Text individual contributors as credited in each work

2020 Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited

Published in 2020 by Marshall Cavendish Editions

An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196. Tel: (65) 6213 9300 E-mail:

The publisher makes no representation or warranties with respect to the contents of this book, and specifically disclaims any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose, and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Other Marshall Cavendish Offices:

Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 800 Westchester Ave, Suite N-641, Rye Brook, NY 10573, USA Marshall Cavendish International (Thailand) Co Ltd, 253 Asoke, 16th Floor, Sukhumvit 21 Road, Klongtoey Nua, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Times Subang, Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Marshall Cavendish is a registered trademark of Times Publishing Limited

National Library Board, Singapore Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Names: Cheong, Felix, editor.

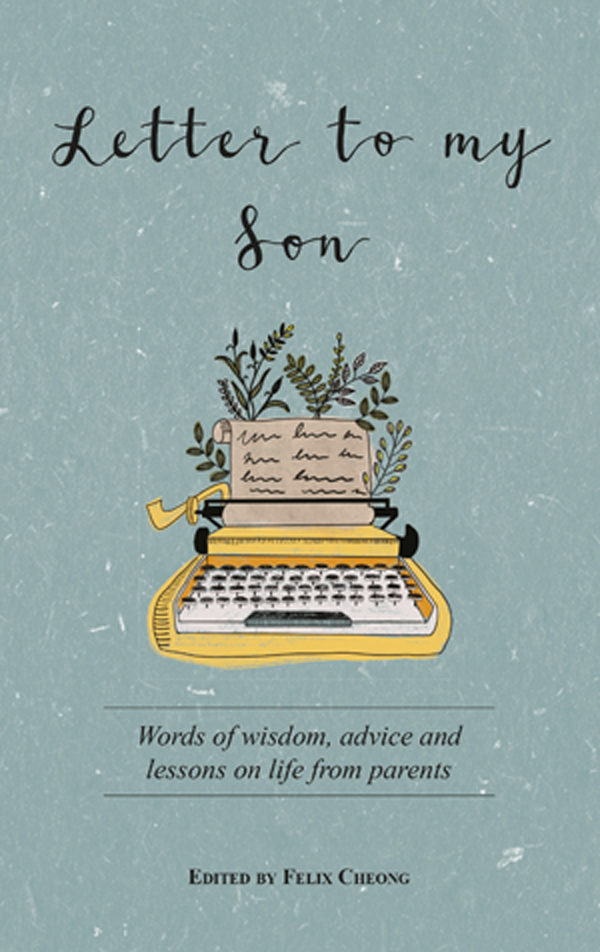

Title: Letter to my son : words of wisdom, advice and lessons on life from parents / edited by Felix Cheong.

Description: Singapore : Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2020.

Identifiers: OCN 1184758487 | e-ISBN 978 981 4928 32 8

Subjects: LCSH: FathersCorrespondence. | MothersCorrespondence. | Parent and child. | MenConduct of life.

Classification: DDC 306.8742dc23

Printed in Singapore

Cover design by Adithi Khandadai

This book is dedicated to all parents, in the hope that these shared experiences will inspire and shape your own parenting journey.

Contents

FELIX CHEONG

DINESH RAI

CHRIS HENSON

DARREN SOH

OLIVIER AHMAD CASTAIGNDE

MARK LAUDI

ANITHA DEVI PILLAI

LESTER KOK

P N BALJI

NIZAM ISMAIL

CLEMENT MESENAS

BERNARD HARRISON

KENNY CHAN

GILBERT KOH

ROLAND KOH

CHRISTOPHER NG

VICKY CHONG

ANTHONY GOH

DANIEL YAP

FONG HOE FANG

SANJAY C KUTTAN

Foreword

Felix Cheong

What cannot be said sometimes has to be written down.

On paper, emotions can be contained, measured within margins, fed line by line to the reader. That discomfort of saying exactly what you mean, without the hedge of filler words, is quarantined, for a time at least, between periods.

You can re-read the words, relish the will it had taken to bring them to pen, and remember them fondly afterwards.

That was what I feltand still dowhen I first read my fathers final words. I could not have known then, in mid-December last year, that those little notes he had scribbled in bed would be something of a letter to my three brothers and me.

Two days into his admission for pneumonia at Changi General Hospital, Dad was robbed of his voice. His breathing was laboured; the oxygen level in his lungs had dropped dangerously to 60 per cent, a critical beat away from collapse. He had to resort to writing notes to communicate with the ward staff and me.

By the end of his fifth day at the high dependency ward, he passed away. I had visited him that afternoon; his ward doctor had told me Dad was getting better and was, in fact, planning to transfer him to the general ward. But it was not to be. Talk about a false dawn.

As with men of his generation, reticence was the better part of his valour. Although Dad had, on occasion, told us he loved us, he had never written down anything that could pass as life lessons, his manual on how best to lead your life. I recall he had written me a few aerogram letters when I was living in Brisbane between 2001 and 2002. But the content was all reportage, with little insight on the cards that life had dealt him and how he played them.

Dads last scribbles did, however, contain some lessonsor so I would like to believe. Although his handwriting, which I used to admire for its cursive flourishes, was unsteady and staccato-like, I could still discern between the lines what he was trying to put across.

In two instances on separate dayswritten on the reverse side of recycled paperhe referred to God. He and Mum were staunch Catholics. Mum was in the same hospital at the same time with pneumonia and died three weeks after Dad.

I will go in peace the Lord, one note said. Another note said: I am old if God will I will (indecipherable). (The word looks like have but in this context, does not quite make sense.)

In essence, if I could percolate a lesson from these words: Put your life in the hands of God. If it is His will, He will lead you down His way. That philosophy gels with what I know of Dad: Trust that what the Lord hath giveth, He will know when it is time to taketh.

In two instances, he talked about Mum. In one note, he wrote: Mum might be discharge 2/3 days. How to tell her. She cried every day. Please look after her.

Another note said: Dont Mother. Dont Mother nothing serious. From the context, it is clear the missing word here is tell.

(Following Dads wishes and a mini-conference among ourselves, we kept the news of his hospitalisation from Mum, lest she be so distraught that it affected her recovery. We merely told her he was down with a bad cough at home. Our strategy backfired when he died without the two of them seeing each other again. Mum would lament this all the way to her death. After all, they were married for 57 years.)

Here, I am guessing what his parting (or departing) shot was: Do not let your loved ones know the bad news, especially when they might not be in a state to receive it.

I am not sure if necessity should be the mother of invention of half-truths. Given my hindsight now that keeping the news from Mum had not made her any better but, in fact, might have weakened her emotionally, I would have let them meet, many times over, in their last days.

A few notes Dad dashed off had to do with money. First, he revealed the PIN for his ATM card. Then, in two instances, he referred specifically to our Indonesian domestic helper, Arini. Arini is running short of money. $300 for her, said one note. Another said: Give $100 for Arini expenses.