First published in 1998

by Curzon Press

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1998 Historical Foreword, Alex McKay

1998 Editorial Matter, Peter Richardus

Typeset in Times by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-0-700-71023-2 (hbk)

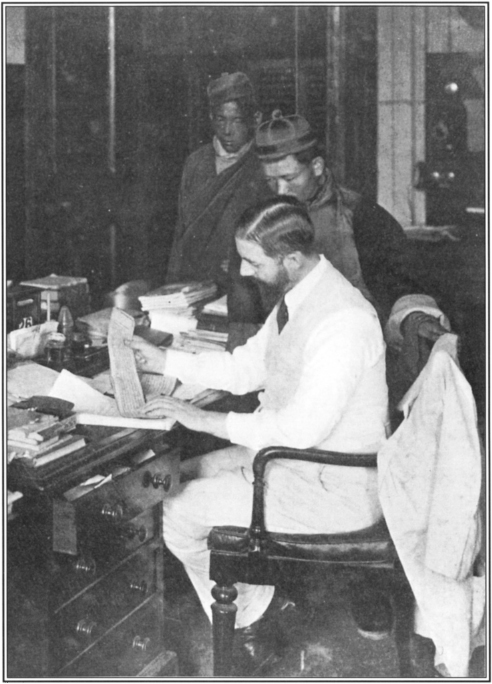

Frontispiece M.A.J. van Manen reading a Tibetan Buddhist text in his office at the Calcutta-based Asiatic Society of Bengal, c.1924.

Phun-tshogs Lung-rtogs, c.1923.

sKar-ma Sum-dhon Paul alias sKar-ma Babu, c.1923.

Tsan-chih Chen, c.1923.

Tsan-chih Chens family portrayed in front of an altar decorated by way of auspicious texts. The author, still a young boy, stands to his fathers left. His mother is flanked by her three daughters. The Chinese characters include the expression of the familys desire to uphold traditional virtues such as harmony, faith and honesty.

Tsan-chih Chen in the classroom learning to read and write. The text on the altar reads: The great, perfect saint and our tutor Confucius.

The Amban, the Chinese representative at lHa-sa, officially requests Tsan-chih Chens father to present gifts to the Pan-chen bLa-ma. The Chinese characters may be translated: Faith, reliability and deep respect.

The Pan-chen bLa-ma receives Tibetan Buddhist ritual objects, silver and rolls of silk: all presents from the Chinese government.

The newly-wed Lei and Shu-chen stand in front of an altar dedicated to the ancestors. The inscriptions aim at invoking a happy marriage. Tsan-chih Chen lights crackers to scare off any evil.

Tsan-chih Chens father is ceremoniously escorted to his last resting place, a Chinese cemetary.

Tsan-chih Chen, kneeling in the Manchurian manner, is appointed to the post of translator at the Sino-Tibetan Translation Department.

The Amban offers incense to a Tibetan Buddhist deity in the Jo-khang.

The Amban returns to his quarters seated in a palanquin.

Traditional Chinese festivities taking place on New Years Day. The hand held sign reads Peace on earth.

Tibetan officials consult the oracle of lHa-sa.

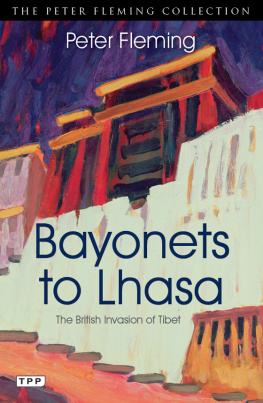

Tibetan officials cast spells in order to expel Anglo-Indian invaders.

Anglo-Indian troops parade before the Potala, lHa-sa.

Flight of the Ta-lai bLa-ma to Peking.

The Ta-lai bLa-ma visits the Emperor and Dowager Empress of China.

The monks from Ba-tang massacre Chinese officials.

Chinese officials pray before the Imperial Tablet.

Chinese troops in combat against Tibetan soldiers.

Po-pas ambushing a silver transport in the province of Khams.

Tsan-chih Chen takes leave at the rDo-rje-gling Railway Station.

Tsan-chih Chen teaches at the Tibetan Mission, rDo-rje-gling.

sPyan-ras-gzigs, the Eleven-headed God of Mercy.

Tsan-chih Chen worshipping Sakyamuni Buddha at the Jo-khang.

King Srong-brtsan sGam-po, who introduced Buddhism to Tibet, in the company of his two wives.

dPal-ldan lHa-mo, the female tutelary deity of lHa-sa.

The Potala, lHa-sa with two large hangings unrolled between 5 and 18 April 1901.

The monastery of Se-ra, c.1900.

The monastery of Bras-spungs, c.1900.

The monastery of dGa-ldan, c.1900.

The monastery of bKra-shis-lhun-po, c.1900

Historical Foreword

In the early years of the twentieth century, control over Tibet was contested by three major empires, those of China, Russia, and Britain. The imperial powers and those who came in their wake missionaries, scholars, traders and soldiers employed local staff to assist in their dealings with the Tibetans. These employees had a crucial role in Tibets encounter with the outside world. Yet they have been largely forgotten by history and most of the knowledge and understandings which they gained has been lost.

It was left to a Dutchman, and hence an outside observer of the British imperial system, to preserve the impressions of three of those who served on the periphery of the imperial process. The three vignettes that make up this work offer a unique insight into the world of the intermediary class. In addition to their entertainment value, they are an important contribution to our understanding of the history of Tibet and its encounter with the outside world.

To fully appreciate what follows, we must first understand a little of the background to these accounts, for they presume a knowledge of Tibetan history and culture. A recognisable Tibetan state first emerged in the seventh century of the Christian era, when tribal groups united under the rule of a king called Srong-brtsan sGam-po (60549/50 A.D.), who extended the power of his Yar-klungs dynasty over most of the Tibetan-speaking world. To the period of his rule is attributed the introduction of Buddhism, although the influence of the new religion was initially confined to court circles. Srong-brtsan sGam-pos successors, however, increasingly turned to Buddhism at the expense of the existing belief system, an early form of the Bon faith which subsequently developed a close association with Buddhist beliefs and practises.

The initial introduction of Buddhism into Tibetan society was associated with the activities of an Indian Tantric master, Gu-ru Rin-po-che, who was invited to Tibet by a king called Khri-srong lDe-brtsan: 742-c.97). Although a historical personage, Gu-ru Rin-po-che became a legendary figure, who in the Tibetan understanding used his magical powers to subdue the forces of the Bon-po and establish Buddhism as the dominant faith in Tibet.

In the political sphere, Yar-klungs dynasty Tibet became a powerful Central Asian empire. Its forces ranged as far west as Samarkand, and in 763 they sacked and briefly occupied Changan (present-day Xian), the capital of Chinas Tang empire. Internally, however, Tibet was far from unified during this period. There were frequent local revolts against central authority. The competing interests of aristocratic and religious forces culminated in 842 with the assassination of King gLang-dar-ma, the last of the Yar-klungs dynasty. The Tibetan empire subsequently collapsed, fragmenting into a series of principalities exercising purely local hegemony.