Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

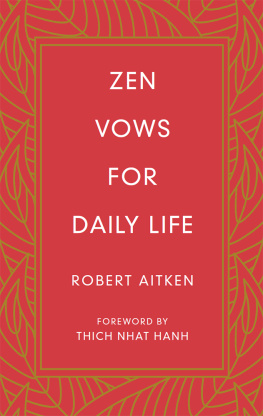

To my Zen master, Yamada Kun Rshi,

who shows me Right Action,

and to Diamond Sangha students

who help me do it.

Most of these essays appeared in earlier forms in Blind Donkey, and all appeared in Mind Moon Circle. Kahawai: Journal of Women and Zen published Not Killing, as did Impulse. The Middle Way and Ten Directions both published Not Stealing. Gandhi, Dgen, and Deep Ecology appeared in Zero and in Simply Living, and is anthologized in Deep Ecology, edited by Bill Devall and George Sesshins, Gibbs M. Smith, Inc.

Benjamin Lynn Olson transcribed the first talks I gave on the precepts in 1976, and suggested that I make them into a book. His transcriptions were very useful to me in the course of revisions I made in the talks over the years, and I am very grateful to him for his help and encouragement.

Many people have read the manuscript and made useful suggestions for revision. First and foremost among these is Wendell Berry, whose wise and incisive comments prompted me to make important changes. Stephen Mitchell marked up every essay before its publication in Blind Donkey and rereading the work now I can see his influence on almost every page. P. Nelson Foster edited the essays for Blind Donkey and helped me very much with formulating my points in logical sequence.

I must also acknowledge the assistance of Anne Aitken, Teresa Vast, Gary Snyder, Michael Kieran, John Tarrant, and others who read all or portions of the manuscript and made helpful comments. I bow to my typists as well: Sarah Bender, Victoria Chau, Diane Epstein, and Stephenie LHeureux.

Kazuaki Tanahashi made the calligraphy Tadashii (Upright) for the title page of the book, and I thank him for his creative, generous gift. Finally I want to thank the staff of North Point Press: Jack Shoemaker, Tom Christensen, Dave Bullen, and the others, who turn manuscripts into books with genius and dispatch.

I see nobody on the road, said Alice.

I only wish I had such eyes, the King remarked in a fretful tone. To be able to see Nobody! And at that distance too!

Lewis Carroll

Through the Looking-Glass

Each time the wave breaks

The raven

Gives a little jump.

Nissha

(Translated by R. H. Blyth,

Senry: Japanese Satirical Verses )

The precepts of Zen Buddhism derive from the rules that governed the Sangha, or community of monks and nuns who gathered about kyamuni Buddha. As the religion of Buddhism developed through the Mahayana schools, the meaning of sangha broadened to include all beings, not just monks and nuns, and not just human beings. Community continues to be a treasure of the religion today, and the precepts continue to be a guide. My purpose in this book is to clarify them for Western students of Buddhism as a way to help make Buddhism a daily practice.

Without the precepts as guidelines, Zen Buddhism tends to become a hobby, made to fit the needs of the ego. Selflessness, as taught in the Zen center, conflicts with the indulgence that is encouraged by society. The student is drawn back and forth, from outside to within the Zen center, tending to use the center as a sanctuary from the difficulties experienced in the world. In my view, the true Zen Buddhist center is not a mere sanctuary, but a source from which ethically motivated people move outward to engage in the larger community.

There are different sets of precepts, depending on the teachings of the various schools of Buddhism. In the Harada-Yasutani line of Zen, which derives from the St school, the Sixteen Bodhisattva Precepts are studied and followed. These begin with the Three Vows of Refuge:

I take refuge in the Buddha;

I take refuge in the Dharma;

I take refuge in the Sangha.

Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha can be understood here to mean realization, truth, and harmony. These Three Vows of Refuge are central to the ceremony of initiation to Buddhism in all of its schools.

The way of applying these vows in daily life is presented in The Three Pure Precepts, which derive from a gth (didactic verse) in the Dhammapada and other early Buddhist books:

Renounce all evil;

practice all good;

keep your mind pure

thus all the Buddhas taught.

In Mahayana Buddhism, these lines underwent a change reflecting a shift from the ideal of personal perfection to the ideal of oneness with all beings. The last line was dropped, and the third rewritten:

Renounce all evil;

practice all good;

save the many beings.

These simple moral injunctions are then explicated in detail in The Ten Grave Precepts, Not Killing, Not Stealing, Not Misusing Sex, and so on, which are discussed in the next ten chapters.

These sixteen Bodhisattva precepts are accepted by the Zen student in the ceremony called Jukai (Receiving the Precepts), in which the student acknowledges the guidance of the Buddha. They are studied privately with the rshi, the teacher, but are not taken up in teish (Dharma talks), or discussed at any length in Zen commentaries.

I think the reason for this esotericism is the fear of misunderstanding. When Bodhidharma says that in self-nature there is no thought of killing, as he does in his comment on the First Grave Precept, this was his way of saving all beings. When Dgen Kigen Zenji says that you should forget yourself, as he does throughout his writing, this was his way of teaching openness to the mind of the universe. However, it seems that teachers worry that no thought of killing and forgetting the self could be misunderstood to mean that one has license to do anything, so long as one does it forgetfully.

I agree that the pure words of Bodhidharma and Dogen Zenji can be misunderstood, but for this very reason I think it is the responsibility of Zen teachers to interpret them correctly. Takuan Sh Zenji fails to live up to this responsibility, it seems to me, in his instructions to a samurai:

The uplifted sword has no will of its own, it is all of emptiness. It is like a flash of lightning. The man who is about to be struck down is also of emptiness, as is the one who wields the sword.

Do not get your mind stopped with the sword you raise; forget about what you are doing, and strike the enemy. Do not keep your mind on the person before you. They are all of emptiness, but beware of your mind being caught in emptiness.

The Devil quotes scripture, and Mra, the incarnation of ignorance, can quote the Abhidharma. The fallacy of the Way of the Samurai is similar to the fallacy of the Code of the Crusader. Both distort what should be a universal view into an argument for partisan warfare. The catholic charity of the Holy See did not include people it called pagans. The vow of Takuan Zenji to save all beings did not encompass the one he called the enemy.

This is very different from the celebrated koan of Nan-chan killing the cat:

The Priest Nan-chuan found monks of the Eastern and Western halls arguing about a cat. He held up the cat and said, Everyone! If you can say something, I will spare this cat. If you cant say anything, I will cut off its head. No one could say anything, so Nansen cut the cat into two.

![Ben Aitken [Ben Aitken] - A Chip Shop in PoznaЕ„](/uploads/posts/book/140582/thumbs/ben-aitken-ben-aitken-a-chip-shop-in-poznae.jpg)