Contents

About the Book

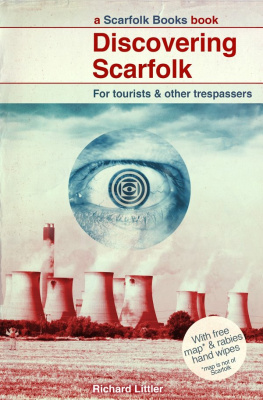

Scarfolk is a town in north-west England that did not progress beyond 1979. The entire decade of the 1970s loops ad infinitum. In Scarfolk children must not be seen OR heard, and everyone has to be in bed by 8 p.m. because they are perpetually running a slight fever

Part-comedy, part-horror, part-satire, Discovering Scarfolk is the surreal account of a family trapped in the town. Through public information posters, news reports, books, tourist brochures and other ephermera, we learn about the darker side of childhood, school and society in Scarfolk.

A massive cult hit online, Scarfolk re-creates with shiver-inducing accuracy and humour our most nightmarish childhood memories.

FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE RE-READ.

About the Author

Richard Littler is a graphic artist and screenwriter as well as a script consultant and occasional poet. He lives in Heidelberg, Germany.

Introduction

by Dr Ben Motte

(Editor, International Journal of Cultural Taxidermy)

The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there, so I wouldnt recommend it as a holiday destination.

J.K. Schaim (after L.P. Hartley)

THE BOOK YOU have in your hands contains a selection of archival materials pertaining to Scarfolk, a town in North West England, which is just west of northern England, though its precise location is unknown.

The archive is equally imprecise, unlike one methodically collated and carefully maintained by an official body such as a museum, notable persons estate, or child exchange farm. At first glance, one could dismiss the archives contents as a meandering assemblage of print ephemera from the 1970s but that would belittle its historical and cultural significance. The artefacts collected here permit us access to Britains recent social attitudes and mores, many of which we may be surprised to discover we had either forgotten or suppressed.

Before I discuss the artefacts sociological implications, I see it as my duty to bring to your attention how I came by the contents of this book. As a historian and academic, I eschew irrational notions so it is with some reluctance that I describe the circumstances as a mystery, an enigma that has consumed a substantial portion of my time.

Several months ago, I received in the post a large parcel wrapped in several sheets of reused brown paper. Enclosed was a 1970s tourist guide entitled Discovering Scarfolk. Many of the books pages are missing and the surviving ones are rubbed soft from frequent reading. The once slender volume is swollen to many times its original size and the spine, barely held together by layers of yellowing, brittle sticky tape, has deformed to accommodate numerous inserted documents and scraps: newspaper reports, public information literature, council documents, advertisements, book covers, product packaging, record sleeves, leaflets, till receipts for everyday products such as jam and magnetised crucifixion pyjamas and other print matter of varying size, shape and colour. Though I now refer to it as the archive, when I first laid eyes on this haphazard collection of papers I thought that it had been mistakenly diverted from its true destination: a paper recycling facility.

Only when I scrutinised the well-thumbed items did I discover that many were accompanied by often nonsensical annotations. For example, here is one of the first I encountered:

[] The many drinking straws protruding from the library walls are not art theyre for breathing has Mrs P imprisoned children in

As I read on, drawn in by the cryptic texts and images, I realised that I knew the author of these feverish commentaries. His name was Daniel Bush and he had been a fellow student when we read Telepathic Journalism at St Cheggers Pop Christ College, London, in the late 1960s.

If that was not unsettling enough, when only for the first time in 1970 editions.

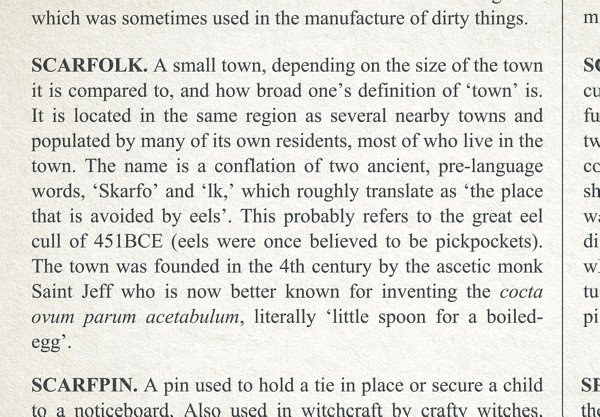

Apart from these nebulous snippets no other facts are included; no description of the towns precise co-ordinates, no detailed population figures or socio-economic details. In fact, I found no other verifiable reference to Scarfolks existence before 1970, nor any reference to it after 1979. However, there is an entry for a Scarefolke in the Domesday Book of 1086 CE . The details are meagre, cryptic, lists amount of plough land and taxable resources, among other details, but the Scarefolke entry simply reads:

[] In the name of William of England, the Lord God, and the fucking [illegible word. Looks like pineapple], and for the benefit of all, let no good man attend this land for fear of the unholy Ritel from Old English by J. Scud, an old English translator.]

