Moss - Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940

Here you can read online Moss - Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Endeavour Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Moss: author's other books

Who wrote Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

NINETEEN WEEKS

NORMAN MOSS

Copyright Norman Moss 2014

The right of Norman Moss to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2003 by Houghton Mifflin Company

This edition published in 2014 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

FOR TONY AND PAUL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A NUMBER OF PEOPLE helped me during the writing of this book and deserve my thanks. My agent, Jill Grinberg, believed in the project when I first put it to her and helped get it going in the best possible way. At Houghton Mifflin my editor, Eric Chinski, handled my authors ego sensitively and made helpful suggestions, and copy editor Gary Hamel saved me from some embarrassing errors. I received help from the staffs of several libraries and research centers; in particular, the staff at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, found some documents when I had only the vaguest idea what I was looking for. James Freund lent me a college thesis, Professor Frederick Rudolph of Williams College lent some papers on campus feeling in 194 0, and Mrs. Hazel Hucker lent some family letters that proved useful. My friends Murray and Mary Drabkin provided hospitality and a base in Washington, D.C. And my wife, Hilary, provided unwavering support and encouragement.

We fight by ourselves alone. But we do not fight for ourselves alone.

Winston Churchill to Parliament, July 14, 1940

* * *

What a wonderful thing it will be if these blokes do win the war. They will be bankrupt but entitled to almost unlimited respect.

U.S. military attach Raymond E. Lee, London, July 30, 1940

* * *

We are living as people lived during the French Revolution every day is a document, every hour history.

Sir Henry Channon, M.P., June 10, 1940

* * *

The American people mistook our sheltered position behind the British fleet and British continental diplomacy for the results of superior American wisdom and virtue in refraining from interfering with the sordid differences of the Old World.

George E Kennan, American Diplomacy 1900 - 1950

* * *

INTRODUCTION

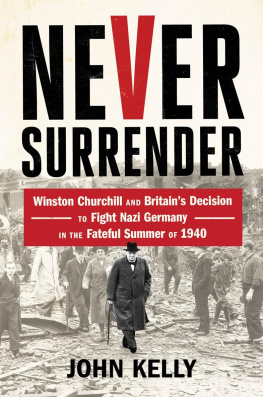

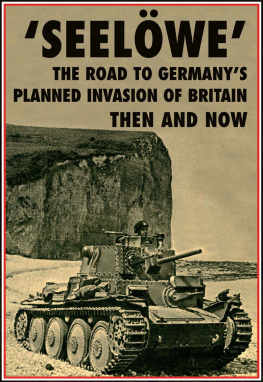

The world changed forever during nineteen weeks in the spring and summer of 194 0. Nazi Germany conquered France, Belgium, and Holland in one of the most astonishing military victories in history. Britain faced the possibility some said the likelihood of defeat. Americans felt for the first time since the birth of the republic that events in Europe threatened their own safety. In the last weeks of the summer the Royal Air Force and a determined British population turned back the most immediate threat of invasion, and the United States committed itself to Britains defense. This commitment introduced a change in the policy the United States had pursued since George Washingtons day and began the countrys permanent involvement in the affairs of Europe.

The period can be dated precisely. On May 1 0, Germany launched its blitzkrieg and Winston Churchill became British prime minister. In the second and third week of September the tide was turned in the Battle of Britain, Germany called off its plan to invade Britain, and the United States supplied Britain with fifty destroyers and received bases in the British West Indies and Newfoundland.

In September of that year Hitler offered Britain a compromise peace, and Britain rejected it out of hand. Hitler was baffled. His deputy f uehrer, Rudolf Hess, took this up with a university lecturer in geography and occasional journalist named Albrecht Haushofer. The two men knew each other because Haushofers father, Karl Haushofer, a military man and academic, had been Hesss mentor at university, and his ideas on geopolitics had influenced Nazi thinking. Albrecht Haushofer, he knew, had travelled widely and knew Britain well.

Hess pointed to the deal over the West Indies bases and said it seemed that Britain, instead of accepting a reasonable peace offer from Hitler that would have left its empire intact, was prepared to hand over its empire to the United States and bankrupt itself in order to continue the war. Why was this?

Haushofer recorded the conversation in his diary. He wrote: My reply was: because Roosevelt is a man who represents a worldview and a way of life that the Englishman thinks he understands, and to which he can become accustomed, even where it does not seem to be to his liking. Perhaps he fools himself, but that at any rate is what he believes. A man like Churchill, himself half-American, is convinced of this. This feeling pervades the workers no less than the plutocrats. The Fuehrer, on the other hand, represents a point of view which is quite alien to the Englishman, and which he believes he detests. (Haushofer was executed by the Gestapo in the last days of the war.)

Haushofer offered an explanation not in terms of realpolitik but in terms of national sentiment. And he was right. Usually, when terms like defending democracy and friendship are used in international relations, they cloak motivations of national self-interest. But this was one of those rare occasions in which national feelings about such things were important. British and American attitudes to democracy, to dictatorship, and to each other, both among those in government and the general public, were crucial in determining their countries policies.

But Hess was also right. By continuing the war, Britain was indeed ensuring that it would become something close to bankrupt and that its imperial power would pass to the United States. Britain ended the war greatly weakened, while America emerged as the strongest power, engaged with the entire world.

Churchill must have been aware that at the least this was a possibility. He knew what most British people did not know: Britain could not afford to continue the war for long, let alone win it, without American economic help. It followed that continuing to resist Germany would mean sacrificing its economic independence and therefore, in the long run, its position as a world power. Although he fought hard against American encroachments, his gut reaction was to accept this rather than a Europe ruled by Nazi Germany. He belonged to an aristocratic class that laid great store by the commonality of values and principles between Britain and America. But most British people would have agreed with his choice.

One does not have to believe in the great man theory of history to see that the events of that summer turned on the decisions, predilections, viewpoints, and even personalities of three men: Churchill, Roosevelt, and Hitler. Hitler ruled Germany as a dictator as few men have ruled in modern times, deciding alone the issues of war and peace. Churchill ensured that Britain would fight on when the odds against it were overwhelming. Roosevelt guided American policy and American opinion, although not alone and not without a push from events at home and abroad.

This was one of those rare periods in which the importance of what was happening was starkly apparent at the time. It was clear to the British public, suffering under bombing and watching air battles in the skies above their cities. It was clear to President Roosevelt and those who were trying to alert that part of the American public that was not yet convinced that what was happening across the Atlantic should concern them. And it was clear to Winston Churchill.

In August 194 0, the king of Sweden suggested mediation between Britain and Nazi Germany. Foreign Office officials produced a carefully crafted reply, leaving options open, and sent it to Churchill for approval. Churchills comment was a private memo to an official, not intended for publication. He said the contents of the proposed reply appear to me to err in trying to be too clever, and to enter into refinements of policy unsuited to the tragic simplicity and grandeur of the times, and the issues at stake.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940»

Look at similar books to Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nineteen Weeks: America, Britain, and the Fateful Summer of 1940 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.