Rebecca Coleman

INSIDE THESE WALLS

My mother used to drive me to ballet lessons in her white Ford Torino, her delicate fingers light on the wheel, rolling slowly down the clean streets of San Jose as I sat beside her in my leotard and pink tights. Often the driver in front of us would glance in his mirror and slow down, mistaking us for a police car. Come on, sport, she would mutter under her breath, imitating my father, even long after he died. I found it comforting, the way she kept his presence alive in ephemeral but steady ways, and I felt as though he could still protect me. It was startling to discover that wasnt true, but for a while it gave me comfort.

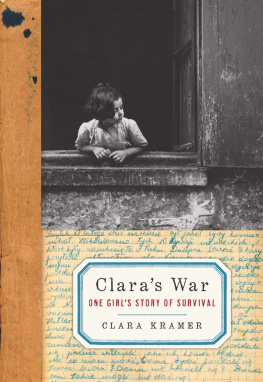

The lessons began when I was four, ended abruptly at age thirteen, and began again much later, when I was forty-three years old. At that age I practiced alone, without a mirror, without a real barre, because I had no choicebut the music was the same as ever, Beethoven and Brahms selections from Afternoon Classics on NPR. I am very, very good at going deep inside my mind and, even with my eyes open, imagining my surroundings as they should be rather than as they are. Sometimes, when I practice, I imagine myself as a six-year-old in the high-ceilinged studio with the long mirrored wall and the record player in one corner. Back then I was just Clara and my name meant nothing. I could even say the entire thing, Clara Mattingly, and no flicker of recognition or shock would pass through the gaze that rested on me. I remember how small and light my body felt then, a wonderful sealed machine, an egg. I remember the way the rain lashed the tall old windows, whipped the trees outside, but couldnt touch the airy sanctuary filled with piano music and the warmth of a dozen energetic small bodies. Other times I let myself be older, even my own age, which is forty-seven; I imagine I am dancing with a partner, a strong and muscular man with capable, gentle hands and an empty space where his face should be.

In the four years since I began to practice again, I cherish what the work has done to my body. Though I dont have pointe shoes, the muscles in my legs are strong and lean now. There is a dignity to the way my spine holds up my head and shoulders, which is very important, and when my feet rest against the earth, each toe feels like a separate soldier, ready to help me sprint in any direction. After everything my body has been throughchucked through the maze of my life, striking every wall and obstacle along the wayat last it feels like my own. Its evidence I wear outwardly that a person can change, she can grow stronger and better, carry herself taller. Even if no one else cares, I do. I care every day.

The orange tabby cat slips through the skinny gap low down below the razor wirea daily miracle. Her eyes lock with mine. I sink down to my haunches in the shadow of the guard tower and hold out the one-third slice of bologna Ive saved in the pocket of my uniform, folded into a paper napkin. She pads straight toward me, leaving little dust-prints across the yard. When she reaches me she examines it, sniffing curiously like a connoisseur before nibbling. Only after she accepts it do I begin to pet her, one questioning pat first, then big, long, affectionate strokes down her back. Oh, yes, what a girl, what a girl, I say in my grandmother voice. She arches and purrs, and I am pleased. I never take anything I havent earned.

Her name is Clementine. I named her for the color of her fur, although I used to have a kitten by the same name who was gray and white, back before. The other prisoners call her Frankfurter, and I dont know why. But Ive long since stopped caring why they do what they do. They leave me alone because of who my cellmate is, and thats all the truce I need.

The new guard is watching me. She is some distance off, in the haze of the midday heat, and her gaze is frank and bare. I know what she is thinking: that I dont look the way she expected. Not like the actress who played me in the movie, and not even like my own old photographs. In all of those, the smeary newsprint ones from more than two decades ago, my hair is in a sort of blonde pixie cut, but with long, smooth bangs. It was 1984, after all, and back then you either wore it long and feathered at the sides or you cut it short if you wanted to be taken seriously at the office. Now I dont really worry about how Im perceived around the office, so I just tie it back into a ponytail and have them chop it above my shoulders when it gets too difficult to comb. And there are other differences, too. When those photos were taken, I didnt need glasses yet. I hadnt yet had a baby, so my hips were still those of a young girl. I was twenty-three, and though I wasnt exactly a wide-eyed naif, expressions still tended to pop onto my face like some sort of cartoon character. You unlearn that after a while, here. You learn instead to keep it flat.

Clementine finishes the bologna, and I rise up from my crouch, feeling it a little bit in my knees. The sun is harsh and direct. This is Imperial County, where California bumps up against Arizona and Mexico, creating a great flat expanse of land offered up to the sun like one of those mirrored tanning reflectors my mother used to bring with her to the pool. I didnt grow up here. My family lived in San Jose, far to the north. But this is where Ill be buried, over in the gated-off part of the yard with the aged felons and the suicides, the stillborn babies and all the unclaimed.

The buzzer sounds, and we form up to return to our cells for the hour until dinner. And then theres a nice surprise. A letter. I know who its from without looking at the return address and slip it from the already-torn envelope.

Dear Clara,

Well I am a grandfather now. Doesnt that make me feel old. Ha, ha. My daughter had her baby. They named him Keith Robert Davidson Jr. I went to see him and he is good.

On Friday I went to the dragway to see the race. Spencer Massey signed my program. It was a lot of fun and I promise I didnt drink too much afterward, only two.

Well, I guess thats all. How are things there? How is your job making books for the blind people? I saw a blind girl with a cane at Walmart and I wanted to ask if she has any of those books and tell her I know the lady what makes them. But I was afraid I would scare her just being a strange person talking to her out of nowhere what she cant see. So I did not ask her.

All my love,Emory Pugh Jr.

P.S. ONE DAY AT A TIME

I smile, fold the letter along its creases and slide it back into the envelope. His letter from last week is on my shelf; I replace it with this one and throw the earlier one into the garbage. This is how it is here, living in the sweep of a single turn of the earth, never letting the evidence mount that time passes. For those with a release date, all their existence is in counting down the days, the hundreds or thousands, between now and then. For me there is only one day, and I live it over and over and over.

* * *

I used to work on braille transcriptions of textbooks every day, but now I mostly do the tactile drawings, which are raised versions of the maps and diagrams. Its very specialized work. At the Braille shop I line up my instruments on the desk: foil, leather punch, tracing wheel, paper tortillion and a canister of toothpicks. Im fortunate that they trust me with these tools, given what I did. But I had already been in for eight years when I began the Braille training, and at first it was only with the typewriter. So I earned it over time.

One of the guards, Officer Kerns, sidles up near me. Morning, ballerina girl, she says. Its more jeering than fond, and Id rather if she just called me by my number. Hows your friend Emory?

Hes getting along. Theres no need for her to ask me. They read my mail and discuss it amongst themselves.