There is no way of ascertaining if this is indeed the same Scarfolk. The only thing we can rely on for sure is Daniel Bushs Scarfolk archive still the only tangible testimony to the towns existence. Yes, I insist on the use of the word tangible. Can one man really have forged all these documents and within them an internally consistent town with distinct people, working businesses, schools, social clubs, not to mention rife but unhealthy attitudes towards race, gender, children and synchronised swimmers?

However, accepting the credibility of Daniel Bushs archive is a disturbing prospect. If we entertain the notion that Scarfolk is real, we are faced with innumerable implications.

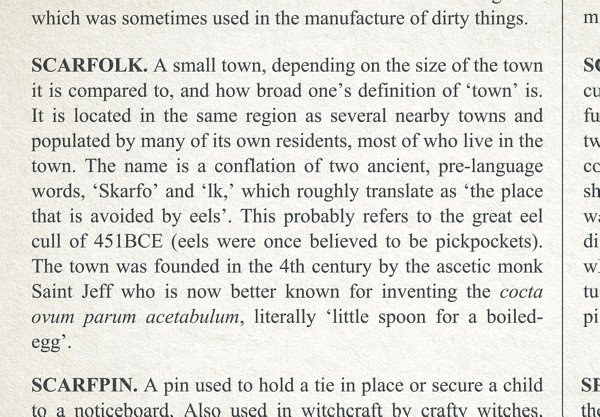

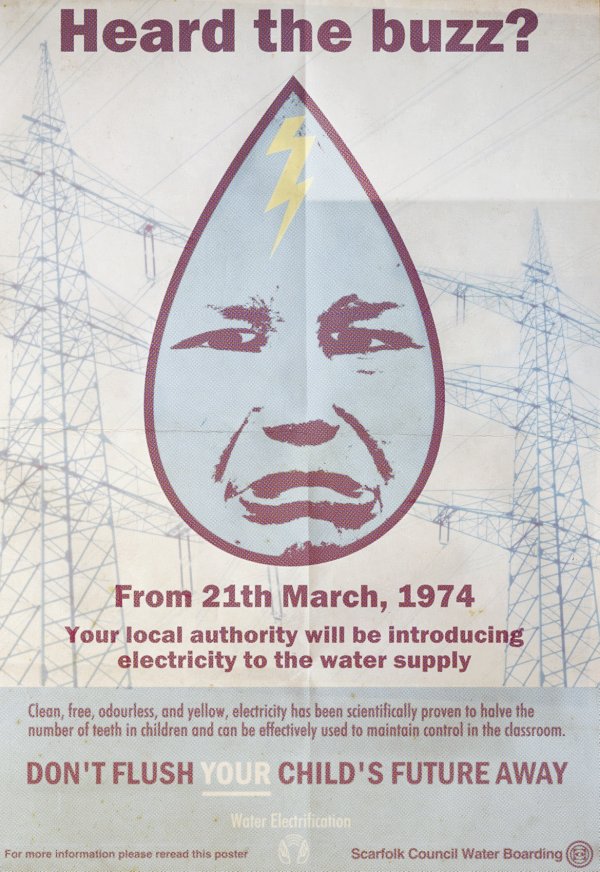

Did we really permit the electrification of Did we really monitor the very thoughts of our own citizens? Finally, could these once acceptable but now disdained ideals still be a part of our cultural DNA?

A poster preparing citizens for the imminent electrification of the water supply.

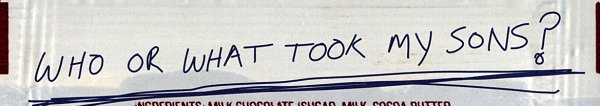

The archive addresses more than just social conventions. It is also a highly personal one that, like Theseuss twine, guides the reader around a labyrinth, and somewhere in that maze is the answer to a question that one man obsessively fought to answer for many years:

In this volume I have attempted to order Daniel Bushs archive and hopefully convey to you as succinctly as possible what I feel he was trying to communicate. I am aware that I could have approached the material in numerous ways, but I hope I have chosen the most scholarly. As difficult as it may be, I recommend you do the same as you enter the world of Daniel Bush and discover Scarfolk for yourself.

Dr Ben Motte (6.6.19446.6.2014)

