Contents

Page List

Landmarks

ALSO BY ROBIN C. WHITTAKER

Hot Thespian Action!: Ten Premiere Plays

from Walterdale Playhouse (editor)

ALSO BY SUZANNE MCKENZIE-MOHR

Women Voicing Resistance: Discursive and

Narrative Explorations

(co-editor with Michelle N. Lafrance)

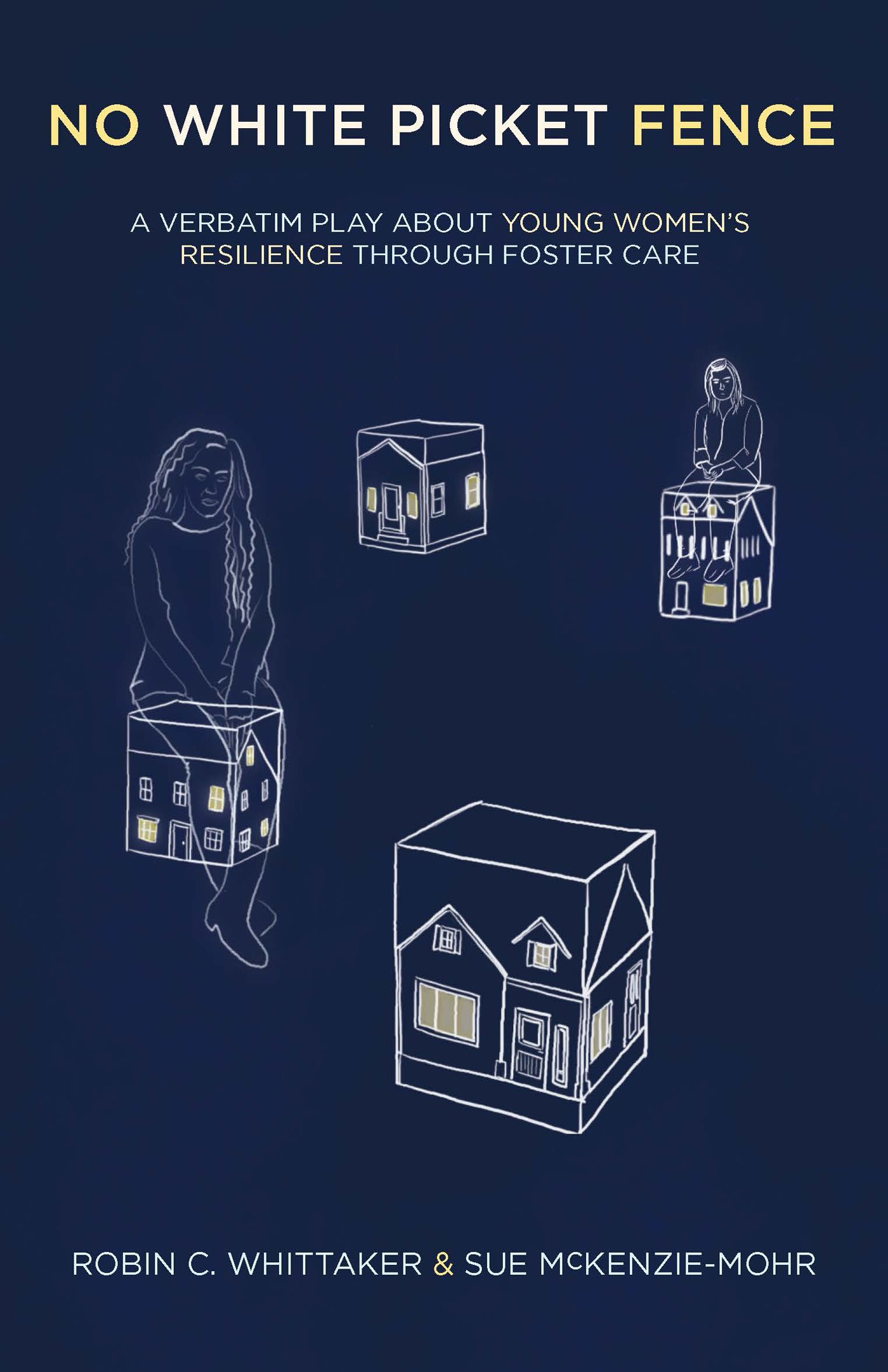

NO WHITE PICKET FENCE

A Verbatim Play About Young Women's

Resilience Through Foster Care

Robin C. Whittaker

and Suzanne McKenzie-Mohr

Talonbooks

2019 Robin C. Whittaker and Suzanne McKenzie-Mohr

Foreword 2019 Kathleen Gallagher

Afterword 2019 Robyn Lippett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from Access Copyright (The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For a copyright licence, visit accesscopyright.ca or call toll-free 1-800-893-5777.

