Table of Contents

Landmarks

For Pauline, Daniel, Honor, Finn, and Samuel

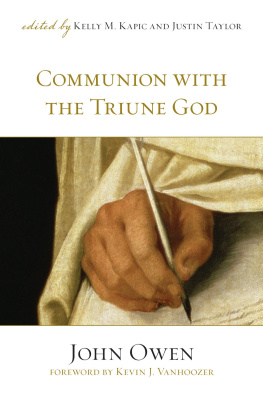

In his early twenties, shortly after abandoning his plans for a university career, and perhaps during the long period of depression that predated his conversion, John Owen read a book that left a lasting impression on his mind. He must have borrowed this copy of Henry Scudders The Christians Daily Walk (1627), which was one of the best-selling and most frequently reprinted Puritan devotional manuals, for he did not return to the work for another thirty years. When he did read the work for a second time, to prepare a commendatory preface for its eleventh edition, which appeared in 1674, his appreciation of Scudders work had only increased. Owen a devotional tool to nurture spiritual life.

Owens recollection of the impact of Scudders work provided him with tools for his own preaching to young adults. For if Owens theology of childhood was focused on initiation, nurture, and theological instruction, in ministering to young people he emphasized the same issues of piety and spirituality that he had found so affecting in The Christians Daily Walk . While speaking to and writing for young people, Owen, like Scudder, abandoned the habits of The fruit of Owens ministry to young adults was the reimagined and reenergized Calvinism that shaped his most enduring literary contributions.

Owen had occasion to think carefully about the spiritual needs of young people, for during the 1650s, he spent much of his ministry preaching to Oxford undergraduates. Enrollment was at its peak in the early seventeenth century, when matriculations at Englands two universities suddenly expanded. Many of those to whom Owen preached would have been in their mid- to late teens. Their experience would have corresponded to his own, for, little more than three decades previously, Owen had arrived in Oxford at age twelve, along with his slightly older brother, to begin undergraduate studies. He appears to have been an active and energetic young man, who, one of his friends recalled, enjoyed athletics and other sports but who was also intensely serious about his studies. It was during this period that Owen established a sustained habit of sleeping for around four hours each night. His pattern of sleep was part of a self-imposed disciplinary regime that was enabled by diligent time management and that facilitated his greediness of study.

His formation in the classics took place in the context of a bitter theological contest, as his teachers in the Queens College divided between those who favored the teaching established during the English Reformation and those who preferred the liturgical innovations that had been introduced by the universitys new chancellor, the recently appointed bishop of London, and future archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. This division was attended by at least the threat of violence among the fellows of the Queens College. It was a dangerousand stimulatingtime to pursue a theological education.

And further lessons in the gospel were to follow. Leaving the university for a precarious situation in the capital, Owen was converted, not through the teaching of Oxford fellows but through the ministry of an unknown preacher standing in at short notice for one of Londons pulpit celebrities. Owens university experience was in some sense a missed opportunity. For all his learning, his greatest discovery was not an idea but an experience. Owens new birth and early spiritual formation took place in cheap lodgings in London and with the help of a borrowed book.

Oxford had shown Owen that anyone could become a theologian. But his experience in London had persuaded him that true believers could be distinguished from false professorsand that true believers were distinguished not by what they knew but by how that knowledge made them feel and by what those affections made them do. An emotional and volitional response to the gospel was critically important. True conversion involved the will and the heart as well as the mind, and Owens ministry to students targeted those whose knowledge of the gospel was merely intellectual.

Owens Return to Oxford

Owen was a changed man when he returned to Oxford in 1651. After several years of parish ministry, the cultivation of several well-placed patrons, and an army chaplaincy during the invasions of Ireland and Scotland, Owen reentered academic life around the age of thirty-five. He was still young enough to remember the experience of youth, the dizzying possibilities of learning, and the sense that there was more to read than there could ever be time to read it. And so, as he began his career as a professor of theology and a university administrator, Owen took opportunities to speak to undergraduates about the things that he believed should matter most. As dean of Christ Church from 1651 and as vice-chancellor of the university from 1652, Owen made strenuous efforts to inspire his young charges with a vision of godliness enabled by the Calvinism that he was beginning to reimagine.

Owens new surroundings were very familiarand so was the life of his students. He was quite aware of their potential for disruptive and occasionally riotous behavior. As college dean and university vice-chancellor, he sat on committees that considered breaches of student discipline, some of which were serious indeed. He did his best to calm the graduation ceremonies, in which students had engaged in a carnivalesque inversion of academic hierarchies and in which their behavior had spun out of control. His agenda for university reform included the pastoral care of his undergraduates, which he advanced in his teaching and preaching.

Owen took education very seriously and understood its purpose in redemptive terms. But this knowledge had been reduced after his expulsion from the garden, and it had been further dissipated by means of the division of tongues at Babel. The effect of this sudden eclipse of knowledge had been social as well as religious:

Ignorance, darkness, and blindness, is come upon the understanding; acquaintance with the works of God, spiritual and natural, is lost; strangeness of communication is given, by multiplication of tongues; tumultuating of passions and affections, with innumerable darkening prejudices, are also come upon us.

Education was about unpicking knots, he explained in a central, extended metaphor. The whole design of learning was to disentangle the soul from the effects of sin; or, as he put it more fully, the aim and tendency of literature was to disentangle the mind in its reasonings, to recover an acquaintance with the works of God, to subduct the soul from under the effects of the curse of division of tongues. Learning was a means to recover lost knowledge, the particular end of which was to remove some part of that curse which is come upon us by sin. In its ideal form, education was meant to be redemptive, an enabler of the spiritual life.

But, Owen recognized, education could not now fulfill this redemptive purpose, for the Education could not achieve its redemptive purpose without gracewithout the gospel.

Owens efforts at reforming the student body met with mixed success. His college community was home to many gifted students, including some who would be among the most famous names in the cultural life of the later seventeenth century. Some students in Christ Church, including John Locke, the future philosopher, did not appreciate Owens program for their improvement; in letters to acquaintances, Locke made fun of his college dean. The resistance of other students was more overt: on at least one occasion, a large party from Christ Church invaded another college and wreaked havoc.

Alderseys notebooks offer a rare glimpse into the kinds of preaching that the Oxford students could hear. In his first year of studies, Aldersey was attending sermons by a range of preachers, including Oxford academics such as the two Henry Wilkinsons, respectively the canon of Christ Church and principal of Magdalene Hall; John Wilkins, warden of Wadham College; and the Presbyterian minister and Westminster Assembly member Edward Reynolds. While they were all sympathetic to the theology and piety of the Calvinist Reformation, they had very different views of church order, came from different sides in Oxfords culture war, and nursed personal rivalries to boot. Reynolds, for example, had been dean of Christ Church until he had been ousted by a committee that wished to appoint Owen in his place, and Reynolds in turn would replace Owen after he fell out of favor with the Cromwell family at the end of the decade. Despite these sometimes serious differences, these men shared a common outlook on Christian faith and behaviorbut, as Alderseys notebooks suggest, not many of them were able to present Reformed theology with Owens imagination.