ALSO BY PTOLEMY TOMPKINS

This Tree Grows Out of Hell: Mesoamerica and

the Search for the Magical Body

The Monkey in Art

Paradise Fever: Growing Up in the Shadow of the New Age

The Beaten Path: Field Notes on Getting

Wise in a Wisdom-Crazy World

For Francie

CONTENTS

5

AUTHORS NOTE

Many people disapprove of calling a people, practice, or belief primitive these days, on the grounds that the word smacks of antiquated beliefs about the superiority of modern Western culture and the inferiority of peoples less technologically advanced (another tricky word). I, however, have always liked the sound and feel of primitive, and dislike the idea that just because it was used poorly for a while it now cant be used at all. In what follows, it should be kept in mind that, of its several dictionary meanings, I generally intend its first (of or relating to an earliest or original stage or state; primeval) rather than its second (characterized by simplicity or crudity; unsophisticated).

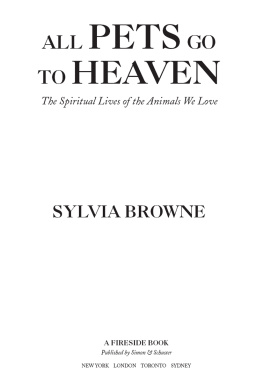

This book started out with the working title The Divine Life of Pets, but shifted to its current one after I noticed two things: first, its really not pets Im talking about, but all animals; second, even if I were just talking about pets, the word would still be best left out of the title, as pet is becoming, in our politically conscious world, ever more of a loaded term. Animal companion is fast becoming the favored term for a domesticated animal kept for pleasure rather than utility, and while I see the logic of this switch, the term doesnt always flow easily off the tongueor onto my computer screen for that matter. Consequently, while removing it from the title, Ive chosen to keep the word pets in my text. All the same, the impetus behind the move away from the word pet is, as I try to show in the story I tell here, a laudable one. It acknowledges what every pet owner knows: that the animals we keep are not possessions but fellow travelers on our lifes journey, and it is precisely by being both (a) animals and (b) companions that they perform a dual service: not only are they our friends, but they are links back to a time when the shape and character of that journey was very different than it is now. As the novelist Milan Kundera wrote, in a passage that (if we substitute animals at large for dogs) could serve as a fitting epigraph for this entire book: Dogs are our link to paradise. They dont know evil or jealousy or discontent. To sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boringit was peace.

INTRODUCTION

The eyes of an animal have the capacity of a great language.

Martin Buber (18781965)

T he world is well supplied with interesting books about animals. Some focus on animal behavior. Some discuss the complexand often controversialsubject of animals and ethics: how we should behave toward our fellow creatures, what rights they do or dont have, and what responsibilities we humans have toward them as a result. Others discuss the fascinating subject of communication between humans and animals: whether certain nonhuman creatures possess at least the rudiments of language, and what possibilities there might be for genuine communication between them and us if they do.

This book isnt about any of those things. I can think of no better way to explain what it is about than to tell the story of a small white dog that I met on the Yucatn Peninsula in the fall of 1974.

I was twelve at the time, tagging along with my father while he, my stepmother, and two other friends toured the region as part of the research my father was doing for a book on its ancient pyramid cultures. Pyramids and temples interested me not in the least at that age, and while the adults around me focused their attentions on one ancient pile of rocks after another, I looked for animals.

Most children like animals to some degree, but theres a certain kind of young person who does more than just like them: he identifies with them. For this latter kind of child, animals are more consequential, more congenialand in certain ways at least, more real than humans are. If childhood is a period in which we are coaxed, willingly or otherwise, out of a state of natural innocence and into a state of acculturation to the human condition, animal-oriented children have a larger-than-average suspicion of this transition. For them the trade of animal innocence for human knowledge is one thats quite simply not worth making.

That was the kind of kid I was. So while the cultural aspects of my fathers Yucatn adventure left me decidedly indifferent on that trip, the sea and jungle and the creatures that filled them gave me plenty of reason to be glad Id been brought along all the same.

Not that all the animals I encountered were all that alien or exotic. In fact, the first ones I usually saw in each new town or city we visited were dogs. They were everywhere: hovering at the fringes of the outdoor restaurants where we ate, lounging in the courtyards of the hotelshungry, obsequious, and always ready to bolt at the first sudden motion from a human.

Though few people seemed to be interested in doing so, these dogs were easy to win over if you cared to try. Approaching them slowly and holding out my hand, Id find that all but the most skittish would soon start wagging their tails and crowding around, overjoyedor so it seemed to methat someone was at last paying them a little attention. It didnt hurt if you had some food to offer as well, and in more than one of the endless string of hotels we stayed in, my father, looking around for some bag of restaurant leftovers hed set aside, would learn with irritation that I had parceled it out to whatever particular set of dogs were camped outside.

On the day in question we got up early and took a two-hour jeep ride to a set of ruins deep in the jungle. Near the ruins were a small group of huts, one of which had a generator-powered cooler full of soda and beer, and a grubby but serviceable snack counter. Lounging in front of the counter was the usual handful of dogs. My eye immediately fell on one of thema singularly small, singularly pathetic-looking white female that didnt look like she was more than a few months old. Thumping her bony tail in the dust as I approached, she responded to my outstretched hand with tentative, sheepish, but scarcely concealed excitement. At last, her look seemed to say, someones noticed Im here.

This dog, who I christened Penny in honor of a single small copper-colored spot on her shoulder, followed along as we toured the temples, her tail swinging with such enthusiasm that it kept threatening to topple her over. Penny was so painfully thin that I decided Id give her an extra-large portion of my lunch when we were back at the storefront.

Once we got there, however, my stepmother read my mind.

Ptolly, she said as one of our guides handed me a plate of tortillas, chicken, and beans, dont feed that dog.

Why not?

Because its not respectful to the people who live here. They have little enough as it is, and its rude to throw food away right in front of them.

Giving food to a dog isnt throwing it away, I said acidly.

It is when youre in a country like this, my stepmother said. You cant get emotionally attached to every animal you see down here. It isnt realistic.