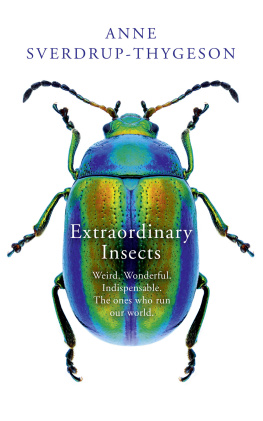

First published by J.M. Stenersens Forlag AS 2018

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA, Norwegian Literature Abroad

Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Nature is nowhere as great as in its smallest creatures

PLINY THE ELDER

Naturalis historia 11, 1.4,

Ca. 79 CE

I ve always liked spending time outdoors, especially in the forest. Preferably in places where signs of human life are few and far between, and evidence of our modern impact scarce; among trees older than any living person, trees that have toppled headlong, nose-diving into the springy moss. Here they lie, in prostrate silence, as life continues its eternal round dance.

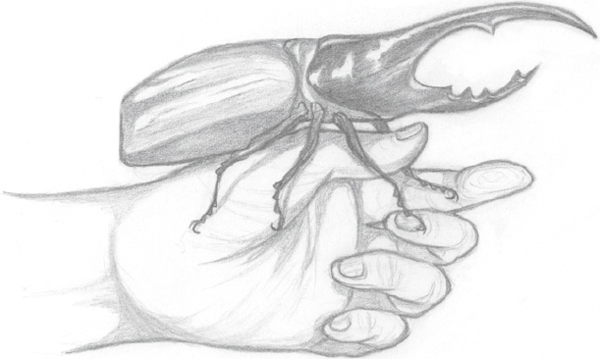

The insects come to the dead trees in their hordes. Bark beetles party in the sap that ferments beneath the bark, longhorn beetle larvae trace ingenious patterns on the surface of the wood, and like tiny crocodiles, wireworms greedily snap up anything that moves within the rotting wood. Together, thousands of insects, fungi and bacteria work to break down dead matter and transform it into new life.

I feel incredibly lucky to be able to research such an exciting topic, because I have a fantastic job: I am a professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), where I work as a scientist, teacher and communicator. One day I might be reading about new research, digging deep and losing myself in scientific detail. The next, Im due to give a lecture and have to look for an overarching structure in a given subject area, find examples and illustrate why the issue matters to you and me. Maybe it will end up as a post on our research blog, Insektkologene (The Insect Ecologists).

Sometimes I work outdoors. I seek out ancient, hollow oaks or map forests affected to varying degrees by logging. All this I do in the company of my wonderful colleagues and students.

When I tell people I work with insects, they often ask me: What good are wasps? Or: Why do we even need mosquitoes and deer flies? Because some insects are a nuisance, of course. The truth is, though, that they are a vanishingly small minority compared with the teeming myriads of tiny critters that all do their little bit to save your life, every single day. But lets start with the more troublesome ones. I have three answers.

First of all, these annoying insects are useful to nature. Mosquitoes and gnats are vital food for fish, birds, bats and other creatures. In the highlands and the far north of Norway, in particular, swarms of flies and mosquitoes are crucial to animals much larger than themselves, and on a vast scale. During the short, hectic Arctic summer, insect swarms can determine where the large reindeer flocks graze, trample the earth and deposit nutrition in the form of dung. This has ripple effects that influence the whole ecosystem. Similarly, wasps are useful, both for us and other creatures. They help pollinate plants, gobble up pests whose numbers wed rather keep down and provide food for honey buzzards and countless other species.

Secondly, helpful solutions may await us where we least expect them. This even applies to creatures we see as disgusting nuisances. For example, blow flies can cleanse hard-to-heal wounds, while mealworms turn out to be able to digest plastic, and scientists are currently investigating the use of cockroaches for rescue work in collapsed or severely polluted buildings, as we will see in .

Thirdly, many people think that all species should have the opportunity to achieve their full life potential that we humans have no right to play fast and loose with species diversity driven by short-sighted judgements about which species we see as cute or useful. This means we have a moral duty to take the best possible care of our planets myriad creatures including critters that do not engage in any visible value creation, insects that do not have soft fur and big brown eyes and species we see no point in.

