or delivered separately. Rather, this book presents a methodological outlook for research with the web. As such it is a proposal to reorient the field of Internet-related research by studying and repurposing what I term the methods of the medium, or perhaps more straightforwardly methods embedded in online devices. For example, crawling, scraping, crowd sourcing, and folksonomy, while of different genus and species, are all web techniques for data collection and sorting. PageRank and similar algorithms are means to order and rank. Tag clouds and other common visualizations display relevance and resonance. How may we learn from and reapply these and other online methods? The purpose is not so much to contribute to their fine-tuning and build the better search engine, for that task is best left to computer science and allied fields. Rather, the purpose is to think along with them, and learn how they handle hyperlinks, hits, likes, tags, datestamps, and other natively digital objects. By continually thinking along with the devices and the objects they handle, digital methods, as a research practice, strive to follow the evolving methods of the medium.

Second, digital methods not only think with online devices. They also take stock of the availability and exploitability of digital objects so as to recombine them fruitfully. When studying a web device, building a new tool, or making an interface on top of an existing one, the task is to list the elements at ones disposal, e.g., tweets, retweets, hashtags, usernames, user locations, shortened URLs, @replies, etc. (for Twitter, the microblogging platform). How may the digital objects be combined and recombined in ways that are useful not so much for searching Twitter but rather for social and cultural research questions? Does a particular hashtag, and its set of most retweeted tweets, organize a compelling account of an event, and whose?

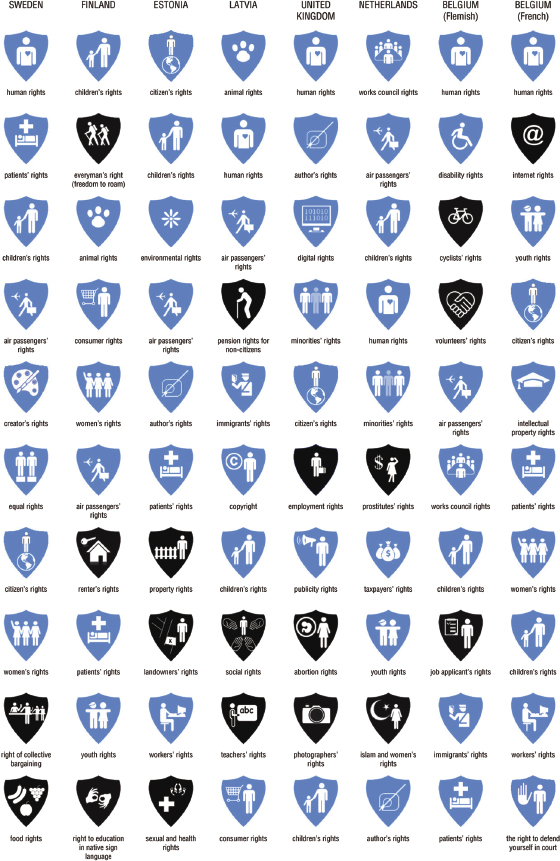

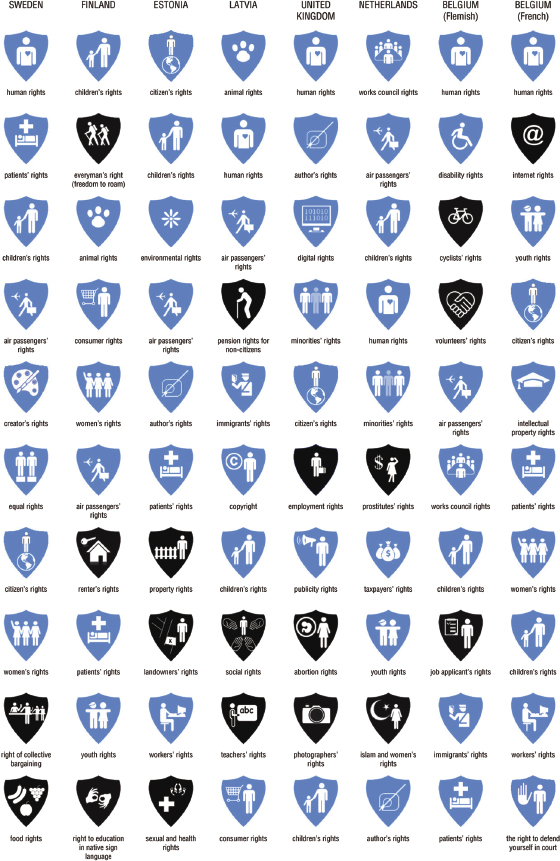

Figure 0.1

Rights types: the nationalities of issues. Top ten rights per country, based on a query for [rights], in each of the languages of the local-domain Googles, July 2009. Digital Methods Initiative, Amsterdam, 2009.

