TRANSLATORS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Lily Pond, editor of Yellow Silk, who introduced us and published the first fruits of this project; Michael Katz, our agent and unofficial third partner; Charles Levine, for his early support and encouragement; Kaz Tanahashi, for his generosity in reviewing the appendix; and Luann Walther, our Vintage editor. Jane Hirshfield would also like to thank Karen Brazell, whose courses introduced her to the poets translated here, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, for their support of her work during the year this project was begun.

Appendix

Selected Bibliography

ANTHOLOGIES OF JAPANESE LITERATURE

Keene, Donald. Anthology of Japanese Literature. New York: Grove Press, 1955.

. Twenty Plays of the N Theatre. New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1970. Contains Komachi and the Hundred Nights and Komachi at Sekidera.

Rexroth, Kenneth. One Hundred Poems from the Japanese. New York: New Directions, 1955.

. One Hundred More Poems from the Japanese. New York: New Directions, 1976.

Rexroth, Kenneth, with Ikiko Atsumi. The Burning Heart: Women Poets of Japan. New York: Seabury Press, 1977.

Sato, Hiroaki, and Burton Watson. From the Country of Eight Islands. New York: Doubleday, 1981.

Waley, Arthur. Japanese Poetry: The Uta. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1976.

. The N Plays of Japan. New York: Grove Press, n.d. Contains Sotoba Komachi.

ADDITIONAL READING FROM THE HEIAN ERA

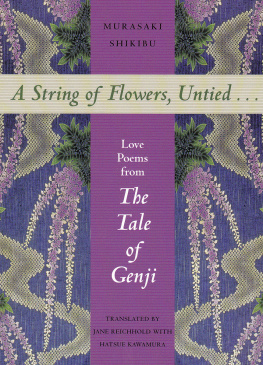

Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji, translated by Arthur Waley. New York: Random House, Modern Library, 1960.

. The Tale of Genji, abridged version, translated by Edward Seidensticker. New York: Random House Inc., Vintage Books, 1990.

Kokinsh: A Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern, translated and annotated by Laurel Rasplica Rodd with Mary Catherine Henkenius. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Kokin Wakash: The First Imperial Anthology of Japanese Poetry, translated by Helen Craig McCullough. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985.

Izumi Shikibu. The Izumi Shikibu Diary, translated and with an introduction by Edwin A. Cranston. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969. Invaluable for those who wish to know more about Izumi Shikibu.

Miner, Earl. Japanese Poetic Diaries. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969. Includes The Diary of Izumi Shikibu and another Heian-era diary, Ki no Tsurayukis Tosa Diary, as well as two later diaries.

Also see the anthologies listed in the previous section, particularly for poems by later Heian-era writers (the Kokinsh dates from quite near the beginning of the period); for other works of prose by women writers of the court, such as excerpts from Murasaki Shikibus Diary and Sei Shnagons Pillow Book; and for translations of several N plays based on legends about Ono no Komachi.

FOR FURTHER READING ON HEIAN-ERA POETRY AND CULTURE

Brower, Robert, and Earl Miner. Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961. Definitive.

Kato, Shuichi. A History of Japanese Literature, The First Thousand Years, translated by David Chibett. New York: Kodansha International, 1981.

Miner, Earl. An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1968. An abbreviated version of Brower and Miner, Japanese Court Poetry.

Morris, Ivan. The World of the Shining Prince. New York: Peregrine Books, 1979. A treasure trove of information about life in the Heian court.

Tsunoda, Ryusaku, William Theodore de Bary, and Donald Keene. Sources of Japanese Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1958.

FURTHER READING

Aitken, Robert. A Zen Wave: Bashs Haiku and Zen. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1978. Although the subject matter of this book, the haiku of the seventeenth-century poet Bash and how it reflects the mind of Zen Buddhism, dates from many centuries after the Heian period, no volume intended for the general reader provides a better introduction to both the linguistic texture of Japanese poetic diction and the close reading of Japanese poetry. The book can also serve as an excellent, if somewhat unusual, introduction to Buddhist thought.

LaFleur, William R. The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983.

On Japanese Poetry and the Process of Translation

For those who may wish to know a bit more about Japanese poetry and the language in which these poems were written, this appendix provides a brief introduction, as well as a few examples of the process underlying the translation. In addition, the curious can turn to the notes to individual poems, which include the romaji (the Japanese text written in roman alphabet) for each poem, offer specific background information when it might be of interest, point out the use of certain technical devices, and, occasionally, expand on a poems meaning or highlight its technique.

Of the many differences between the language in which these poems were composed and that into which they have come, one of the most significant is that Heian-era Japanese (and present-day Japanese) is a highly inflected language. This means that grammatical constructions are often contained within the words themselves, usually in their endings, as in Latin; when an auxiliary word is used, it generally follows rather than precedes its companion. English, by comparison, is a partially inflected language; although some information is given in word endingsfor example, the distinction between singular and pluralword order also greatly determines grammar. The man ate the lion means something quite different from the lion ate the man.

Because of the conventions of ordering in English grammar, the understanding of a sentence tends to develop from beginning to end, and when auxiliary words are used (I will have left by then), they generally precede the part of speech they modify. For novice readers of Japanese, the order in which a poems information unfolds, both within phrases and over the course of the poem, at first often seems reversed. Again, anyone who has studied Latin or another inflected language knows how quickly one learns to take ones cues as they come; but until the originals order begins to seem natural, reading the phrases backwards word by word or starting the poem from its end will usually help in untangling the meaning. (An additional source of potential confusion is the fact that the language of the Heian era differs more greatly from contemporary Japanese than that of Chaucer from contemporary English, and some of the words in these poems were archaic even at the time of composition.)

Differences in linguistic structure between English and Japanese also affect sound qualities, both within words and in the way sound functions in poetry. It is not at all unusual, for example, for a Japanese word to occupy seven syllables; onomatopoeia, an exceptionally many-syllabled word for English, has only six syllables. Also, the fact that all words in Japanese end with one of a relatively small number of vowels (plus the occasional word ending with n, which is counted as a syllable and derives from the older mu) precludes the use of rhyme as it is employed in other languages: only a large variety of possible end-sounds allows their duplication to become a source of ingenuity and surprise, and, hence, aesthetic pleasure.

Several other important differences between the two languages are worth noting. A Japanese poet may choose to specify a pronoun, verb tense, or whether a noun is singular or plural, but very often such information is not given; in Japanese, nouns are not accompanied by modifying articles such as