About the Author

Mark Williams is Associate Professor of Global Medieval Literature at the University of Oxford, specializing in Celtic languages and the medieval literature of Ireland and Wales. He is the author of Fiery Shapes: Celestial Portents and Astrology in Ireland and Wales, 7001700 and Irelands Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Celtic Myths

Miranda Aldhouse-Green

The Historical Atlas of the Celtic World

John Haywood

Blood of the Celts

Jean Manco

Be the first to know about our new releases,

exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

Contents

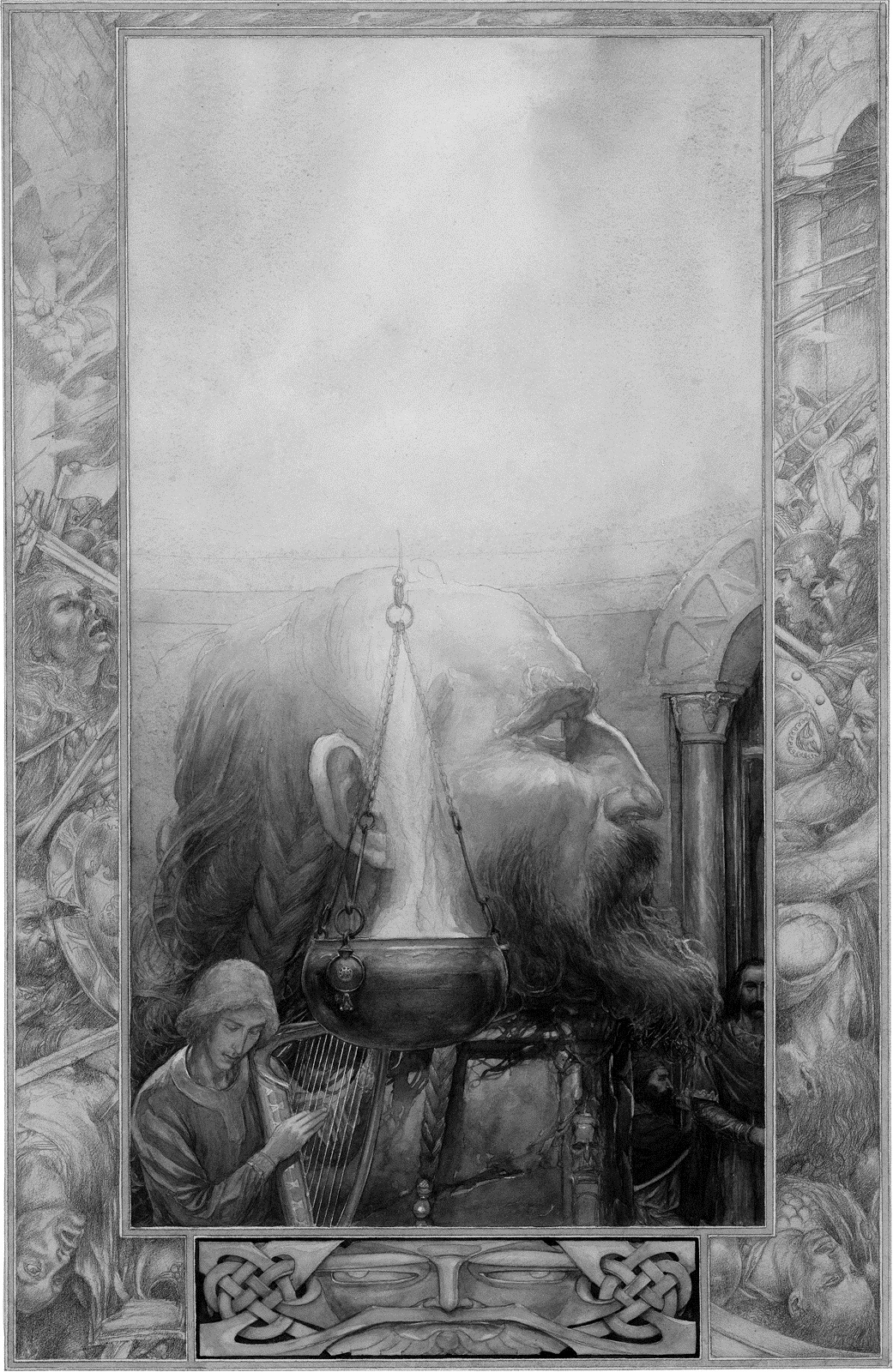

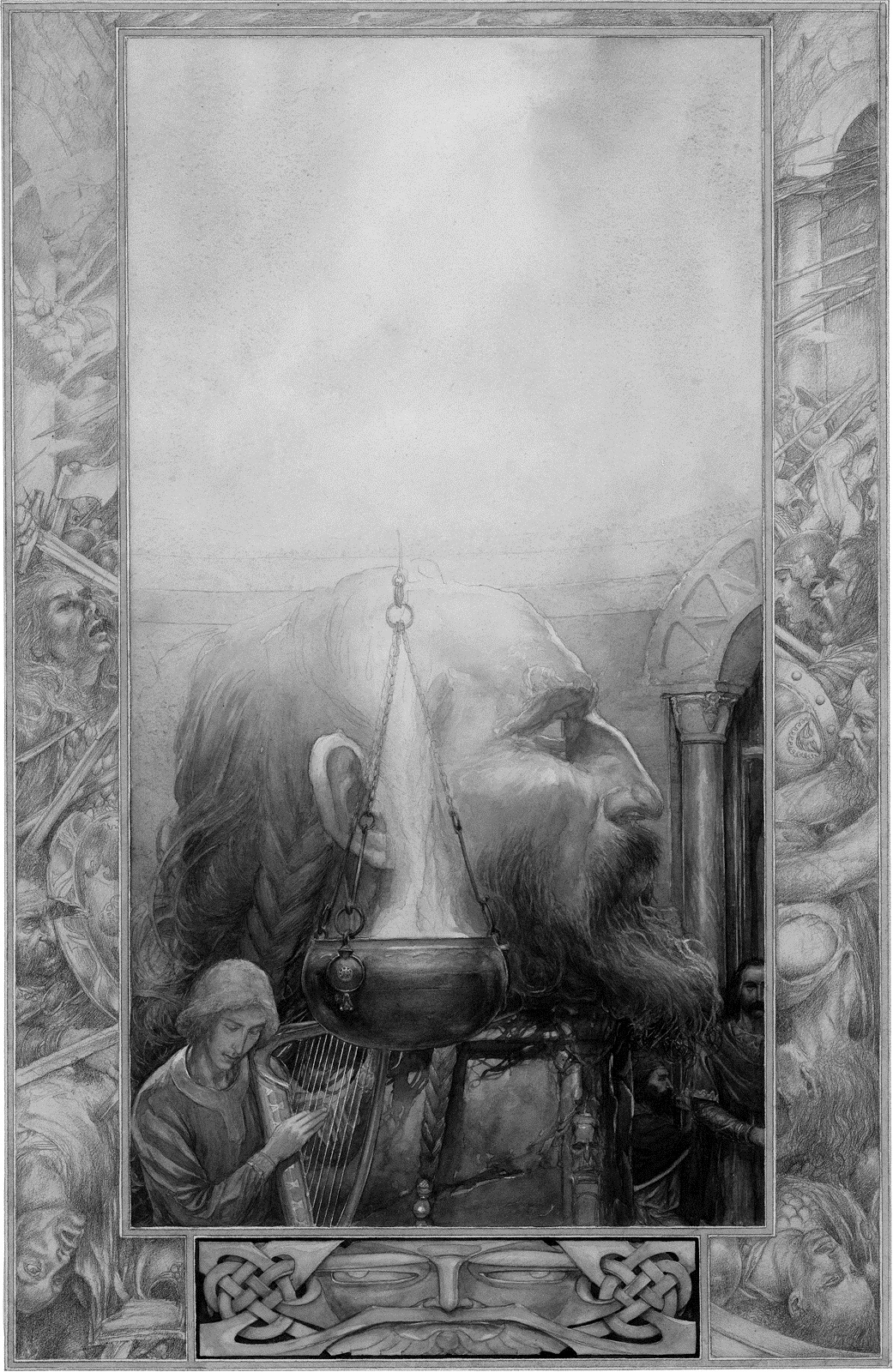

Images appear through the mist when we think of Celtic myth. A girl, face wet with dew, is summoned into being from a swirl of leaves and flowers. Colossal gods stride over a battlefield littered with broken stones. Three children flee in terror as their arms sprout feathers and become swans wings. The severed head of a giant presides over a feast, to the melodious music of far-off birds.

