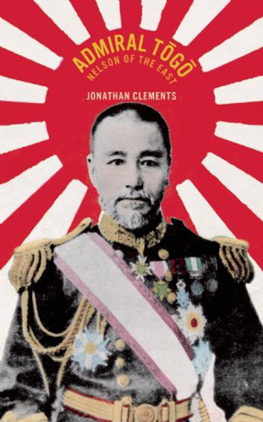

Jonathan Clements is the author of many books about East Asian history, including A Brief History of the Samurai, Modern Japan: All That Matters, and biographies of Admiral Tg and Prince Saionji Kinmochi. His Anime: A History was a 2014 CHOICE selection as one of the years outstanding academic titles. He wrote the Asia and the World chapters of the Oxford University Press Big Ideas history series for schools, which won an Australian Publishing Association award for Excellence in Educational Publishing in 2012.

ALSO BY JONATHAN CLEMENTS

Modern Japan: All That Matters

Anime: A History

The Art of War: A New Translation

A Brief History of Khubilai Khan

A Brief History of the Samurai

Admiral Tg: Nelson of the East

Mannerheim: President, Soldier, Spy

Prince Saionji

Wellington Koo

Wu: The Chinese Empress Who Schemed, Seduced and Murdered Her Way to Become a Living God

Marco Polo

The First Emperor of China

Confucius: A Biography

Pirate King: Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty

The Moon in the Pines (published in paperback as Zen Haiku)

Christs Samurai

The true story of the Shimabara Rebellion

JONATHAN CLEMENTS

ROBINSON

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Robinson

Copyright Jonathan Clements, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-47213-671-8