The third principle is to build upon the existing, dominant devices themselves, and with them perform a cultural and societal diagnostics. Digital methods repurpose or build on top of the dominant devices of the medium, and in doing so make derivative works from the results, figuratively and literally. That is, the initial outputs may be the same as or similar to those from online devices, but they are seen or rendered in new light, turning what was once familiara page of engine results, a list of tweets in reverse chronological order, a collection of comments, or a set of interests from a social networking profileinto indicators and findings.

Sources are ranked high in engine results pages not only because they are helpful in providing information to the user for the query made. Their ranking also follows extensive link, click-through, freshness, linguistic, textual, and geographical analysis, which may be vetted by qualitative coders checking a small sample of results. Source rankings also carry social significance in an issue or subject area, and certain sources may grow or decline over time, indicating shifting commitment and appeal. Reading Google results, one may see information and even some of the workings and authorings of Google (including optimized and manipulated results), or one may see societal conditions (see on search as research). As I will develop below, this book largely concerns the latter.

One may undertake a similar exegesis for social media sites such as Facebook, and situate digital methods a second time. In this case, I would like to draw into relief not the difference between everyday use of a device and a trained eye pouring over results, as we just did with Google. Rather, I would like to contrast two web research outlooks. For example, ones newly made friend has numerous other friends, together with an active news feed as well as a well-groomed profile, comprised of considered interests in movies, music, books, and television programs. Playground, high school, college, and other clique and social formations may be organized on that platform, and there will be measurable levels and potentially new forms of sociality driving changes to them. After all, software is running social life, in part, and that can be reflected upon. If one were to think along with the device and examine the available digital objects to be recombined, however, the researchers work changes. One may think too with the device makers and the containers they furnished for users to fill in profiles. How to reassemble the objects (friends and profiles) and repurpose the output of the device (friends profiles and activities) so that it can provide indicators and make findings about (political) culture? One may consider reaggregating the profiles in telling ways. What do the collective interests of the friends of Barack Obama, as against those of the friends of his presidential opponents, tell us about the culture wars? Are political leanings aligned with taste and preference divisions, or are the divides far less great when seen through the expression of media preference (broadly defined)? Are social media sites for the study of shared taste?

Put differently, this is a book about Internet research that is not solely about the Internet. In keeping with a general move toward studying web data (as I come to in the conclusion), the book seeks to provide an aim for Internet research that has yet to be made explicit: the development of a methodological outlook and mindset for social research with the web. In other words, it seeks to move Internet research beyond the study of online culture and beyond the study of the users of ICTs only. In the following chapters, digital methods are put forward for working with the tiny particles (hyperlinks) and the large masses (social media). The book in fact could be read as a history of Internet-related research, as it has evolved from hyperlink and individual website analysis and directory-making in the mid to late 1990s (chapters ). The chapters reflect upon how each of these is often studied, and how else they might be studied if the principles of digital methods were applied.

Digital methods also strive to provide web research with a problematic to work with. The fourth principle of digital methods involves the problem and challenges of employing web data for social research, for it reopens the question of the site of the baseline. Where are the findings to be principally grounded? More specifically, are the findings to be grounded in the online? Or is it necessary to calibrate them or compare them with a traditional (offline) data set or site of study? One can frame this issue by comparing two projects: Google Flu Trends and a map of allrecipe.com users Thanksgiving recipe queries. These are both digital methods projects, but they work with two different ideas of a baseline.

Google Flu Trends (since 2007/2008) is a classic and teachable case of thinking through the availability of natively digital objects (search engine queries, and the places of those queries), and repurposing engine results for social research (the places of the incidence of flu). They show the places of recipe queries, and in doing so a distributed geography of taste or recipe preference across the United States. Whereas for years search engine companies would publish the top queries per month and per year, occasionally categorizing them according to top-level subject matters (e.g., political queries) and giving them trend-spotting, marketing-style project names such as buzz and zeitgeist, the recipe query maps add to the search engine results analysis not only the location of the queries, but also a social research outlook. They display where people seem to like which food. Here the question is whether the researcher would turn next to the offline (telephone surveys, or perhaps supermarket sales data), or continue with online data, grounding the findings further there. Could findings made with search engine queries be grounded through a study of additional web data, e.g., geo-tagged Thanksgiving food photos? Digital methods do not necessarily seek to ground (all) findings in the online, but rather to pose the question of the webs status as potential grounding site.

Next page