Such are the classic visions of Celtic mythology, a tradition superbly rich in the enigmatic and evocative. But Celtic myth is very different from the mythologies of Greece, or Rome, or India; nor does it much resemble Norse mythology. It is best approached, with expectations suspended, as a world unto itself: for us, as for many heroes in Welsh and Irish tales, there is a fall of mist, and we find we have to enter an unfamiliar world with different rules.

At one extreme, it can be argued that Celtic mythology does not in fact exist at all, and, while that is probably going too far, there is justification for keeping a pair of invisible quote marks around the term as you read this book. The reasons are as follows, and they are three in number.

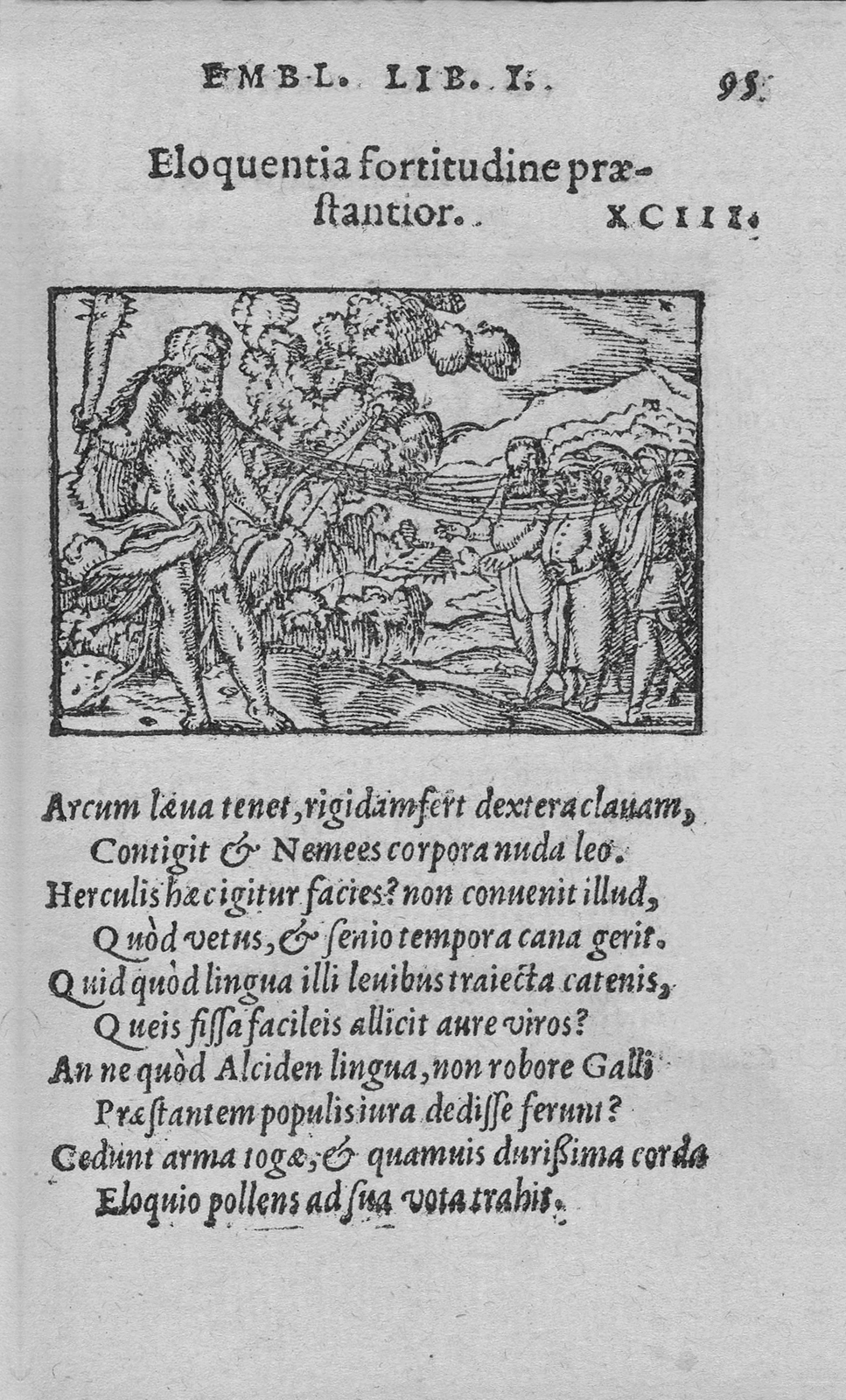

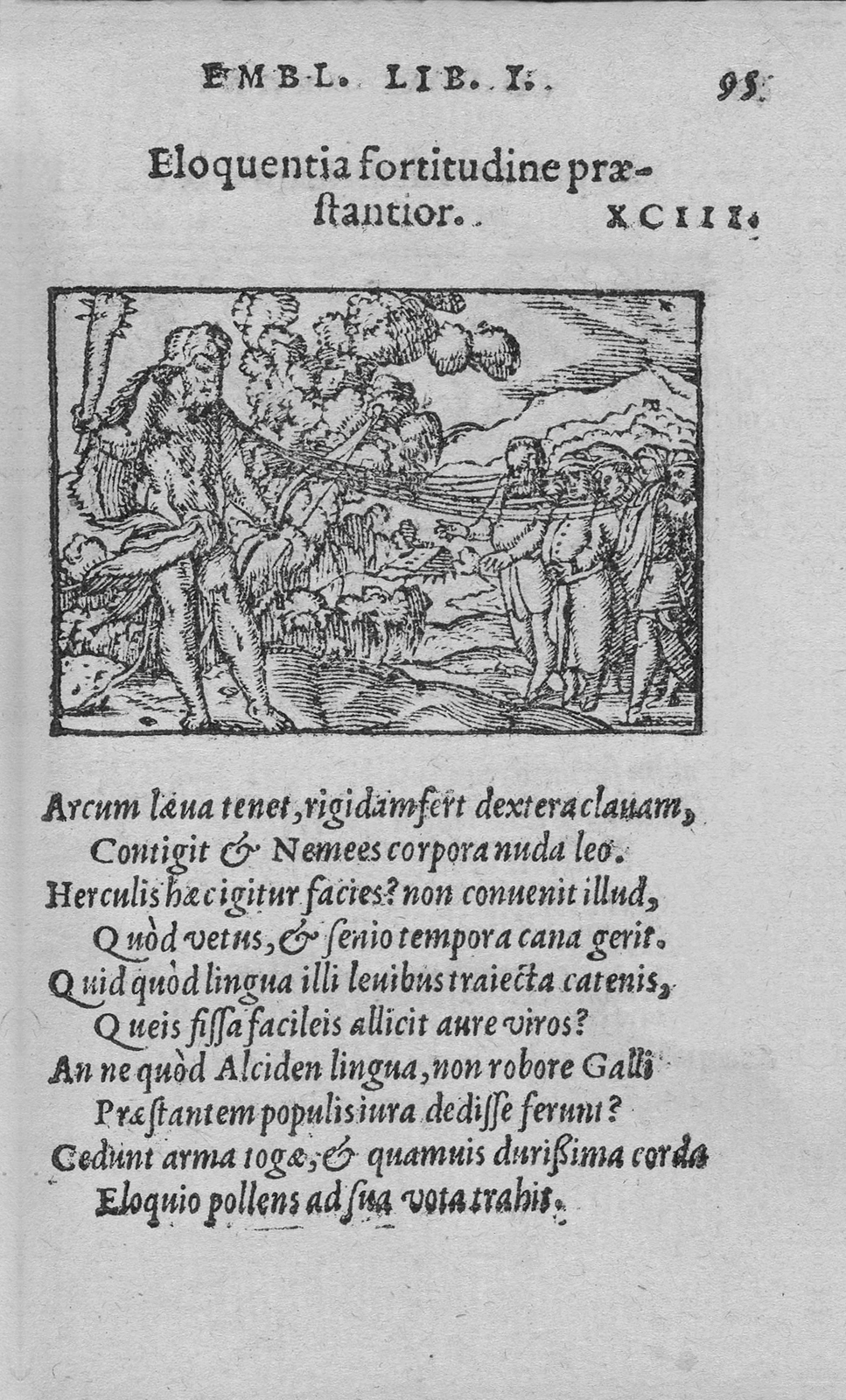

The first reason is that myth typically refers to stories about pre-Christian gods and goddesses when we are talking about Europe, at least. This is what we clearly mean when we discuss Greek myth, for example. The trouble is that all Celtic myth is a product of the Christian era: the apparently mythological stories that we possess were all written down in the Middle Ages, or even later. This means that, in stark contrast to the Greek and Roman myths, we have no versions of archaic Celtic stories as they were told by people who actually venerated the ancient divinities before the arrival of Christianity. This is not of course to deny that the ancient Celtic-speaking peoples had rich mythologies: they must have done. It is simply that we do not possess them because they did not write them down or if they