Robinson

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

www.littlebrown.co.uk

In Memory of

Father Andrew Dorricott

and

Father James Hannon

Contents

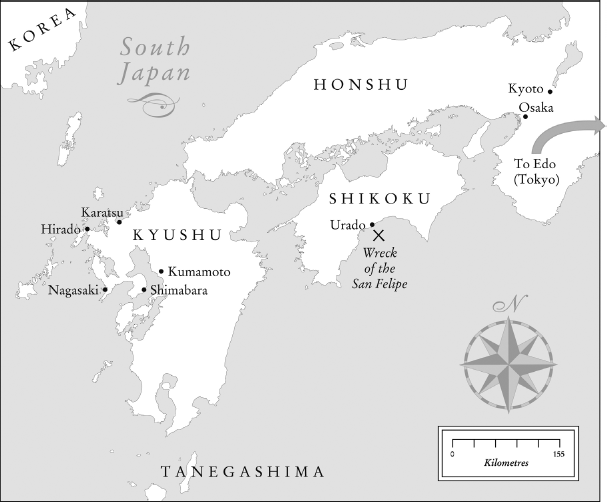

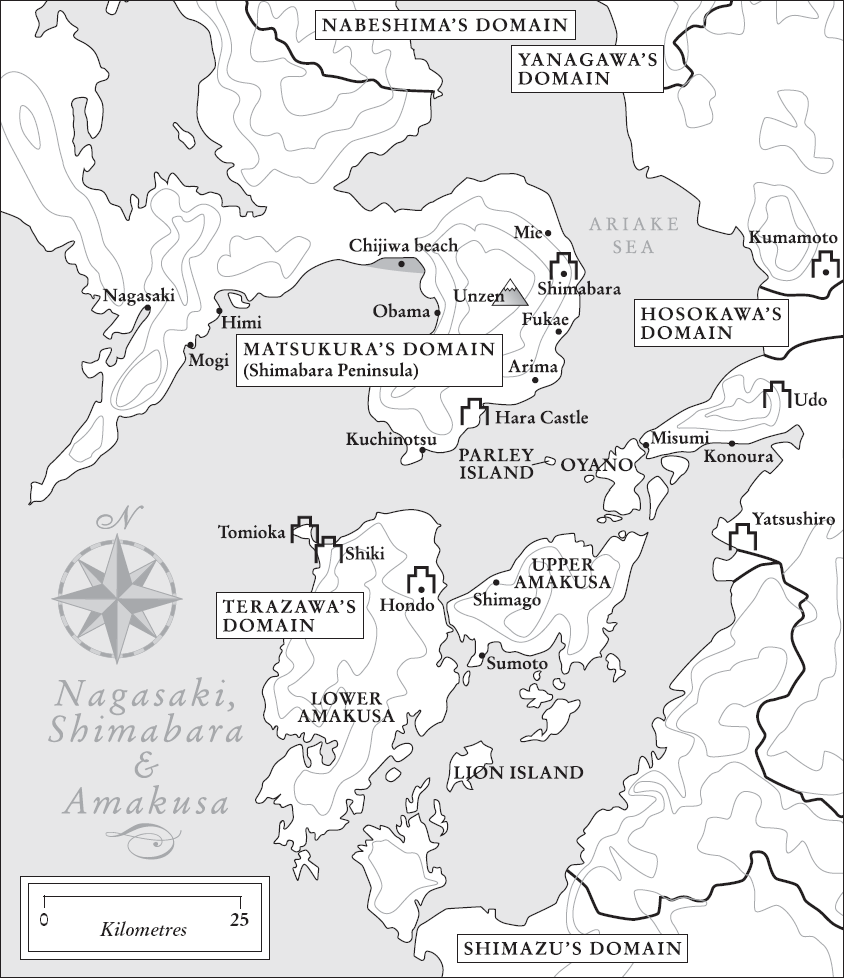

Maps

At times when wading through the immense amount of material relating to the Shimabara Rebellion, I felt, like Jerome Amakusa, that I was foolishly attempting to measure out the sea with a shell. Kameshi Kenji, curator of the Christian Museum collection at its temporary home in the Hondo Municipal Museum of History and Folklore, was generous with his time, advice and help. He confirmed my suspicions about the past of the rebel ringleaders, allowed me to take several crucial photographs, and sent me packing with an armload of photocopies and local history documents.

