This book could not have been written without the generosity of the neuroscientists, psychologists, and psychiatrists who cleared spaces in their busy schedules for interviews to describe for me their adventures in the uncharted territory where the brain, the mind, and well-being come together. Id like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Jon Kabat-Zinn and Judson Brewer at the University of Massachusetts Medical School; Richard Davidson at the University of WisconsinMadison; Herbert Benson at Massachusetts General Hospital; Zindel Segal at the University of Toronto; Willem Kuyken and Daniel Freeman at the University of Oxford; Britta Hlzel at the Technische Universitt Mnchen; Simon Wessely at the Royal College of Psychiatrists; David Haslam at NICE; Sarah Bowen at the University of Washington; and Judith Soulsby at the University of Bangor.

I also owe a huge debt of gratitude to the monks, nuns, and lay staff of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery for the warmth of their hospitality, and in particular to the abbot Ajahn Amaro, whose wise words remain an inspiration. Amaravati embodies an ancient Eastern philosophy that runs counter to almost everything Westerners are brought up to believe about the pursuit of happiness. That this place and its philosophy are thriving in the twenty-first century was a source of wonder to me.

Siddhrthas Brain is a product of that wonder. Id like to thank my agent, Peter Tallack, for believing in this strange hybrid of spirituality, neuroscience, and psychiatry when it was no more than a sketchy idea, and for his and Tisse Takagis sterling work transforming it into a viable proposal. It caught the eye of the editor Peter Hubbard at William Morrow/HarperCollins, who was brave or crazy enough to take a gamble on this first-time author. I have him and his excellent team of copy editors and designers to thank for the book you have in your hands or on your screen. I am grateful also to Louisa Pritchard for her tireless work selling the rights to translations around the world.

Finally, I have my lovely family and friends to thank for their unfailing support, especially in the early stages of the project when they probably assumed some kind of midlife crisis was under way. In particular I would like to thank Charlotte for rescuing me when, for a few days, it really did look as though things were starting to unravel. And I will be forever indebted to Art, who did more than anyone else to set my feet on this path.

JAMES KINGSLAND is a science and medical journalist with twenty-five years of experience working for publications such as New Scientist, Nature, and most recently the Guardian (UK), where he was a commissioning editor and a contributor for its Notes & Theories blog. On his own blog, Plastic Brain, he writes about neuroscience and Buddhist psychology.

www.plasticbrainblog.com

@JamesAKingsland

@JamesAKingsland

Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at hc.com

Our life is shaped by our mind; we become what we think. Suffering follows an evil thought as the wheels of a cart follow the oxen that draw it.

The Dhammapada (translated by

Eknath Easwaran), verse 1

Picture a lush grove on a still, warm evening in late spring. The throb of cicadas and the chatter of a river as it carves a path through the forested landscape are the only sounds. At the center of the grove stands an old fig tree with a broad trunk and fresh green, heart-shaped leaves with long, tapering tips. And, sitting cross-legged beneath the tree, almost hidden in the shadow cast by the setting sun, you might just make out the slight figure of a man wrapped in filthy rags. Look closer and you cant help but notice his sunken eyes, the dark caverns of his cheeks, and how loosely the rags hang from his bony shoulders, though he sits bolt uprightas solid and unwavering as the ancient tree.

Our story begins by the sandy banks of the Nerajar River near the village of Uruvel, in northern India. The birth of Christ lies more than four hundred years in the future, and the foundations of science and philosophy are still being laid by the great thinkers of ancient Greece. The emaciated Indian sitting unmoving in the darkness beneath the tree is Siddhrtha Gautama, a homeless man in his midthirties. Just a few minutes before we arrived he was finishing a meal of rice cooked in coconut milk, scraping the last grains from the bowl. It was his first square meal in a very long time and may well have saved him from a premature, inglorious death by starvation. Describing his predicament in later life, he would say that after years of brutal self-denial his hair had started to fall out. His limbs looked like the jointed segments of vine stems or bamboo stems. Because of eating so little my backside became like a camels hoof. His ribs jutted from his chest like the crazy rafters of an old, roofless barn, his eyes had sunk so deep into their sockets they were like the gleam of water deep in a well.

