Table of Contents

For my mother, Bee

INTRODUCTION

2003.

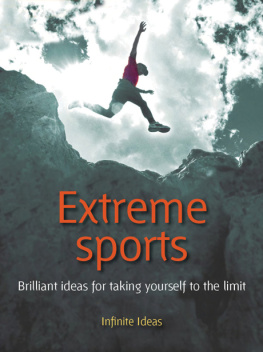

Opening night at the Banff Mountain Film Festival. We sit in a large, packed auditorium, watching fast-paced clips of people throwing themselves off high cliffs, kayaking over huge waterfalls, and skiing down precipitous mountain slopes. Crazy, seemingly impossible feats that bring cheers, whoops, and whistles from the crowd. My own pulse races, my palms sweat. What intrigues me is not just that these adventurers willingly go to the edge, but how at ease they seem there.

After the showing I seek out the Norwegian explorer Brge Ousland, a man who has made epic treks to the South and North poles, across Antarctica and the Patagonian Ice Cap. Completely unsupported. A man who has refused to stop at research stations, eschewing any warmth and company on his missions. Why does he undertake such journeys?

Because they strip me away, he says simply. I become like an animal. I find out who I really am.

Later that night, in my warm hotel room, I gaze through double-glazed windows at a snowy mountain face looming up from the Bow Valley. Somewhere on its slopes a man climbs in the dark. Alone. Earlier in the evening Id met him, a local in thearea, dressed in his climbing gear, backpack at his feet, having a quick drink in the bar before setting off. He had a simple happiness about him; he was relishing the prospect of a night on the icy slopes. At this very moment, he is moving upward, like an animal, vulnerable to the elements. I think about all the layers surrounding me, insulating me from everything he is experiencing. I know I couldnt do what he is doing, or what Brge Ousland does. Nor do I want to. But I envy them for being so at home in the wild world, wide open to its beauty, plugged into its power. For whatever it is they find there that proves so irresistible.

I was at the Banff festival to receive a prize for a book Id written about the personal costs of climbing. All of the climbers I had interviewed for that book described an overwhelming sense of aliveness they felt in the mountains, and at moments of great danger. To my surprise, many of them referred to this as a spiritual sensation, something I interpreted as entering a transcendence zone. Id been even more surprised when some of the climbers shared stories of the further reaches of this zone: encounters with ghosts and spirits, telepathic communications, precognitive dreams, astral travel, bouts of superhuman strength.

Extreme adventurers, of any ilk, must do more than just master the skills of their sport. Their survival depends on their maintaining a constant focus and paying close attention to all the forces of nature, becoming hyperaware of the slightest breeze, a change in temperature, the way snow feels under their boots or rock on their fingers. And when disaster hitsthe avalanche breaks loose, the parachute collapses, the boat overturnsin a split second they must throw together past experience with what is happening in the present, and react. Their lives depend upon this processwhat some psychologists call thin slicingof finding patterns in situations and behavior based on very narrow segments of experience. Its what most of us call intuition, a knowing without knowing.

Knowing without knowing. Was it possible, I now wondered, that as these adventurers tune into the natural world, they unwittingly open channels to hidden powers and realms of experience that we call mystical and paranormal? That these channels lie dormant in us all, shut down beneath layers of insulation? And that the process of risk-taking strips away that insulation, opening the way to spiritual transcendence?

These questions were the genesis of this book. My work on it began with another question: Is reaching a state of spiritual transcendence the fundamental lure of extreme adventure? Needless to say, the more I looked for answers, the more questions accumulated, but as the work progressed I became increasingly convinced that extreme adventurers break the boundaries of what is deemed physically possible by pushing beyond human consciousness into another realm. Their experiences give a glimpse of those unimagined levels of existence, signing the way for others to follow.

Before I set out to write this book, I was a fence-sitter about all things spiritual, mystical, and paranormal. What stopped me from settling firmly on the side of rationalism were memories of puzzling incidents in my lifea mystical awakening after I nearly drowned off the coast of Morocco; a premonition of my lovers death on Everest and the visitations I received from him after the news was confirmed; the spirit of a river that protected me from illness and banditry while I kayaked hundreds of miles down its course. At the time, Id rationalized each of these sensations as being the result of fear, worry, grief, or exhaustion. But listening to the stories of adventurers made me wonder if, perhaps, they were more than just products of my imagination.

I gathered accounts of spiritual, mystical, and paranormal experiences from an array of extreme adventurers: BASE jumpers, highliners, astronauts, solo sailors, freedivers, kayakers, surfers, big-mountain skiers and snowboarders, as well as mountaineers. I cross-checked their accounts against the research and opinions of scientists, psychologists, and spiritual teachers. This journey back and forth from wonder to science, mystery to explanation, is documented in these pages. It begins with my premise that reaching a spiritual state of being is the principal lure of extreme adventure, but that until there is a common language for this experience there will be no common acceptance of it. The next section of the book examines fear, suffering, and focus as components that enable adventurers to release hidden powers and access other realms of experiences; it also explores the possibility that a close connection to the natural world is a vital part of how adventurers access these realms. There follows a wealth of stories from adventurers about precognition, intuition, telepathy, and encounters with spirits, paranormal powers that I view through the lens of scientific opinion. The final chapters suggest that extreme adventure is not only a spiritual search, but also a spiritual tool. And that it is the same for all of us, adventurers or not. The hardest, most challenging experiences of our lives can enrich our existence, revealing our true identity, awakening us to a greater awareness of our own potential, and opening us to the infinite beauty of the universe.

PART ONE

The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science. He who knows it not and can no longer wonder, no longer feel amazement, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle.

ALBERT EINSTEIN, "The World As I See It

Chapter 1

SPIRITUAL ADDICTION

Across the table from me sits a woman whose idea of a pleasant Sunday afternoon outing is spidering up a frozen waterfall, attached only by the tips of her crampons and ice picks.

"The scariest thing for climbers, she says, "is having to look at why they climb.

"So, why do they climb? I ask.

For emotion, she says. For ego. For attention. Sometimes for excitement and money and fame. But mostly its about attaining spiritual heights.