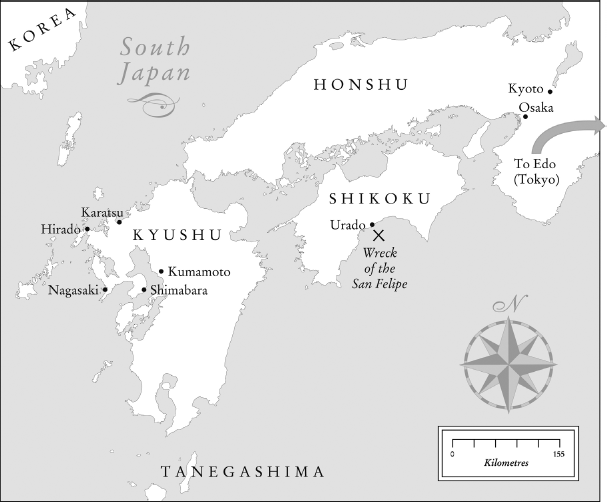

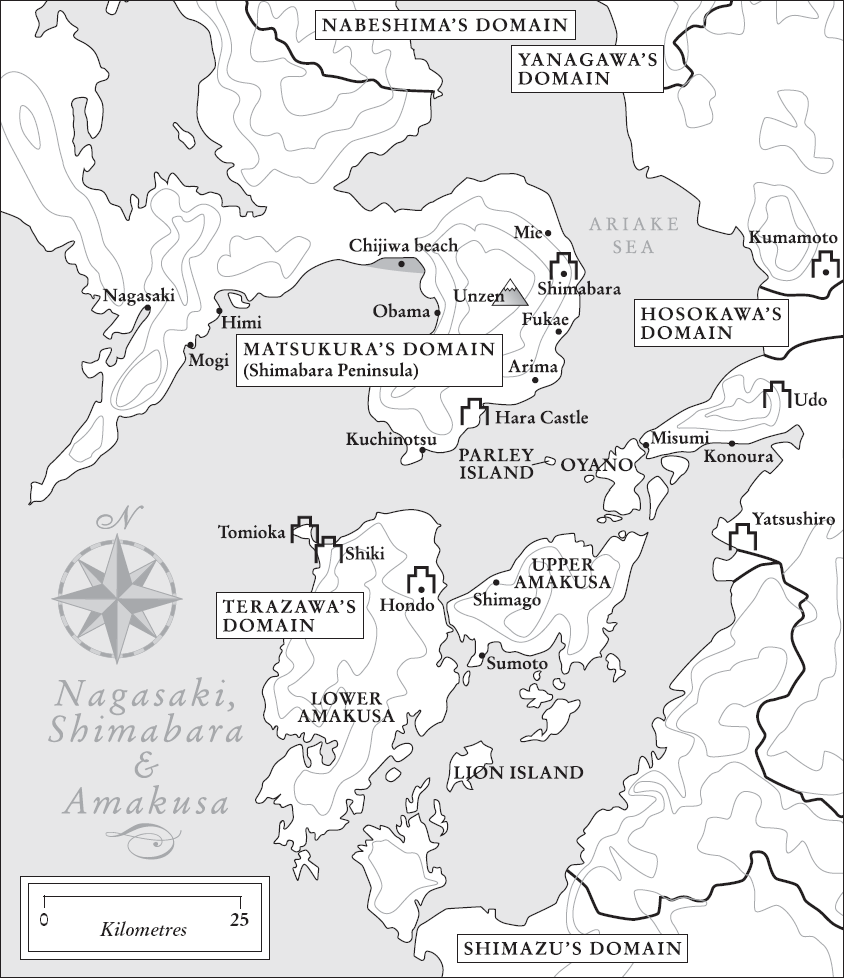

My photographer (and wife) Kati Clements carried a hefty sack of camera equipment from Nagoya to Nagasaki and all points in between, learning as she went about the story, so that by the time we reached Amakusa it was she who found the site of the Battle of Hondo. My research assistant Tamamuro Motoko helped with sourcing of materials from her own family archives, and never quite expected her working life to be caught up with arguments over the names of flowers, Buddhist religious terminology, or the Japanese pronunciation of Latin terms. Martin Stiff drew and re-drew maps of places that no longer existed, and learned more about early Tokugawa era clan liveries than he ever really wanted to.

Sat Hiroyuki of Londons Jaltour arranged an itinerary that took me right across both the Shimabara peninsula and the Amakusa archipelago, including Hara, Unzen, yano and Tomioka. He had made the same pilgrimage himself in his youth, and his diligence ensured that I would not need to walk on water at any point. I should point out, however, that the reader will no longer be able to duplicate my journey precisely the railway line south of Shimabara to Hara Castle has since been shut down and replaced by a bus.

My agent Chelsey Fox of Fox & Howard has overseen this project with all the cunning of a Hosokawa, and the tireless patience of a Matsudaira. I would also like to thank the staff of the Library of Londons School of Oriental and African Studies, as well the Nagasaki Memorial Museum of the Twenty-Six Martyrs, the Nagoya Museum of Christian Relics, the Amakusa Shir Memorial Hall in yano, the Tomioka Castle Visitors Centre, the Hondo branch of the Amakusa Tourist Board, and Nagasaki Dejima, all of which have contributed in some way with information, exhibits, hints and legends. I am grateful to Dominic Clements, Andrew Deacon, Sharon Gosling, Alex McLaren, Reiko McLaren, Adam Newell, Ellis Tinios and Stephen Turnbull for many small kindnesses from the loaning of books to the giving of lifts. In 1993, my father, Michael Clements, developed the perplexing conviction that I would one day need a 300-year-old copy of Crassets The History of the Church of Japan, despite no evidence to support this. It might come in handy, he said, and he was right, eventually. There are also many others who remain nameless, chiefly Japanese locals in Kysh, who made researching and writing this book a joy of discovery, from the kindly bus driver who decided on his own initiative to take me to the site of Jeromes camp in Hondo, to the Shimabara waitress who decided I needed a bowl of guzni.

In 1638, the ruler of Japan ordered a crusade against his own subjects, a holocaust upon the men, women and children of a doomsday cult in the remote south-western district of Shimabara. Introduced a century earlier by foreign missionaries, the sect was said to harbour dark designs to overthrow the government. Its teachers read and wrote a dead language, impenetrable to all but the innermost circle of believers. Its leaders preached love and kindness, but had helped local warlords acquire firearms. They encouraged believers to cast aside their earthly allegiances and swear loyalty to a foreign god-emperor. They urged their followers to seek paradise in terrible martyrdoms and, for many years, the Japanese governments tor turers and executioners had obliged them.

The hated cult was in open revolt, led, it was said, by a boy sorcerer. Farmers claiming to have the blessing of an alien god had bested trained samurai in combat and proclaimed that fires in the sky would soon bring about the end of the world. The Shgun called old soldiers out of retirement for one last battle before peace could be declared in Japan. For there to be an end to war, he said, the Christians would have to die.

For centuries, the Shimabara Rebellion was a taboo subject in Japan, its leader a bogeyman not to be spoken of, its battles and heroes conspicuously absent from plays and prints. Its supposed instigator was one Jerome Amakusa, a.k.a. Masuda Shir, Tokisada, Francisco, Nirada. He has a legion of names, and little else that is verifiable. He may have been a charismatic youth, welcomed by the underground Christians of a poverty-stricken region as their long-awaited saviour. Or he may have been the unwitting pawn of a handful of aging war veterans, who sought to add an apocalyptic sheen to a mundane peasant uprising. In the years that followed, Jerome was a shadowy figure, a symbol of revolution itself in an age when dissent was forbidden.

Next page