Women, Mysticism, and Hysteria in Fin-de-Sicle Spain

Women, Mysticism, and Hysteria in Fin-de-Sicle Spain

JENNIFER SMITH

Vanderbilt University Press

Nashville

Copyright 2021 Vanderbilt University Press

All rights reserved

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Jennifer, 1970 November 13 author.

Title: Women, mysticism, and hysteria in fin-de-sicle Spain / Jennifer Smith

Description: Nashville : Vanderbilt University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index

Identifiers: LCCN 2020056887 (print) | LCCN 202005 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826501875 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780826501868 (paperback) | ISBN 9780826501882 (epub) | ISBN 9780826501899 (pdf)

Subjects: WomenSpainSocial conditions19th century | WomenSpainSocial conditions20th century | MysticismSpainHistory | Women mysticsSpainHistory | HysteriaSocial aspectsSpainHistory | FeminismSpainHistory.

Classification: LCC HQ1692 .S596 2021 (print) | LCC HQ1692 (ebook) | DDC 305.40946dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056887

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056888

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WOULD LIKE to express my deepest gratitude to Denise DuPont, Vronique Maisier, Nicholas Wolters, and the outside readers for Vanderbilt University Press, for generously offering their time and expertise to read earlier drafts of the book and give insightful feedback. I would like to thank Catherine Jagoe for her help in the early stages of this project when she generously shared many of her materials with me. Thanks to Lourdes Albuixech and Vronique Maisier for their assistance with translations from Spanish and French, and Francisco Vzquez Garca for sharing an electronic copy of one of his books when the university libraries in the US were shut down due to COVID.

Thanks go to Revista de Estudios Hispnicos and Decimonnica for permissions to reprint previously published material. Financial support for early research for this project came from the Program for Cultural Cooperation between Spains Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports and United States Universities and from the Timothy J. Rogers Fellowship Foundation. The time needed to complete this project was made possible by sabbatical leave granted by Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Finally, I would also like to thank my husband, Shawn, and daughter, Francesca, for their love and support.

INTRODUCTION

ON JANUARY 23, 1836, Doa Mara de los Dolores Quiroga, more commonly known as Sor Patrocinio, was detained and charged with faking divine favors in order to aid in the subversion of the state by Prince Don Carlos and his followers.the Catholic segments of society that supported the modern-day saint in the hopes that she would strengthen a Church that was under fierce political attack, and on the other hand, the secular scientists, doctors, and liberals who wanted to weaken the political power of the Church.

Although fraud was the main charge brought against mystics in cases such as Sor Patrocinios, what civil authorities really sought was to discredit these women and weaken what they perceived to be a political threat.

