Ibrahim al-Koni

New Waw, Saharan Oasis

Ababa: a member of the Council of Nobles

Aggulli: a sage and leader

Ahallum the Hero: the tribes warrior

Amasis the Younger: a noble elder

Asaruf: a noble elder

Diviner or Soothsayer: the leaders confidant

Ejabbaran: noble elder, sage

Emmamma: a noble elder, eventually the oldest man in the tribe and its venerable elder

Enigmatic Stranger: Wantahet or one of his avatars

Excavator: a stranger who travels with the tribe and digs his tent in the belly of the earth

Imaswan Wandarran: spokesman for the Council of Nobles

Leader: a poet in love with a female poet but condemned to lead a Tuareg tribe

Lover of Stones: the tribes master builder

Virgin, Tomb Maiden, Temple Maiden, Priestess: the Leaders posthumous bride and his medium

Wantahet: a figure from Tuareg folklore

In an interview with Scott Simon on National Public Radio, the Appalachian author Ron Rash said: Landscape is very often destiny for a writer and referred to literature of landscape.1 The landscape of the Sahara Desert has certainly been destiny for Ibrahim al-Koni, and his novel New Waw: Saharan Oasis contrasts the landscapes and cultures of desert nomadism with those of oasis life.

Al-Koni has written that, from the time of his descent from the high desert plateaus to start his formal schooling at twelve, he has felt a mission to speak for the desert, to help it make its own statement, which had not yet been enunciated. Melville had spoken for the sea, Dostoyevsky for the city, and Antoine de Saint-Exupry had even spoken for space. Only the desert has not yet offered its statement. So, when he began to write in the mid 1960s, what was essential was to express the desert. At the same time, though, he points out that Every reader of my works quickly perceives that the desert I am talking about is a metaphor for the world, an allegory for the world.2

Ibrahim al-Koni, a Tuareg whose mother tongue is Tamasheq, is an international author with many identities. He is an award-winning Arabic-language novelist who has already published more than seventy volumes, a Moscow-educated visionary who sees an inevitable interface between myth and contemporary life, an environmentalist, and a Saharan writer who depicts desert life with great accuracy and emotional depth while layering it with mythical and literary references the way a painter might apply luminous washes to a canvas.

His elegant, formal Arabic can be complex and suggests a clear and simple but still formal English rendition, with an occasional modern word added to rouse the reader from any mythical slumber. The description in New Waw of the excavators love affair with the earth in the original Arabic is a virtuoso piece of lyrical Arabic prose. Chapter XII contains a memorable landscape painted with words. In a chapter devoted to al-Konis work, Ziad Elmarsafy has described his language as highly stylized Arabic.3

Ibrahim al-Konis political fiction is philosophical, and readers occasionally remark that some of his novels, like New Waw, are intellectually challenging at several levels of meaning. There are a number of words that al-Koni has used systematically in multiple novels till they have become technical terms. These include words like al-khafa or Spirit World, al-khala or the wasteland, al-arraf (feminine: al-arrafa) for diviner, and al-tih for the deserts labyrinth.

Al-Koni does not simply take his readers on an adventurous trip through the Sahara but embeds them in a culture in which the natural world is rife with signs, symbols, sparks of enlightenment, and prophecies. A senile bird is a sign. When the migratory birds leave the nomads encampment, diviners follow the flocks to search for the prophecy encoded in their trajectories. The master mason explains to the diviner in New Waw that We have a duty to discover the symbol in everything.

The Tuareg, or Kel Tamasheq, are a traditionally pastoralist, nomadic Berber people, who have moved freely across the Sahara from Libya, Tunisia, Algeria to Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Today national boundaries and policies hinder their migrations, and there have been armed Tuareg insurrections in Mali and Niger. In April 2012, an independent state of Azawad was proclaimed in three northern districts of Mali Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu by Tuareg rebels reinforced by arms from Libya. In January 2013 France led an offensive to retake the north of Mali from the Islamists who had pushed aside their Tuareg allies.

The Tuareg language is Tamasheq (also known as Tamahaq), which has its own alphabet, Tifinagh, that dates back at least to the third century BCE. Evidence of Arabic-Tamasheq bilingualism among the Tuareg in Mali goes back hundreds of years in the form of inscriptions and graffiti.4 Currently there is at least one other Tuareg novelist writing in Arabic: Umar al-Ansari.5

The Tuareg have been affiliated with Islam for centuries, but the goddess Tanit is invoked several times in New Waw and traditional Tuareg life has been governed by a tribal code of law, even though its written text is no longer extant. In his novels al-Koni refers to this lost law as al-Namus, perhaps to distinguish it from the Islamic Shariah.

The oasis novels by al-Koni trace the development, flourishing, and destruction of an oasis community named in honor of the Tuareg peoples lost oasis, the paradise-like Waw (pronounced approximately like the English word wow). This distant oasis lying beyond every other oasis still occasionally appears to a few visionaries who are not looking for it. Al-Koni, who welcomes multiple allusions, has also referred to it as another Atlantis.6

New Waw (Waw al-Sughra, 1997, more literally Little Waw or Lesser Waw) is the first book in a trilogy that continues with The Puppet (al-Dumya, 1998) and The Scarecrow (al-Fazzaa, 1998). A putative fourth volume is The Tumor (al-Waram, 2008), although these books have been published and marketed separately in Arabic.

New Waw describes the birth and growth of this oasis in the Sahara, and major characters like the venerable elder Emmamma, the warrior Ahallum, and the sage Aggulli (also Aghulli) are introduced here. The Puppet chronicles the communitys peak of prosperity and therefore also the beginning of its decline. The eponymous character of The Scarecrow may appear in one or more guises in New Waw and is an enigmatic, apparently benign character in The Puppet. Finally in The Scarecrow this avatar of the Tuareg mythic figure Wantahet supervises the destruction of New Waw, reveling in his self-righteous sadism. When the oasis is under siege from international forces, he masterminds the killing of its inhabitants and then morphs back into the scarecrow.

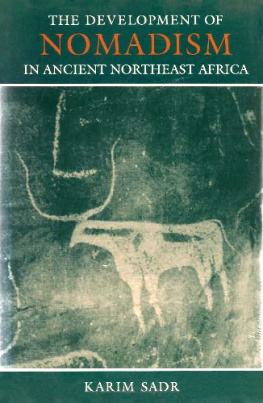

From a nomadic point of view, any settlement even for pressing reasons of leadership succession and even in a model oasis community like New Waw is subversive and a disruption of the traditional nomadic ethos, according to which endless migration provides a geographical cure.7

In West Africa, Islamic societies have retained elements of pre-Islamic cultures for extended periods, and Sufism has been an important strand in the Islamic tapestry there. Tuareg spirituality as depicted in al-Konis fiction is also multifaceted. The inhabitants of the Spirit World, many of whom are jinn (genies), maintain an uneasy truce with their Tuareg neighbors. (As in other parts of Islamic West Africa, in Tuareg lands the jinn recall earlier folk gods.) Like the author, al-Konis heroes typically feel a special bond with their ancient ancestors and the Saharan rock inscriptions they left behind. In novels like