ever did, those accounts did not survive. Little hints in the writings of Greek and Roman authors suggest what we have lost. To take one example, in the 2nd century AD the satirist Lucian recorded that the Gauls a Celtic-speaking people in what is now France had their own outlandish version of the demigod Heracles (the Roman Hercules). To the Gauls, Heracles was not a muscle-bound strongman, but a wrinkled, elderly figure leading a troop of followers with lengths of chain that linked his mouth to their ears a symbol, Lucian tells us, of the spellbinding power of eloquence, more often found in the old than the young. Lucian was following the convention whereby classical writers would refer to a barbarian god by the name of the nearest Greek or Roman equivalent: there is evidence that the name of this Gaulish Heracles was actually Ogmios.

William Faithorne, Lucian of Samosata, 1664.

Illustration of Hercules from Andrea Alciati, Emblematvm clarissimi viri D. Andre Alcati, 1567.

There are certainly resonances between this anecdote and some details in medieval Irish literature which has a rather similar strongman figure named Ogma but they are hard to interpret. In the absence of substantial written evidence from pre-Christian Celtic-speaking cultures about their myths, we are blind. We have material evidence, in the form of objects and ritual deposits, and while these can tell us stories about ancient peoples beliefs and behaviour, they cannot give us their myths. For that, we need writing.

