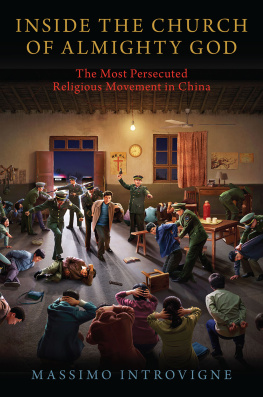

Inside The Church of Almighty God

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190089092

eISBN 9780190089115

Contents

On January 6, 2019, the day of the Epiphany in my own Catholic tradition, I was standing in a large but overcrowded apartment on Jeju Island, South Korea, hosting some forty refugees from a new Chinese religious movement, The Church of Almighty God (The is always capitalized). Jeju Island is situated midway between the coast of China and Seoul; a 2018 Korean law mandates that refugees applying for asylum must remain on the island until their application has been resolved. They are not permitted to work, so they spend their days waiting for a decision from a country where obtaining protection is difficult. All of the refugees in the apartment that day had arrived from China in 2018. Only a few of them spoke English. With the help of an interpreter, they told their stories of persecution, separation from their loved ones, and in some cases torture. They were nervous and scared, and many wept profusely. They asked only one thing: that their stories be told to the world.

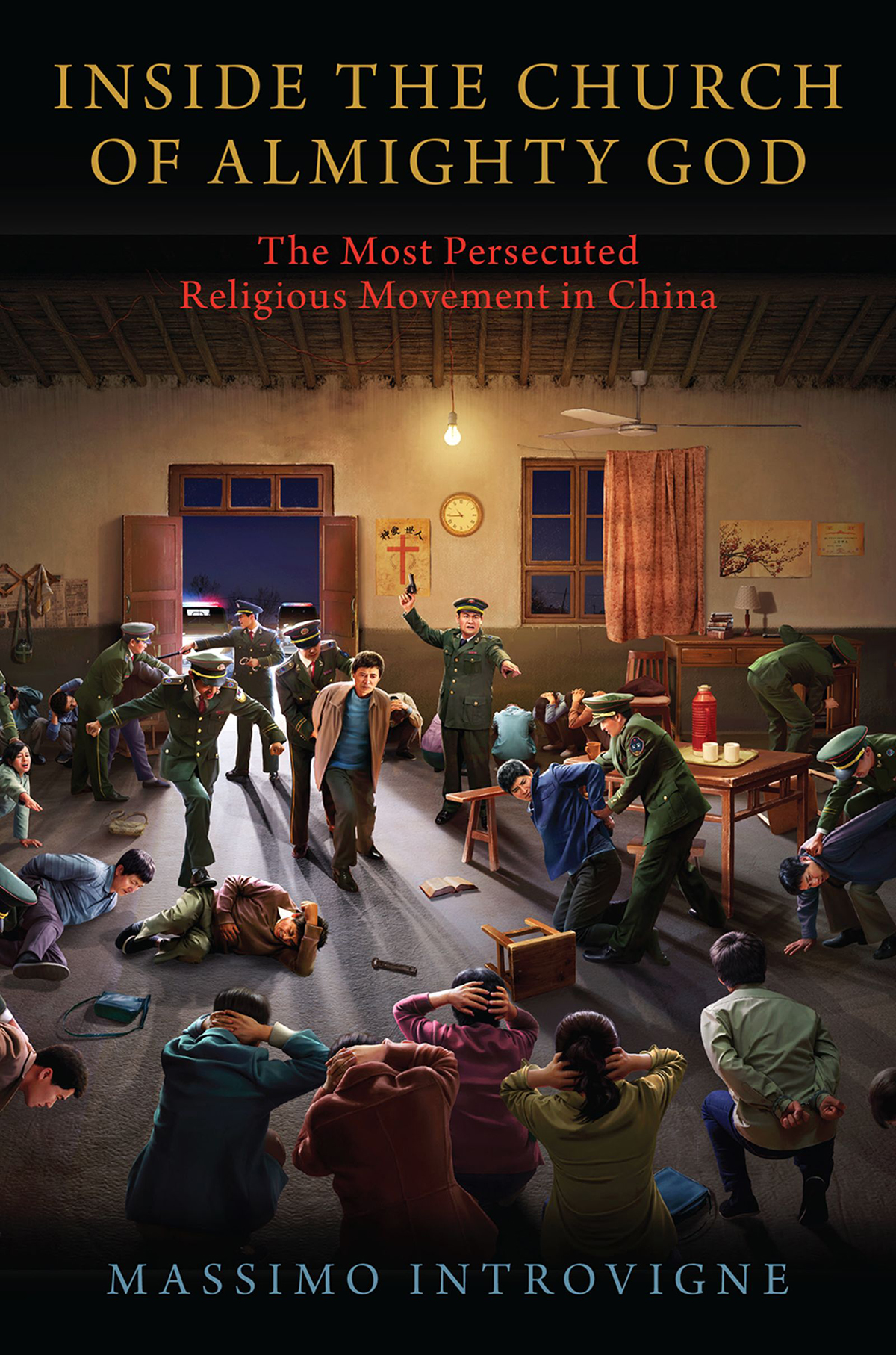

This book starts by relating stories of Chinese believers who were arrested, detained, and in some cases, tortured and killed because of their faith. All the stories concern members of The Church of Almighty God. While the literature on religious persecution in China often disguises the names of the victims in order to avoid retaliation on their relatives, in the stories I relate in the first chapter all names are real.

But membership in The Church of Almighty God is not the only element these refugees have in common. They are all supported by affidavits sworn and submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva for the Universal Periodic Review of China in 2018 (with the single exception of the case of Jiang Guizhi, whose affidavit, although duly sworn, did not reach Geneva on time and could not be filed). Every five years, each member state of the United Nations is expected to submit to the Human Rights Council an assessment of its human rights record. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) may also present reports on the human rights situation in a country. Those Universal Periodic Reviews submissions found to be admissible are published on the Human Rights Councils website. With respect to the Universal Periodic Review of China, six different submissions mentioned the persecution of The Church of Almighty God. One was cosigned by Coordination des associations et des particuliers pour la libert de conscience, an NGO enjoying consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.

It is notoriously difficult to prove torture and extrajudicial killings in totalitarian regimes. However, in the case of the members of The Church of Almighty God, Chinas Universal Periodic Review of 2018 was a turning point. The persecution of church members was mentioned in the Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, summarizing the submissions received about China (evidence is being collected, documenting that the abuses against the devotees of The Church of Almighty God in China are very real. Without being accused of specific crimes, thousands of members of the church have been arrested and sentenced to long terms of detention and forced labor. As I will detail with specific examples, being a member of The Church of Almighty God or simply found in possession of its literature is enough to warrant arrest.

