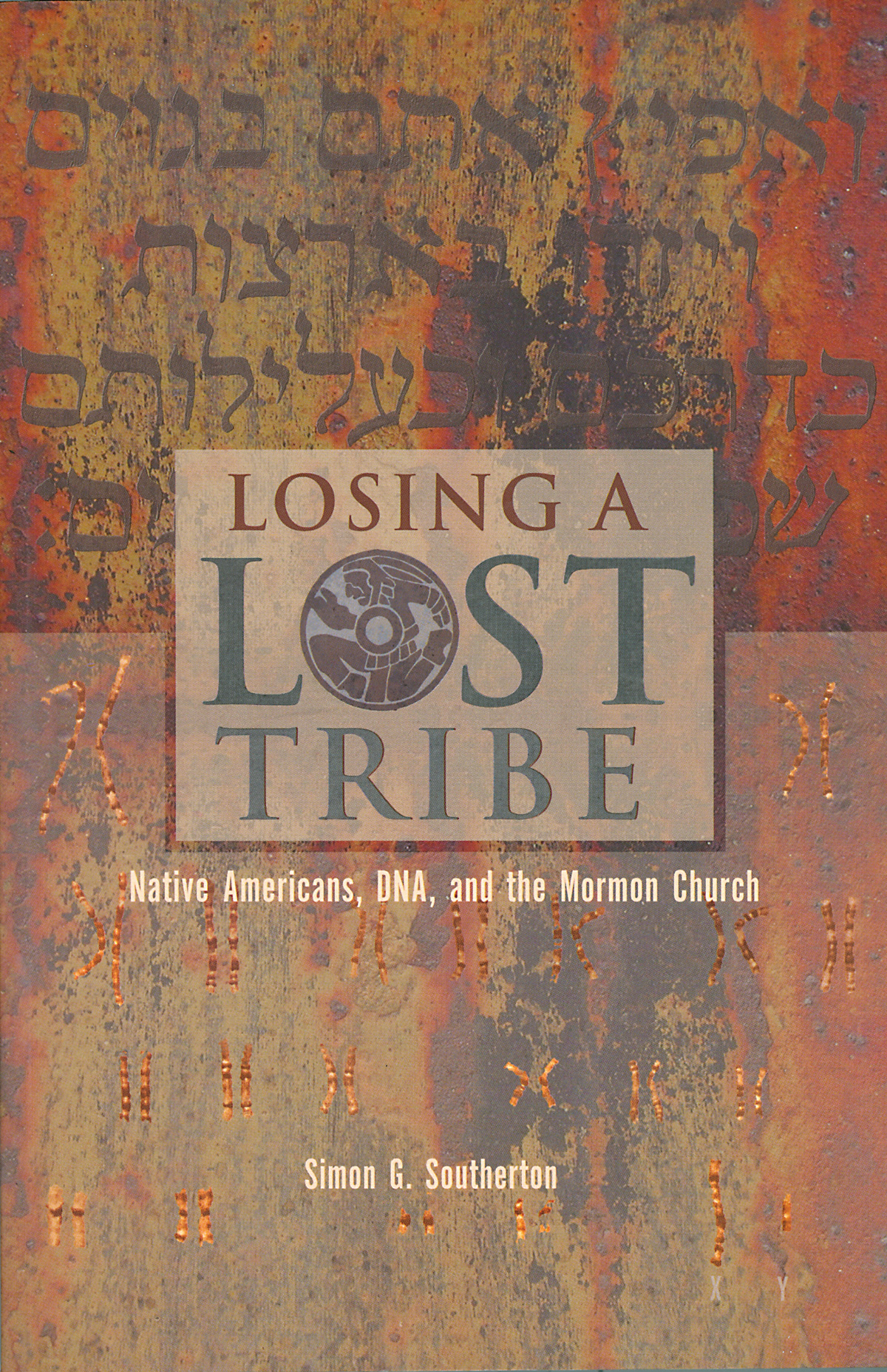

Losing a Lost Tribe

Native Americans, DNA, and the Mormon Church

Simon G. Southerton

Signature Books | Salt Lake City | 2004

S imon G. S outherton is a senior research scientist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) in Canberra, Australia. He is a former senior research scientist in the Department of Biochemistry, University of Queensland, and post-doctoral fellow at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, England. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Sydney in plant science and now specializes in the molecular biology of forest trees. He has published research articles in international journals such as Plant Molecular Biology, Plant Physiology, and Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. He served an LDS mission to Melbourne in the 1980s.

Cover design: Julie Easton

Copyright Signature Books 2004. All rights reserved. Signature Books is a registered trademark of Signature Books Publishing, LLC.

See: http://www.signaturebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Southerton, Simon G.

Losing a lost tribe : Native Americans, DNA , and the Mormon Church / by Simon G. Southerton.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN: 1-56085-181-3 (pbk.)

1. Book of Mormon. 2. IndiansOrigin. 3. Lost tribes of Israel. I. Title.

BX8627.S647 2004

289.32dc22

2004052191

Contents

Introduction

And thy seed shall be as the dust of the earth, and thou shalt spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north, and to the south: and in thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed.