As noted above, the writings that may contain some elements of Celtic myth all date from the Middle Ages, and so discussing Celtic mythology intrinsically means discussing medieval literature. One of the most important aims of this book is not only to explore what Celtic mythology is (and is not), but also to introduce and contextualize the medieval literatures of Ireland and Wales, within which that mythology is largely contained. It helps that those literatures are astonishingly rich, packed with vivid characters and dramatic plots.

The second reason why Celtic myth is a problematic term is that the Celtic is neither singular nor easy to pin down. Celtic is best used as a linguistic label, referring to a set of related languages that have distinctive features in common, and then by extension to the cultures belonging to the peoples who spoke those languages. The two most crucial cultures for the purposes of this book are those of the medieval Irish and Welsh. This is absolutely not to deny that Gaelic Scotland, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man have important traditions of their own, but the literatures of Wales and Ireland are so rich that I cannot treat even those as fully as I might wish in a short book such as this. They are also early, as these things go: the earliest Irish mythological material, for example, probably dates to the 700s AD. But it must be remembered that the Irish and Welsh traditions are essentially separate: there are certainly points of contact, and the older forms of the Irish and Welsh languages benefit from being studied comparatively (this is in fact the foundation of the academic discipline of Celtic Studies), but they are not the same. We should really therefore be speaking of Celtic mythologies, in the plural.

