CONTENTS

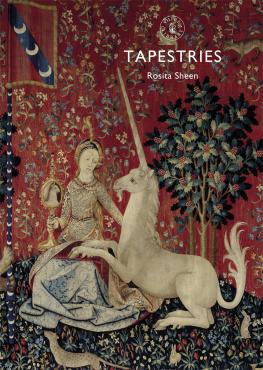

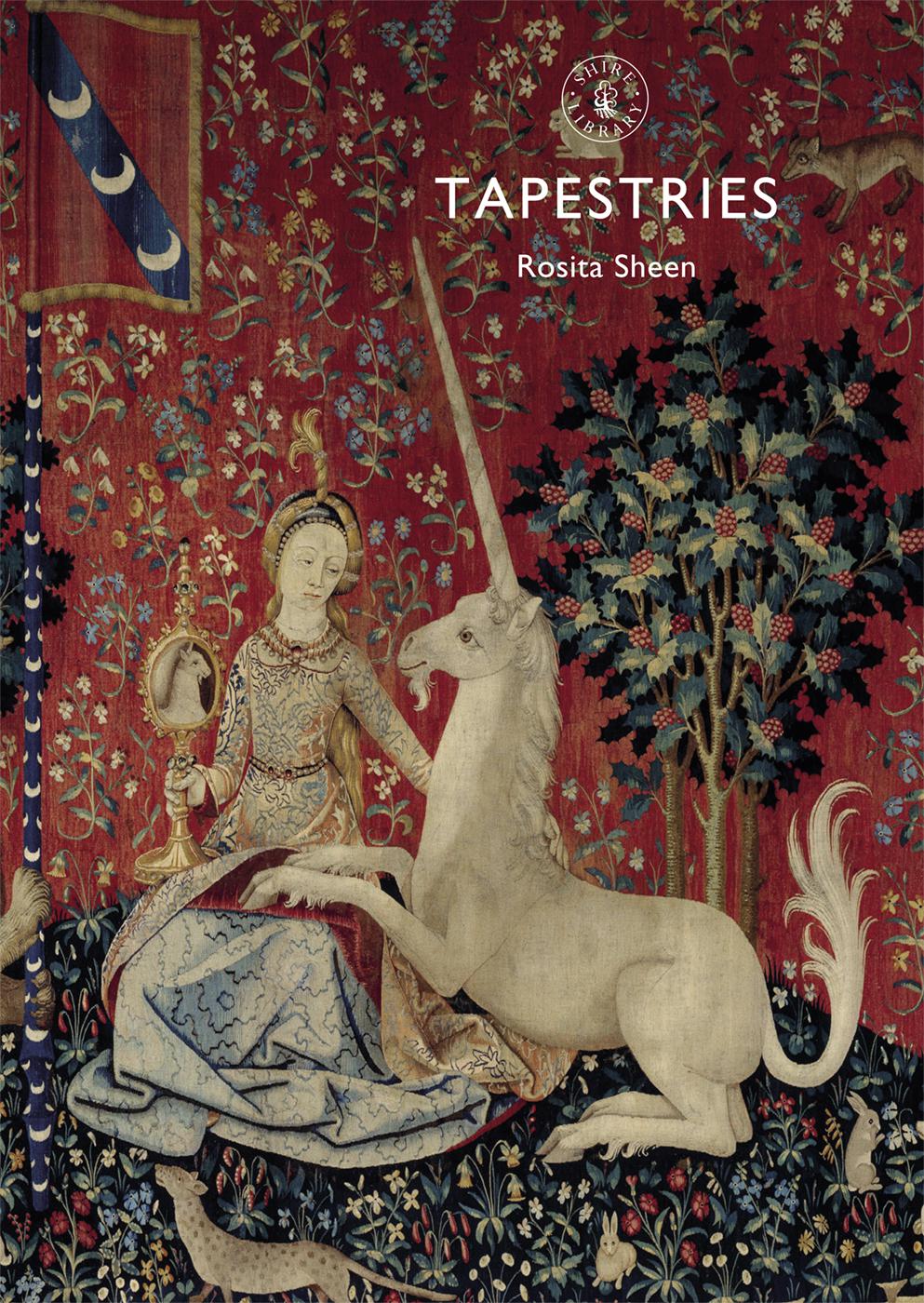

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

WHAT IS A TAPESTRY?