Genesis 28:14

When Christopher Columbus launched into the Sea of Darkness over 500 years ago, his intention was to find a quick route from Spain to the riches of the Indies. Relying upon Ptolemys (AD 90-168) maps of a spherical earth bearing only the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa, Columbus was certain he had achieved this goal when he landed in the Bahamas in 1492. It was about where he had expected the Indies to be. All his life he stubbornly refused to accept that he had discovered a new continentthe world he knew having had no room for a western hemisphere. His error was due to calculations of the earths circumference that made the earth a quarter too small. Centuries later, Europeans came to grips with the geography of the quarter of the earth that had eluded Ptolemys pen. This miscalculation lives on in the popular misunderstandings about the origins and diversity of native people who inhabit that geography.

Europeans were at first mystified by the presence of people at such great distances from the centers of civilization that were familiar to the Judeo-Christian world. Not surprisingly, early attempts to account for their origins were ensnared in the biblical mindset, the widely accepted worldview among members of the European societies that emerged from the ashes of the Roman Empire. In many cases the native inhabitants of the Americas and the Pacific were regarded as savages, the degraded remnants of once civilized nations whose origins could be traced back to Noahs offspring. A common and persistent theory among early Europeans was that Native Americans and Pacific Islanders were the scattered remnants of the House of Israel.

For over a century, the vast majority of scholars and scientists have been satisfied that Native Americans and Pacific Islanders share a common ancestry. But it is not in Israel. The academic world has accumulated a comprehensive library of work that links each of these groups with an ancient homeland in Asia. Most scholars now accept that the ancestors of the American Indians began migrating to the Americas from somewhere in the vicinity of southern Siberia, across an icy Bering Strait, over 14,000 years ago. Similarly convincing are the signs that the early colonizers of the Pacific Isles began emerging from Southeast Asia about 30,000 years ago. The most recent of these migrations, within the last 3,000 years, resulted in the colonization of the vast expanse of Polynesia.

Remarkably, it is among members of the Mormon church that we find some of the strongest resistance to mainstream views of New World and Pacific colonization. Not only do Mormons link Native American culture with ancient seafarers, most Latter-day Saints hold that the ancestors of indigenous Americans were Israelites, derived from small groups of immigrants who arrived hundreds of years before the birth of Christ. The Polynesians are believed to be descended from these maritime Hebrews as a consequence of further nautical excursions from their New World settlements. These beliefs are widely held among Mormons. For well over a century, such tenets have profoundly influenced church policies and played a major role in the conversion of indigenous peoples from both regions.

The staunch resistance to mainstream scientific views stems from Mormon faith in the Book of Mormon. First published in New York in 1830, it is believed by Mormons to be an American counterpart of the Bible describing the literal arrival and history of Hebrews in the New World. Joseph Smith, the prophet who brought forth the Book of Mormon, claimed the book was a direct translation from the record he said was inscribed on gold plates and buried in a hill near his home in the village of Manchester, New York. Smith said he went to the hill in 1827 and that the gold plates were delivered to him by an angel named Moroni, a prophet who had lived in America in about AD 400. According to Smith, Moroni was the last of a line of prophets who had written on the plates and the one who deposited them in what is now known as the Hill Cumorah. The Book of Mormon is considered by Mormons to contain a literal account of Gods dealings with the people who lived anciently in the New World.

According to the Book of Mormon, most of its fifteen books were collated and abridged by the penultimate prophet-historian Mormon, after whom the book is named. Those who believe in the books religious message, are, therefore, known as Mormons. The book is primarily devoted to a small group of Jews who, we are told, sailed from Jerusalem in 600 BC. The descendants of these colonists multiplied rapidly, splitting into two large nations. One nation is depicted as a culturally advanced society that was populated with a light-skinned race. The other nation was culturally inferior and was cursed by God with a dark skin. During most of the thousand-year Book of Mormon history, these light- and dark-skinned races remained in continual conflict. Eventually, the white-skinned nation descended into wickedness and was eliminated by the dark-skinned race around AD 400. It is to the descendants of the dark-skinned race that the Book of Mormon is most specifically addressed. Mormons believe that this race constitutes the principal ancestors of the American Indians.

The Book of Mormon is deeply embedded in the Mormon faith. Joseph Smith once affirmed that it was the most correct of any book on earth, a claim that has been disputed since the day it was published. He went on to state that the book was the keystone of our religion, which is undoubtedly true. The Book of Mormon was crucial to the establishment of the Mormon church. Adherents claim that if this record is true, then it follows that Joseph Smith was a true prophet of God. If Joseph Smith was a true prophet, then the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the only true church on the face of the earth because Smith said so.

While its claims may appear extraordinary today, the Book of Mormon narrative mirrors the myths that permeated the society from which the church emerged. Most American colonists held to a very literal interpretation of the Bible, including the idea that there was a rapid colonization of the earth after the Flood in 2500 BC. The most widely accepted explanation for the origin of the so-called Red Man in the New World was that they were a degraded descendant of the scattered House of Israel. Indians were blamed for having annihilated another race that was believed to have been responsible for the construction of the elaborate buildings and cultural artifacts that American colonists uncovered as they advanced westward over the Appalachian Mountains. This other race was assumed to have been light-skinned.