But what is The Church of Almighty God? And why is it persecuted? The Church of Almighty God (CAG), in Chinese Quannengshenjiaohui (), is a Chinese Christian religious movement, founded in 1991, also known as Eastern Lightning. The latter name refers to a passage in Matthew 24:27: For as lightning that comes from the east is visible even in the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. This lightning that comes from the east, according to the church, is Jesus Christ returning as Almighty God, that is, as a person born in China, a country in the East, to inaugurate the third age of humanity.

The persecution of the CAG was started because of its phenomenal growth, which panicked the authorities, and its theology, which teaches that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been consistently resisting God and incarnates the evil red dragon of the Book of Revelation. Is the CAG really a threat to the CCP, or is it just another independent Christian movement in China, misunderstood but inoffensive?

In this book I try to answer basic questions about the CAG. As a starting point, I explain how and why certain groups in China are labeled xie jiao (, heterodox teachings) and persecuted. I then present the history, main beliefs, and practices of the CAG, seeking to explain its rapid and surprising growth. I address the Chinese regimes persecution of and media attacks against the CAG and the main criminal accusations, including homicides and kidnappings, raised against this movement. Although some incidents are open to different interpretations, investigations by independent scholars have so far identified such accusations as part of a massive and spectacular campaign of fake news, created by the Chinese regime in order to justify a persecution that was started, for political and ideological reasons, well before the CAG was accused of any crime.

In its campaign against the CAG, the CCP has been supported by Christian groups that see the CAG as a dangerous, heretical group, even a cult. Its theology is undoubtedly original, although CAG believers claim that their doctrine simply comes from the words of Almighty God, the returning Jesus Christ of the last days, which produced a latter-day sacred scripture. Their point of view should be understood and respected. Most scholars, aware that its theology is certainly different from that of traditional Christian churches, describe the CAG as a Christian new religious movement. The American scholar Holly believes that the concept of Christianity is continuously developing. She argues that even though the CAG has proposed innovations with respect to traditional Christianity, its theology is ultimately rooted in Protestantism and it has maintained Protestant continuities with respect to mainline Christian teachings. She concludes that the CAG should indeed be considered a Christian movement (68).

Like all religious movements, the CAG did not arise in a vacuum. It emerged during the early 1990s revival of Chinese Christianity within a network of house churches whose theology was indebted to both the Reformed and the Brethren traditions. Understanding these roots, and CAG beliefs, is not a purely theological exercise. It is because of both its rapid growth and its theology, which includes criticism of Marxist atheism, that the CAG is perceived as an enemy by the CCP.