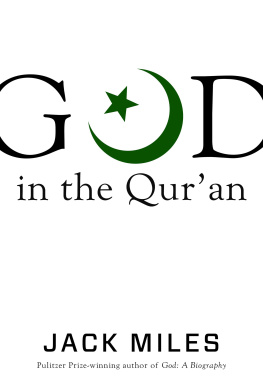

Also by Jack Miles

God: A Biography

Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God

A S EDITOR

The Norton Anthology of World Religions

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A . KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by Jack Miles

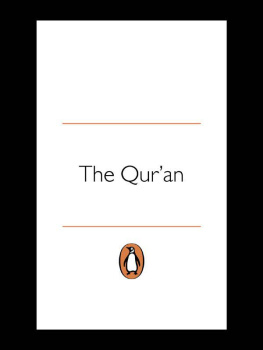

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

D E G RUYTER M OUTON : Excerpt from On Understanding Islam by Wilfred C. Smith, copyright 1981 by Mouton Publishers. Reprinted by permission of De Gruyter Mouton. D AN OB RIEN : Excerpt of Gods Brother by Dan OBrien, originally published in Scarsdale by Measure Press Inc., Evansville, Indiana, in 2015. Reprinted by permission of Dan OBrien. O NE w ORLD P UBLICATIONS , C / O PLSC LEAR : Excerpt from Sufism: A Beginners Guide by William C. Chittick, copyright 2000 by William C. Chittick. Reprinted by permission of Oneworld Publications, c/o PLSClear. W. W. N ORTON & C OMPANY , I NC .: Excerpt of It Is Enough to Enter from Pitch: Poems by Todd Boss. Copyright 2012 by Todd Boss. Reprinted by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miles, Jack, 1942 author.

Title: God in Quran / Jack Miles

Description: New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018005105 | ISBN 9780307269577 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525521617 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : God (Islam) | QuranCriticism, interpretation, etc.

Classification: LCC BP 134. G 6 M 55 2019 | DDC 297.2/11dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018005105

Ebook ISBN9780525521617

Cover photograph by Louis Pescevic

Cover design by John Vorhees

v5.4

ep

For Catherine

One who has lived many years in a city, as soon as he goes to sleep,

Beholds another city full of good and evil, and his own city vanishes from his mind.

He does not say to himself, This is a new city: I am a stranger here.

Nay, he thinks he has always lived in this city and was born and bred in it.

Rumi

Contents

Foreword

Of God, Religion, and the Violence of Sacred Scripture

Among all the books that have been written about God, I myself have written two: one about God in Jewish scripture and another about God in Christian scripture. The book before youabout God in Muslim scripture, the Quranis the third in the series. I am a Christian, a practicing Episcopalian, but I approach God in all three of these books not directly but only through the respective scriptures of the three traditions. I write, moreover, not as a religious believer but only as a literary critic writing quite consciously for an audience crowded with unbelievers.

What this means is that I approach the scriptures not through belief but through a suspension of disbelief. Suspension of disbelief is a notion introduced into English literary criticism by the nineteenth-century poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge. It is by the temporary suspension of disbelief that any of us is able to let go and enjoy a novel, a film, or a television series like Game of Thrones on its own terms. When we go to the movies on a summer night and see a romantic comedy, we do not object as the film goes along that the lovers on screen are not real lovers but only two actors pretending to be in love. We disbelieve in their ultimate reality, of course, but for the duration of the film, we allow them to be real. We play along.

You can play along in the same way even when a literary character is divine. Not long ago, for a course I taught, I had occasion to re-read Homers Iliad, this time in the wonderful Robert Fagles translation. The Greek god Zeus is a major character in that epicthe greatest of the Olympian gods. I do not believe that Zeus exists, but for the duration of my reading, I willingly played along with Homer, allowing Zeus to shape the course of The Iliad as powerfully as he does.

As a Christian, by a kind of reversal, I can temporarily suspend my belief that the God of the Bible is indeed much more than a literary character and take him as no more than that for the duration of an exercise in literary appreciation. Just as I can go to St. Peters Basilica in Rome on a Sunday to worship and then go back on a Monday to study its art and architecture, so I can hear Christs Sermon on the Mount on Sunday as a part of my worship and then study it on Monday as relevant data about Christ as a literary character. The two exercises are different, deeply so, but they are not mutually exclusive and can be mutually stimulating.

Literary criticism, beginning in this way with the aesthetic experience of a work of literature, is different from literary history or historical criticism. Historical criticism is concerned with such questions as Who wrote this work? When did he write it? Why did he write it? For what audience did he write it? Or did she write it? Or they? Was it originally in the language in which we now read it? What sources did they draw on, if any, as they wrote it, or is it truly an original creation? Has it been revised over time? Is it in circulation in more than one form? If so, which form is best? Is it perhaps the redacted combination of more than one version of itself? What has been its reception over time? Has it been translated? Has it ever been suppressed?

And so forth. Such questionslegitimate as they are, fascinating as they can be, and endless as they also areare not the subject matter of this book. A scholar may have answered dozens of such questions about a given work of literature, indeed spent a lifetime answering them, without ever quite engaging the work in itself, as an aesthetic creation separable to some extent, as all great works are, from the time and place and circumstances in which it arose. Historical criticism need not interfere with literary appreciation, and the two can often be symbiotic, but the two are even then distinguishable.

In what follows, we will consider a cast of iconic characters who appear both in the Bible and in the Quran through an ongoing comparison whose focus at every point will be on God as the understood central character. Our modest goal will be a certain aesthetic appropriation not of the entire Bible or the entire Quran but just of these related passages within the two. My hope is that you will join me by whatever suspension of belief or disbelief works for you as I give primary consideration to Allah, God, as the overwhelmingly dominant central figure in the passages from the Quran.

Over the centuries, the view most often taken of the Quran by Jews and Christians alike has been the view classically taken by Jews of the New Testamentnamely, Whats true is not new, and whats new is not true. Non-Muslims have disbelieved and dismissed what Muslims believe of the Qurannamely, that it is Gods last word to mankind, the crown of revelation, restoring what Jews and Christians had lost from or suppressed in their scriptures by oblivion or corruption. My invitation here to Jews and Christians and the many others who disbelieve that bold Muslim claim is that, as a modest exercise in literary appreciation, they temporarily suspend their disbelief while together we attempt an engagement with God as the central character of the Quran, and with the Quran as an elusively powerful work of literature. My invitation to Muslims is that just as they might pray in a mosque on Friday but study its dome as students of architecture on a Tuesday, so they too might play along with this Tuesday exercise, this literary engagement with just a few selections from the Quran, read in conjunction with matching passages from the Bible. Honoring the Holy Quran in this way, as literature, is a way to open it, with sympathy, to new readers.