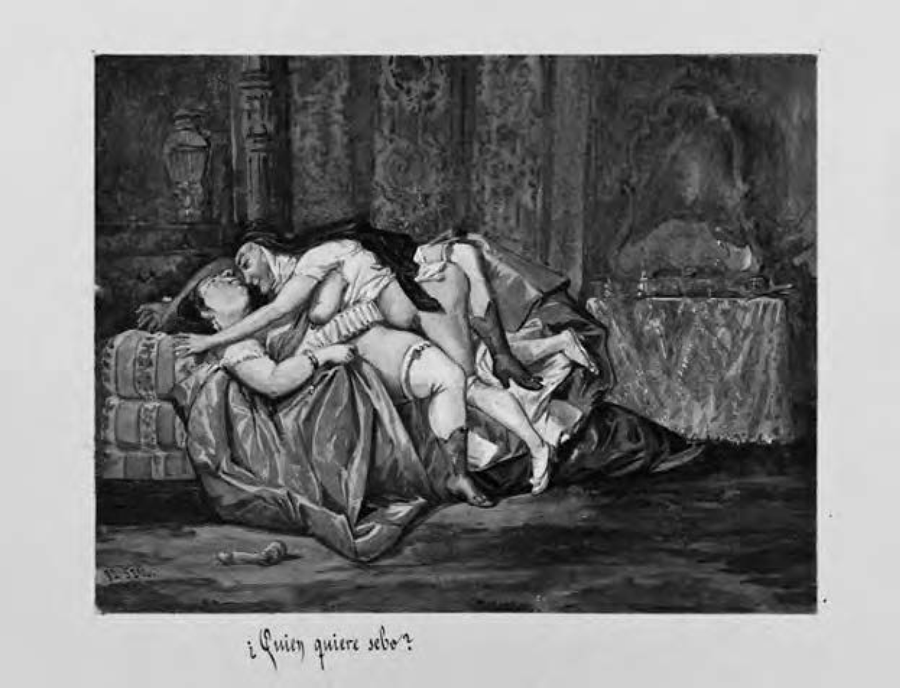

The Republican press, largely through satire and caricature, also played a pivotal role in discrediting such women. According to Andrea Graus, Anticlerical and Republican caricature used [Sor Patrocinios] image to warn of the dangers of the clergy ruling the state. She [... ] became an icon of absolutism and the struggles this image serves as a pictorial example of the way female mystics were discredited through their explicit sexualization in medical and literary texts of the time.

FIGURE 1. Quin quiere sebo? (1868; Who wants some lard?) by SEM from the collection Los Borbones en pelota (1868; The Bourbon dynasty in the nude). http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000180846. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Nacional de Espaa (The National Library of Spain).

Indeed, the specific aim of this book is to show that the reinterpretation of female mysticism as hysteria and nymphomania in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Spain was part of a larger project to suppress the growing female emancipation movement by sexualizing the female subject. I argue that we see this phenomenon in medical, social, and literary texts, and that despite many liberals hostility toward the Church, the techniques secular doctors and intellectuals employed to discredit female mystics have striking similarities to the ways the Spanish Inquisition reinterpreted female mysticism as sexual deviance and demonic possession in order to discredit powerful women. I also argue that we can better understand mysticisms subversive potential in terms of the patriarchal order by examining the writings of Emilia Pardo Bazn. The only woman author studied here, Pardo Bazn, unlike her male counterparts, rejected the hysteria diagnosis and promoted mysticism as a path for womens personal development and self-realization.

The first two chapters are historical in scope and explore the cultural fascination with mysticism and hysteria in women primarily in medical, social, and philosophical writings of the time. The first chapter contextualizes the topic by exploring Spanish medical discourses on women to reveal how the hysteria and nymphomania diagnoses, as well as the increased social pressures on couples to produce more offspring, sought to pathologize religious chastity and women who pursued a life and career outside the domestic sphere. In addition to demonstrating how the hysterization of the female body operated in Spain in the nineteenth century, this chapter shows how two other Foucauldian strategies not specifically concerned with womenthe psychiatrization of perverse pleasure (in the form of nymphomania, masturbation, and female same-sex desire) and the socialization of procreative behaviorwere also involved in the construction of a female subject naturally unable to assume the same rights and freedoms as men. This investigation also reveals European, and specifically Spanish, precedents for Sigmund Freuds theory of female sexuality. It becomes clear that Freuds idea that normal women only find pleasure in sexual acts that lead to reproduction was merely a unique reconfiguration of a variety of nineteenth-century medical assertions.

Drawing parallels between the early modern period and the late nineteenth century, argues that nineteenth-century doctors and intellectuals attempted to discredit mysticism in order to undermine one of the few existing models of female emancipation. Indeed, prominent figures such as Santa Teresa de Jess continued to attract the attention and admiration of the general public at the turn of the century. Yet, by reinterpreting religious ecstasy as disease or sexual deviance, many doctors and intellectuals were able to impose their restrictive conceptions of female identity that insisted womens biology confined their sphere of influence to the home. This chapter looks at texts such as Ramn Len Mainezs Teresa de Jess ante la crtica (1880; Teresa de Jess, in the face of criticism), Eduardo Zamacoiss medical treatise El misticismo y las perturbaciones del sistema nervioso (1893; Mysticism and disturbances of the nervous system), and the 1907 Spanish translation of Auguste Armand Maries