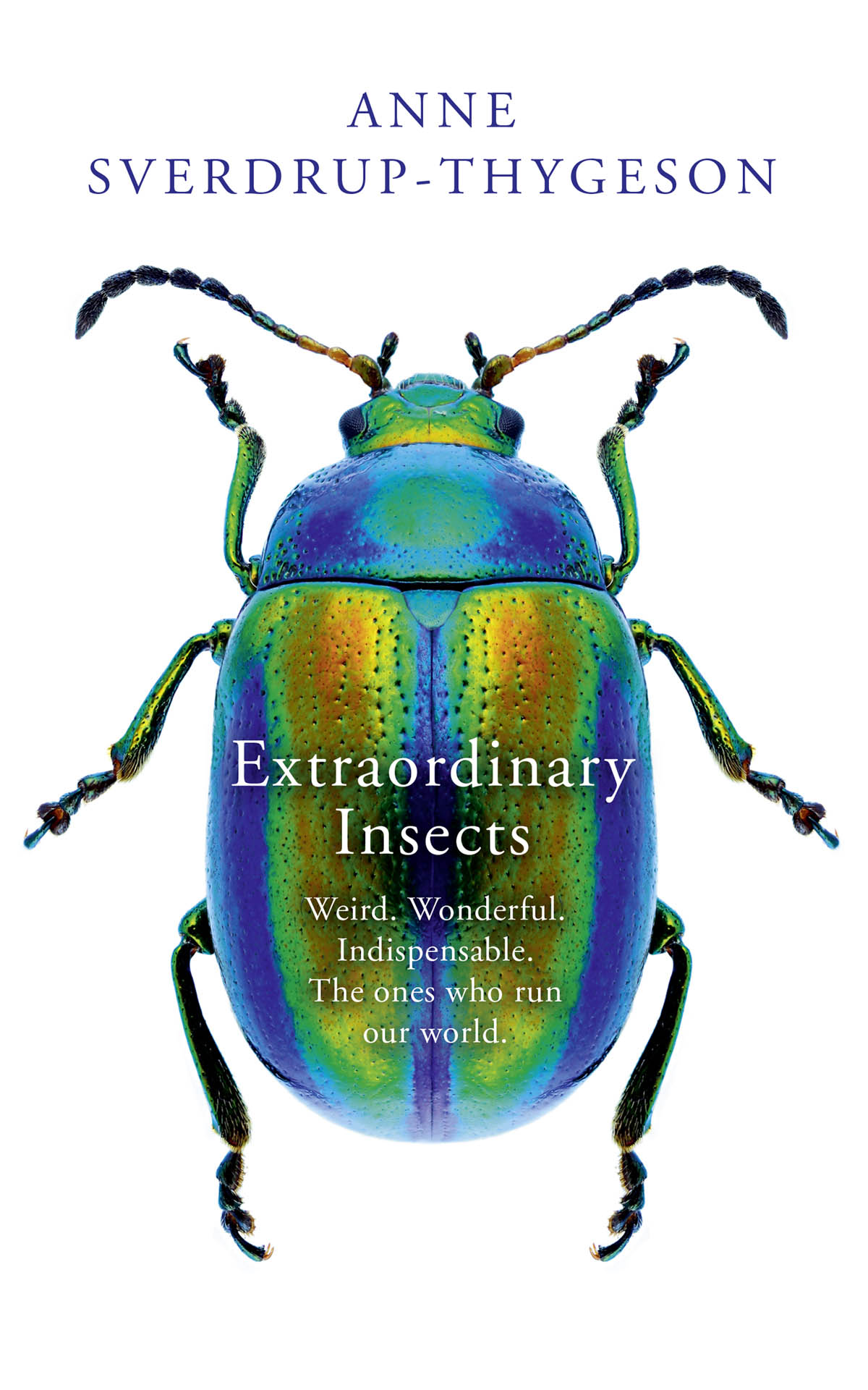

Nature is bewildering in its complexity and insects are a significant part of these ingeniously constructed systems in which we humans are just one species among millions of others. That is why this book will deal with the very smallest among us: all the strange, beautiful and bizarre insects underpinning the world as we know it.

The first part of the book is about the insects themselves. In ): the daily struggle to eat or be eaten in which every creature battles to pass on its own genes. Yet there is still room for collaboration, in countless peculiar ways.

The rest of the book is about insects intimate relationship with one particular species: us humans. How they contribute to our food supply (, I consider how these tiny helpers of ours are getting along, and how you and I can help improve their lot. Because we humans rely on insects getting their job done. We need them for pollination, decomposition and soil formation; to serve as food for other animals, keep harmful organisms in check, disperse seeds, help us in our research and inspire us with their smart solutions. Insects are natures little cogs that make the world go round.

T here are more than 200 million insects for every human being living on Planet Earth today. As you sit reading this sentence, between one and 10 quintillion insects are shuffling and crawling and flapping around on the planet, outnumbering the grains of sand on all the worlds beaches. Like it or not, they have you surrounded, because Earth is the planet of the insects.

There are so very many of them that its difficult to take it in, and they are everywhere: in forests and lakes, meadows and rivers, tundra and mountains. Stoneflies live in the chilly heights of the Himalayas at altitudes of 6,000 metres, while mosquito larvae inhabit the piping-hot springs of Yellowstone, where temperatures exceed 50C. In the eternal darkness of the worlds deepest caverns live blind cave midges. Insects also live in baptismal fonts, computers, oil puddles, and in the acid and bile of a horses stomach. They live in deserts, beneath the ice on frozen seas, in the snow and in the nostrils of walruses.