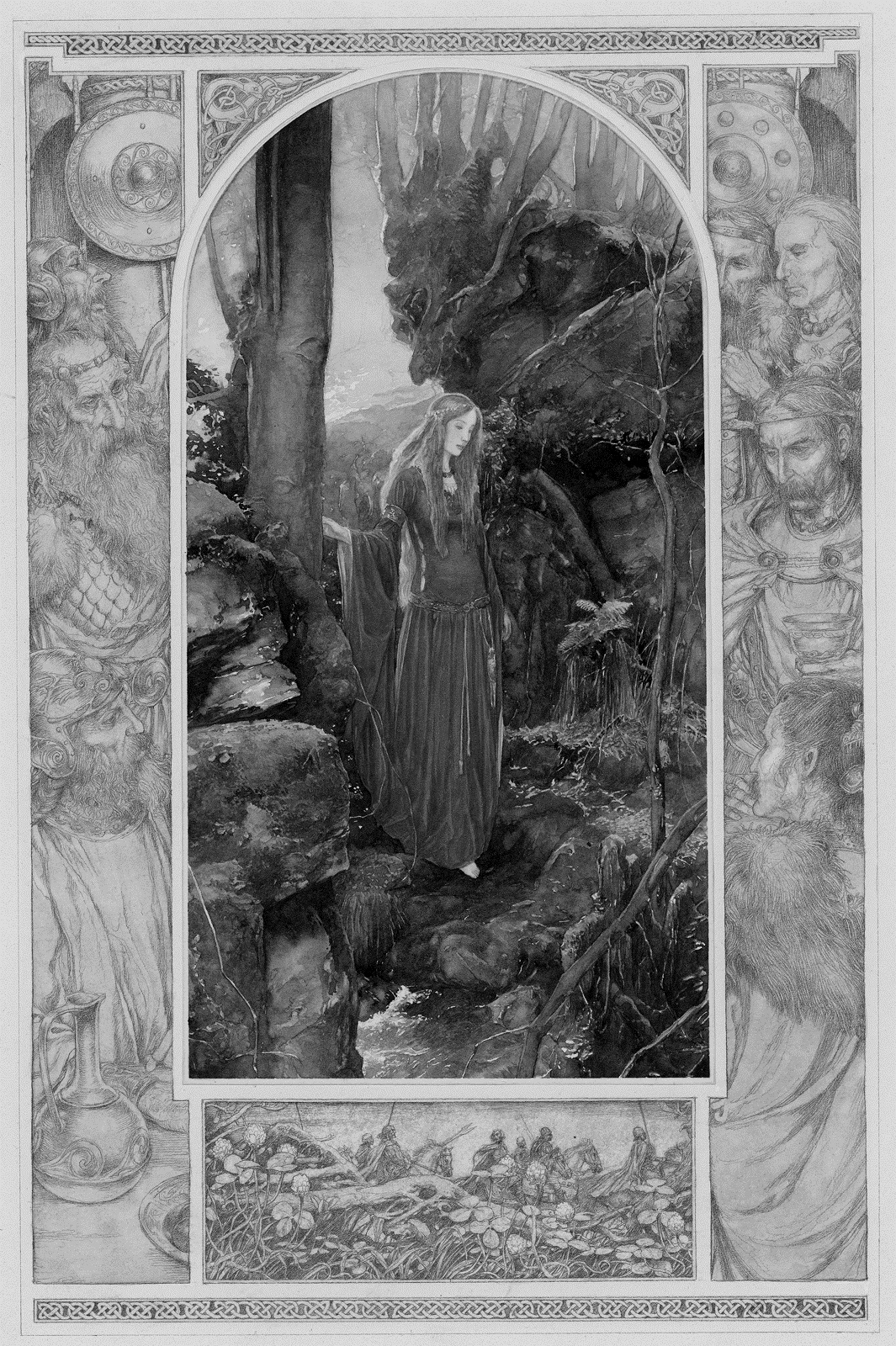

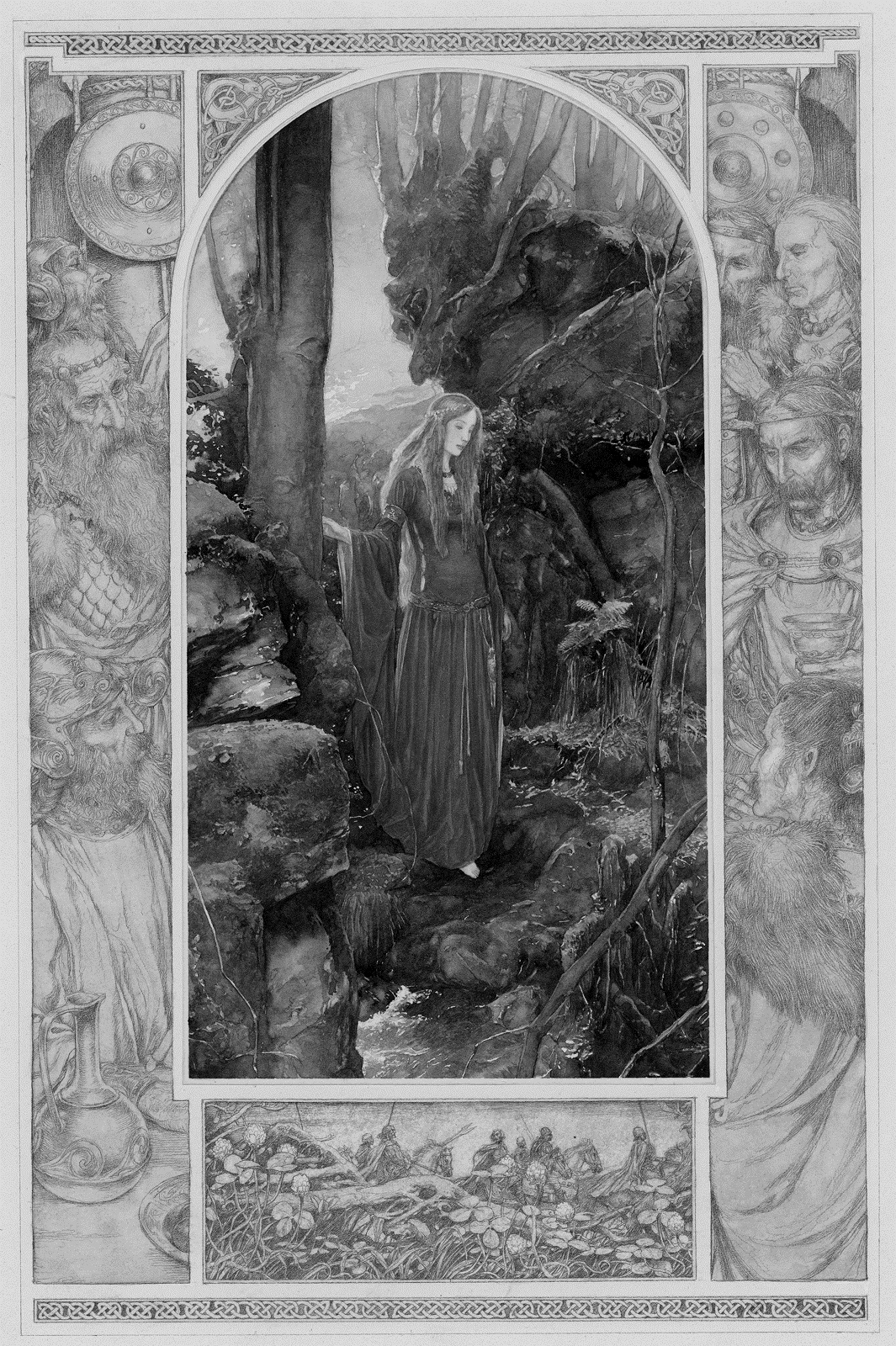

Alan Lee, Brans Head, 1982: the severed but still living head of the giant Bran the Blessed presides over an otherworldly feast.

The third reason why the term Celtic mythology is tricky is that, for more than two centuries, many writers and artists have found the idea of a wellspring of Celtic legend and tradition deeply appealing, and in some cases profitable. The English-speaking world undergoes occasional spasms of enthusiasm for Celtic things, and writers in English have repeatedly turned to the medieval sources and reimagined them in ways that suited their own creative purposes. This means that Celtic mythology is especially rich in what scholarly jargon terms afterlife, and here a comparison with classical myth may be helpful. Most classical myths lets choose the story of the poet Orpheuss loss of his wife, Eurydice also have a rich afterlife. That story, of the poet who rescues his dead spouse from the world below only to lose her again at the last moment, has been adapted and retold in countless different languages and in many different media, from medieval romance (

Next page