R ATHER LIKE H OOVER (vacuum cleaner) and Biro (ballpoint pen), the word tapestry is used today as a catch-all term for numerous types of fabric. True tapestry, of the sort you would find in almost any large, old country house, is a woven fabric distinguished from cloth we might wear by the use of discontinuous weft threads, where one pick (row) of weft may have many different coloured threads. The change in colour of the threads across the tapestry creates a design, which often tells a story. Tapestry can today be machine woven but in the past it was woven by hand; even now, true tapestry is hand woven. Embroidery, cross-stitch, canvas work and so-called tapestry kits are not actually tapestries. The most famous tapestry of all, the Bayeux Tapestry , is in fact an embroidery, worked in woollen threads on a linen background. Today the word is most often associated with wall hangings but may also include furnishings and even garments such as copes (cloaks worn by the clergy). We cannot be sure that the different words used in the past and translated as tapestry have the same meaning today.

In order fully to appreciate tapestries it is important to understand how they are made. Although the finished piece may be extremely complex, tapestries are woven on a simple type of loom, that is, a frame that holds the threads known as warps. This might be as small as a picture frame a few inches long or as huge as will fit into the space available. The weft threads go over and under the warps to make the design, but only in the areas where that particular co lour is needed.

Traditionally tapestries might be produced on either an upright loom called a high warp ( haute lisse ) or a horizontal loom called a low warp ( basse lisse ). The most usual was the high warp, though the end product is little different whichever is used. On the haute lisse one end of each warp thread is attached to a roller beam at the top and the other end at the bottom for the length of tapestry you want to produce and begins wound around the top beam. Traditionally the weaver sits at the back of warps and they are wound down to the bottom roller as the weaving progresses. With the basse lisse the weaver sits up to the loom and again the warps are wound from a roller at the back towards the weaver as sections are completed. For a large piece made on either loom two, three, four or more weavers may sit side by side, each working on a different section of the design.

The Bayeux Tapestry , which is really an embroidery, showing the comet that appeared in the sky in 1066 and was seen as a bad omen.

Weavers working on two haute-lisse or high-warp looms. Note the fixed warp threads, seen here in white.

Tapestry weavers at Aubusson, France, in the late 1940s working on a basse-lisse or low-warp loom.

On a high-warp loom a system of cords is attached to alternate warps and pulled when needed to create a space called a shed so that the weft can be inserted. The same function is done by treadles worked by the feet under a low-warp loom, which has the advantage of leaving both hands free. Weaving is done using bobbins wound with the different colours of yarn. On a large tapestry there will be many bobbins across the work, and they are so shaped as to hold the weft and for the weaver to be able to use the pointed end to beat it down. This gives one of the major characteristics of tapestry, that is, that the warp threads are completely covered by the weft. On a normal cloth weave, known as plain weave or tabby, both warp and weft are e qually visible.

These weavers are working on a piece designed by Eva Rothschild. Note the warp threads (here in black) and the bobbins hanging from the work, which contain the coloured weft.

Master Weaver Philip Sanderson working on his piece Nowhere. Here warp, weft and bobbins are clearly seen. Modern weavers usually work from the front of the piece.

Throughout the weaving process the warps are under constant tension and so have to be of a strong thread. In the past this was most often a high twist wool or linen, though sometimes silk or cotton might be used, and it would be of a neutral colour because it was not going to be seen. Weft is the visible part of the work and again it was most commonly made of wool though other fibres were used. The most elaborate and expensive tapestries had wefts of silk with silver and gold threads in places to sparkle and reflect light.

Unlike painting, which is usually the creation of one person (who until recently would have even made their own paints), tapestry is the culmination of the efforts of a whole range of skilled craftspeople including spinners, dyers, weave rs and artists.

Before you can weave you have to spin. All of this yarn had to be produced by being spun after it had been removed by shearing, that is, cutting the wool off the sheep. There was a time when virtually everyone could spin because they had to. Until the invention of water-powered machines in the eighteenth century, every piece of fabric produced, from silk to sacking and including tapestry, had to b e spun by hand.

For centuries spindles were used for spinning. A spindle in its simplest form is just a stick with a weight at one end, called a whorl, and a notch or hook at either end. The fibres are drawn out by the fingers and the spindle inserts twist to give it strength. When a section of thread has been produced it is unhooked from the notch or hook and wound onto the spindle. This gadget is very cheap to make and very portable. Spinners could be minding the sheep or walking to market or talking to neighbours and have a spindle in their hands. As a result, the spindle has never died out completely and today they are widely available in a huge range of traditional and modern materials. As with looms, spindles in one form or another are found all over the world, producing yarn from whatever plant or animal fibres are to hand locally. Spindle whorls are amongst the commonest finds in archaeological digs because they are usually made of stone or clay (the stick itself will have rotted away), and provide a reliable sign of hu man occupation.