About the Author

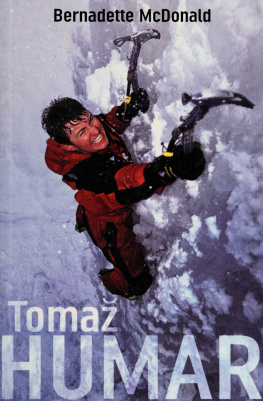

Bernadette McDonalds biography of Elizabeth Hawley, Ill Call You in Kathmandu, was published in 2005. For many years she was Vice-President, Mountain Culture at The Banff Center and Director of The Banff Mountain Film and Book Festivals. Her biography of the renowned American climber Charlie Houston, Brotherhood of the Rope, won the Kekoo Naoroji Award for mountaineering literature. In 2008, Bernadette McDonald won the Kekoo Naoroji Award for an unprecedented second time with Toma Humar.

About the Book

In August, 2005, Toma Humar was trapped on a narrow ledge at 5900 metres on the formidable Rupal Face of Nanga Parbat. He had been attempting a new route, directly up the middle of the highest mountain face in the world solo. After six days he was out of food, almost out of fuel and frequently buried by avalanches. Three helicopters were poised for a brief break in the weather to pluck him off the mountain. Because of the audacity of the climb, the fame of the climber, the high risk associated with the rescue, and the hourly reports posted on his base-camp website, the world was watching. Would this be the most spectacular rescue in climbing history? Or a tragic and very public death in the mountains?

Years before, as communism was collapsing and the Balkans slid into chaos, Humar was unceremoniously conscripted into a dirty war that he despised, where he observed brutal and inhumane atrocities that disgusted him. Finally he did the unthinkable: he left and finally arrived home in what had become a new country Slovenia.

He returned to climbing, and within very few years, he was among the best in the world. Reinhold Messner, among others, called him the most remarkable mountain climber of his generation. His routes are seldom repeated; most consider them to be suicidal; yet he often climbs them solo. As this book was being written, he achieved the first-ever solo ascent of the east summit of Annapurna.

Toma Humar has cooperated with Bernadette McDonald, the distinguished former director of the Banff Festival and author of several books on mountaineering, to tell his utterly remarkable story.

Also by Bernadette McDonald

Voices from the Summit

Extreme Landscape

Whose Water Is It?

Ill Call You in Kathmandu

Brotherhood of the Rope

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Section one

. Toma Humars parents on their wedding day

. Toma Humar, 1971

. Tomas birthday, 1973

. Climbing Lover Overhang

. Sergeja and Toma on their wedding day, 1991

. Painting church steeples, 1988

. Toma and rauf enjoying hot springs, 1994

. rauf at Camp I on Ganesh V

. rauf on ridge between Camps I & II on Ganesh V

. Toma on the summit of Annapurna, 1995

. Climbing Ama Dablams Northwest Face, 1996

. Vanja Furlan at a bivouac on the Northwest Face of Ama Dablam

. Toma with newborn son, Tomi

. The Humar Family, 2001

. Janez Jegli and Carlos Carsolio

. Toma on the summit of Nuptse, 1997

. Sergeja, 1990

. Toma after summiting El Capitans Reticent Wall, 1998

. Triumphant return after soloing the South Face of Dhaulagiri, 1999

. At the Trento Film Festival, 2000

. Toma in intensive care, 2000

. Training at Jannu Base Camp, 2004

. Toma abseiling on Jannu East

Section two

. Stipe Boi filming below Jannu East

. Anda Perdan praying at Jannu Base Camp

. Toma belaying Ale on Aconcagua

. Toma belaying Ale on Cholatse, 2005

. Ale on the summit of Cholatse

. Ale and Toma bivouacking on Nanga Parbats Rupal Face, 2005

. Maja and Toma

. Toma greeting Steve House at the Rupal Face Base Camp

. Toma kisses the ground after being rescued

. Toma at Base Camp in obvious pain and distress

. Toma embracing his Sirdar, Javed

. Portrait of Toma taken below Lhotses South Face, 2006

. Elizabeth Hawley with Toma

. Rock island on the South Face of Annapurna

. View from Annapurnas East Ridge

All photographs are reproduced courtesy of Toma Humar.

Maps

. Himalayas

. Ama Dablam

. Nuptse

. Bobaye

. Dhaulagiri

. Annapurna

FOREWORD

REINHOLD MESSNER

I have had the great fortune to climb all over the world. I have also met many climbers who have accomplished much more difficult things than I. Toma Humar is one of these climbers.

Modern mountaineering is a British and central European invention. Further developments were made in the USA, in Japan and, above all, in the countries on the other side of the former Iron Curtain. Finally, it was Slovenian climbers who took alpinism one step further. The extent to which Slovenian mountaineers have dominated big-wall mountaineering over the last decade is illustrated by their impressive routes on the South-West Face of Shishapangma (2,150 metres, 1989), the South-East Face of Api (2,600 metres), the North-West Face of Bobaye (2,500 metres), the South Face of Nampa (1,950 metres, all 1996) and the North Face of Gyachung Khang (1999). The new routes that have been climbed in the last decade would have been unthinkable in the 1980s. Only the very best dare to attempt the big problems, and drama, failure and tragedy are, unfortunately, an integral part of the game.

It was the Slovenians Vanja Furlan and Toma Humar who made the first ascent of the 1,650-metre-high, extremely difficult West Face of Ama Dablam from 30 April to 4 May, 1996, in alpine style. They dedicated their route to the passionate big-wall climber, Slovenian Stane Belak, who made the first ascents of the South Face of Makalu and the right-hand side of the South Face of Dhaulagiri, and then lost his life in December 1995 in the Julian Alps.

Then, Toma Humar and Janez Jegli made an alpine-style ascent of the extremely difficult 2,500-metre West Face of the North-West Summit of Nuptse. Jegli had gone on ahead a short way below the top, reached the summit at 1.00 p.m. and waved. A short while later, Humar reached the highest point, but failed to meet up with his partner. He could see his footsteps on the south side of the ridge, caught a very brief glimpse of Jegli and shouted to him. The wind was blowing in gusts as Humar reached the last of his partners tracks. He saw only the radio: Jegli was gone.

Then it was Dhaulagiri. For a long time, Dhaulagiri (8,167 metres), a peak that rises high above the subtropical jungle of Nepal, was considered to be the highest mountain in the world. Now, this elegant summit visible in clear weather from Pokhara takes its rightful place as the sixth highest of the fourteen eight-thousanders. Even its normal route, the North-East Ridge first climbed in 1960 by an international expedition led by the Swiss climber Max Eiselin is difficult. Its south flank, described by Professor G.O. Dyhrenfurth as one of the most terrifying walls in the Himalayas, was the highest unclimbed mountain face in the world.

Incredibly steep, this giant face was the objective of a small expedition that I organised and led in the pre-monsoon season in 1977. I joined forces with Peter Habeler, my tried and trusted partner on Hidden Peak in 1975, and for the extremely difficult and hard enterprise, we invited two additional top climbers of international repute: Michael Covington, one of the top American rock climbers, and Otto Wiedemann, one of the best young German mountaineers.

But the South Face of Dhaulagiri is more than just a Big Wall. It is secretive and it kept its secrets. Like an oracle of an old Gurkha soldier from Bega: Dhaulagiri is like five fingers on a hand. The first and last fingers are deadly; the two others too are dangerous. Only the forefinger points the way to the summit.

Next page