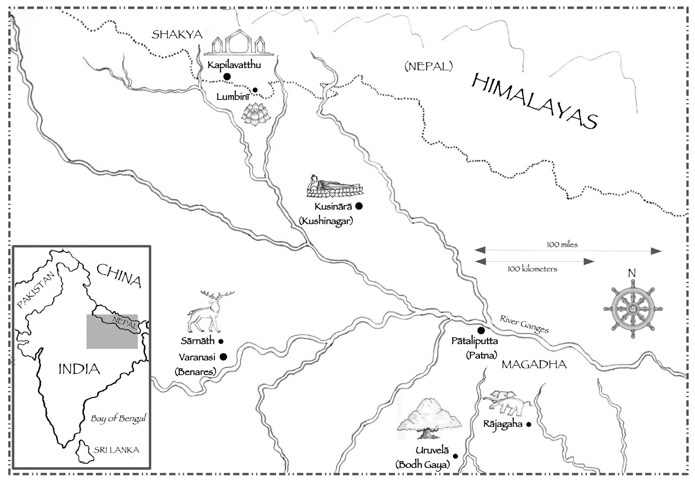

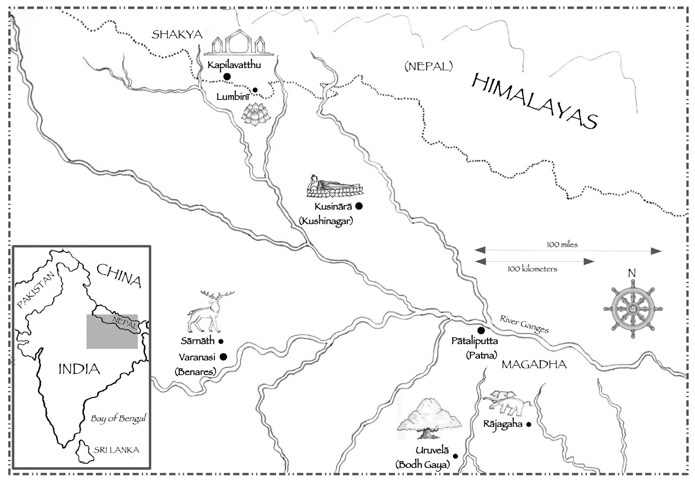

His father, Suddhodanaa wealthy and influential man who was the elected chief or king of the Shakya clan in their remote northern republic in the foothills of the Himalayaswould have been horrified to see him in this state. Six years previously, Prince Siddhrtha was living in great comfort in the grand family home at Kapilavatthu (Kapilavastu), the republics capital, about 230 miles northwest of Uruvel, near the border between what is now southern Nepal and the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. His family were members of the governing warrior class, the kshatriya . According to legend, when Siddhrtha was a baby, eight brahmin priests foretold that he would become either an all-conquering ruler or he would renounce the world to fulfill a spiritual destiny. King Suddhodana wasnt taking any chances with his sons future career. He spared no effort or expense to ensure that as Siddhrtha grew up, he enjoyed every luxury and experienced no discomfort. Lotus pools were made for me at my fathers house solely for my use; in one, blue lotuses flowered, in another white, and in another red. I used no sandalwood that was not from Benares. My turban, tunic, lower garments and cloak were all of Benares cloth. A white sunshade was held over me day and night so that I would not be troubled by cold or heat, dust or grit or dew. His father ordered the palace guards to prevent him from encountering any hint of sickness, aging, or death. The king believed that if he could only shield his son from all lifes unpleasantness, he would not be drawn to the spiritual life and would instead take the worldly path and become a powerful leader.

Key locations in the Buddhas life. Map by Narasit Nuad-o-Lo.

Siddhrtha reached the age of twenty-nine, and everything seemed to be going according to plan. He had grown up handsome and strong, winning the hand of a beautiful young woman in the traditional mannerin an archery contest. His wife had recently given birth to a healthy baby son. But, despite his fathers best efforts, eventually and inevitably Siddhrtha came face-to-face with the realities of life. While he was out driving one morning with his charioteer in the pleasure park, they encountered a senile old man. Siddhrtha asked the charioteer what was wrong with the man. This was what happened to people the longer they lived, he explainedtheir minds and bodies steadily declined. Shortly afterward they came across a sick man and later a corpse. In the end there was no escaping these things. The richest, most powerful man in the world could not hold back sickness, aging, and death. It dawned on Siddhrtha that sooner or later even the most beautiful and wonderful things in his lifethe most sensual pleasureswould fade. Nothing would be perfect, nothing permanent. Everything he had come to love was subject to change, death, and decay.

@JamesAKingsland

@JamesAKingsland