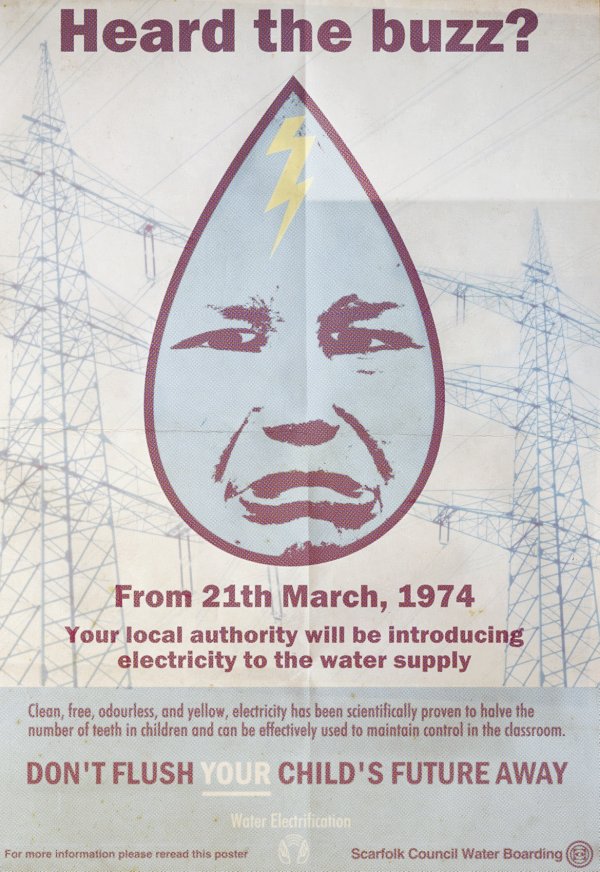

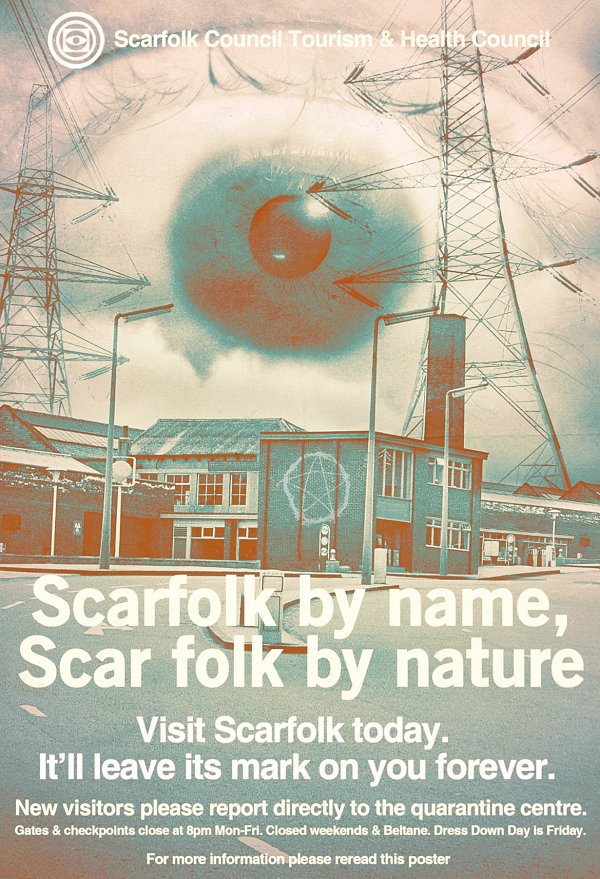

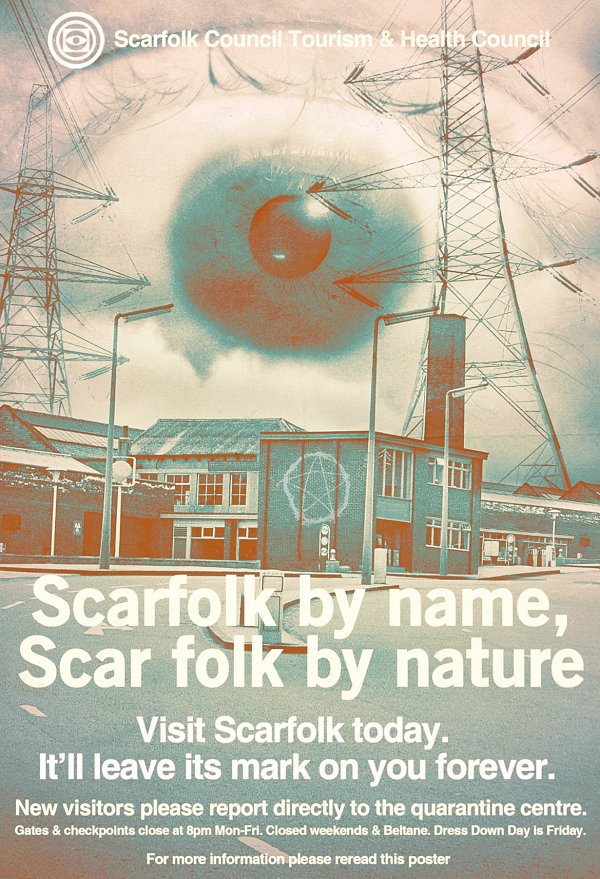

A Scarfolk tourism poster, 1972.

Disappearance Day

DESPITE THE CHAOS of Daniels archive, one thing is clear: it points to the events of 23 December 1970, which is when Daniel and his two young twins, Joe and Oliver, planned to move house.

A poster preparing citizens for the imminent electrification of the water supply.

A poster preparing citizens for the imminent electrification of the water supply.

A Scarfolk tourism poster, 1972.

A Scarfolk tourism poster, 1972.