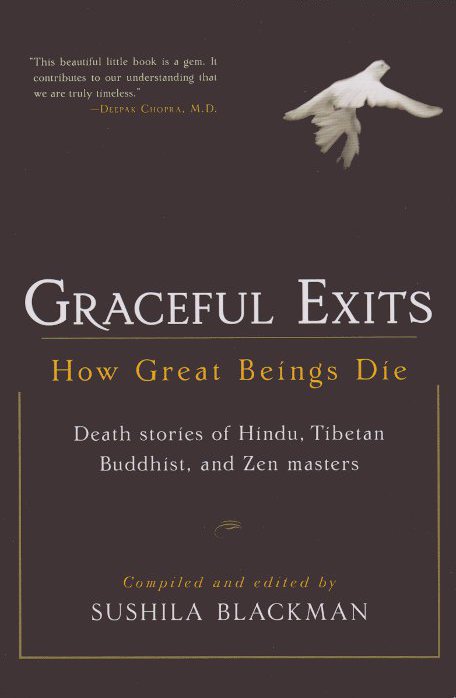

GRACEFUL

EXITS

How Great Beings Die

DEATH STORIES OF HINDU, TIBETAN BUDDHIST, AND ZEN MASTERS

Compiled and edited by Sushila Blackman

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2011

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1997 by Joseph K. Blackman, trustee for the Blackman Revocable Trust

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Graceful exits: how great beings die/compiled and edited by Sushila Blackman.

1st. Shambhala ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Weatherhill, 1997.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2416-4

ISBN 978-1-59030-270-5 (pbk: alk. paper)

1. DeathReligious aspectsBuddhism. 2. DeathReligious aspectsHinduism. 3. BuddhismDoctrines. 4. HinduismDoctrines. I. Blackman, Sushila.

BQ4487.G43 2005

294.3423dc22

2004065379

To Bhagawan Nityananda, Baba Muktananda, and Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, the living embodiment of the Siddha lineage.

INTRODUCTION

In that marvelous Indian epic poem, the Mahabharata, the sage Yudhisthira is asked: Of all things in life, what is the most amazing? Yudhisthira answers: That a man, seeing others die all around him, never thinks that he will die.

Two thousand years later, people still circumambulate the reality of their own death. In a recent New York Times article, infectious disease specialist Dr. Jack B. Weissman remarked, What strikes me about our system is that more people are afraid of how they are going to die than the fact that they are going to die. When we do think of dying, we are more often concerned with how to avoid the pain and suffering that may accompany our death than we are with really confronting the meaning of death and how to approach it. We are in dire need of role models, people to show us how to face leaving this world gracefully and to place death in its proper perspective. For this it is natural to turn to those most experienced in dealing with death (and with life): spiritual masters.

The Tibetan Buddhist, Zen Buddhist, and Hindu or Yogic traditions that are the focus of this book are deeply linked. One of these links is the extraordinary importance they place on the act of dying. To understand why, we need look no further than the principles of karma and reincarnation, which have been intricately woven into the fabric of life in the East since ancient times.

KARMA AND REBIRTH

According to the law of karma, all beings experience the consequences of their actionsboth mental and physical. The myriad desires and fears of each lifetime compel us to keep returning to earthly life to experience the fruits of our previous actions, whether bitter or sweet. Just as we bring the impressions from our waking life into our dreams, so the residual impressions of our actions in this lifetime accompany us to the next. The kind of life we come back into is determined, in large part, by how we live our present life. The masters from the East maintain that to live righteously, let alone to die well, one must act without any personal attachment to ones actions. To be delivered from the fear of death and the certainty of rebirth, one must act without desire, without a personal agenda, and without attachment to results.

Hindus maintain that until the individual soul (jiva) merges with the Absolute, the Self of all, it continues to be reborn. The Buddha also endorsed the traditional Indian view that humans are trapped in an endless cycle of lives, known as samsara, characterized by dukkha, or suffering. According to his teachings, there is no easy escape from this fate because our karmathe consequences of our actionssurvives the death of the body to condition a new physical existence. The Buddha did not teach that the individual is reborn; he insisted that all things are subject to the law of mutability or impermanence (known in Buddhism as anicca) and that there is no such thing as a personal identity or soul, a doctrine known as anatta or no-self. However, karmawhich can be understood as a package of energy containing both negative and positive chargesis transferrable from one life to the next.

Belief in reincarnation and the cycle of rebirth is not unique to the Buddhists and Hindus. For example, an ancient Egyptian hermetic text fragment states that the soul passes from form to form, and the mansions of her pilgrimages are manifold. There is also at least one passage in the Bible that suggests Jesus may have believed in reincarnation. In Matthew 17:13, Christ reveals his divine form to his three closest disciples, and then tells them that his precursor, John the Baptist, is actually an incarnation of the prophet Elijah. Origen, a prominent patriarch of the early Christian church, described rebirth in his De Principiis:

The soul has neither beginning nor end... Every soul comes to this world strengthened by the victories or weakened by the defeats of its previous life. Its place in this world as a vessel appointed to honor or dishonor is determined by its previous merits.

Thus the early Christians, like their master, appear to have accepted reincarnation, but the concept was suppressed by the Emperor Justinians Council of Constantinople in 538 AD. In the Jewish mystical tradition of the Middle Ages, the notion of a preexisting soul developed over time into the idea of reincarnation. According to David Chidester in his book Patterns of Transcendence, the Kabbalistic concept of gilgul (metempsychosis) came to signify a process whereby souls were continuously reborn untilthrough meditation, prayer, and conscientious ritual observancethey were purified of all sin and eventually restored to God.

Recently documented incidents also point toward the authenticity of reincarnation: children returning to cities where they lived in previous lives and identifying family members; the selection of tulkus (reincarnated lamas) from a written list of attributes left by the previous incarnation; and the spontaneous past-life regression experiences of many patients while under hypnosis by medical doctors, such as those Dr. Brian Weiss recounts in his book Many Lives, Many Masters. Such data are eroding the objections of even hardened skeptics and nudging us to revamp our understanding of who we are. As Stephen Levine so marvelously puts it in his book Who Dies? it is time for us to perceive ourselves as spiritual beings with physical experiences rather than as physical beings with spiritual experiences. This is how great beings perceive themselves, and how, to our great fortune, they perceive us as well.

THE PINNACLE OF HUMAN LIFE

KARMA AND REBIRTH

KARMA AND REBIRTH