Talonbooks

9259 Shaughnessy Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6P 6R4

talonbooks.com

Talonbooks is located on xwmkwm, Swxw7mesh, and slilwta Lands.

Interior and cover design by andrea bennett

Talonbooks acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Rights to produce No White Picket Fence, in whole or in part, in any medium by any group, professional or amateur, are retained by the author. Interested persons are requested to contact Robin C. Whittaker at Department of English, St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada E3B 2J7; or by email: .

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: No white picket fence : a verbatim play about young womens resilience through foster care / Robin C. Whittaker and Suzanne McKenzie-Mohr with a foreword by Kathleen Gallagher and an afterword by Robyn Lippett.

Names: Whittaker, Robin, 1976 author. | McKenzie-Mohr, Suzanne, author. | Gallagher, Kathleen, 1965 writer of foreword. | Lippett, Robyn, writer of afterword.

Identifiers: Canadiana 20190105755 | ISBN 9781772012415 (Softcover) | ISBN 9781772012996 (ePUB) | ISBN 9781772013009 (Kindle)

Classification: LCC PS8595.H4964 N6 2019 | DDC c812/.54dc23

For those who have had challenging experiences before, during, and following their time as Youth in Care, and yet have persisted in their efforts to live well.

In particular, for the ten young women who trusted us with their rich and complex accounts and collaborated with us in preparing this play. They have our gratitude and deep respect.

This play includes stories featuring emotional and violent experiences.

Audience and reader discretion is advised.

FOREWORD: FASHIONING TRUTH TO THINK OTHERWISE

by Kathleen Gallagher

ATTICUS (male, Native and Nigerian, middle class, straight, believes in God, first language English, other language Ojibway): Um, verbatim is unlike other ones, its more natural, more organic, more personal. And its more different than other plays that are out there, and its just more organic.

SCOTT (male, white, research assistant): Organic. What do you mean by that?

ATTICUS: Like its, I dont know, it hasnt been tweaked, it hasnt been, like, touched, like its untouched, its natural. Its more from the heart than it is from, like, the mind.

Atticus is a young person in my current ethnographic research project, which uses verbatim theatre as a creative and research methodology. In this exchange, he is being invited to reflect on his experience of making a verbatim play with his drama classmates. His answer points both to the presumed techniques of the form (it hasnt been tweaked) and the kind of communication it initiates (Its more from the heart than it is from, like, the mind). For this young theatre-maker, it is a value to keep things in their original form, untouched. He further characterizes verbatim theatre as a communication from the heart, as a feeling project rather than an analytical one.

Playwright Andrew Kushnir defines verbatim theatre modestly:

Documentary or verbatim theatre involves dramatizing text that has been crafted from interview transcripts or the carefully tran scribed footage of real-life encounters and events. It produces a fictional non-fiction experience in the theatre wherein the actual words of often-underrepresented voices (or historically misrepresented voices) take the stage.

A fictional non-fiction experience is a novel way to think about live theatre. Verbatim is indeed a fictional experience of a real or non-fiction world. Yet my research tells me, interestingly, that at its point of reception, audience members often feel that this fiction is more real than reality. Mya Ibrahim (female, Somali, heterosexual, middle class, Muslim, first language English, other languages Somali and Arabic), a classmate of Atticuss, says assuredly: Its more real, but its not real.

How can something be more real but not real? What work is verbatim theatre doing when its created world evokes a communication more real than real life? David Hare, one of verbatims fiercest proponents in its early days, believed it was communicating real life to us better than those appointed to do so, journalists and news reporters. He believed that journalism produced life with the mystery taken out whereas art created life with the mystery restored. He argued further that there was a hunger for the fullness and complexity of reality that journalists themselves were failing to deliver on. That very idea, though, also made verbatim theatre suspect in its early days; had it sacrificed aesthetic expression and found itself caged by reality? Hare disagreed:

Particular objection is made to the use of other peoples dialogue. No sooner had a genre called verbatim drama been identified than sceptics appeared arguing that it was somehow unacceptable to copy dialogue down, rather than to make it up. People who did this, it was said, are called journalists, not artists. But anyone who gives verbatim theatre a moments thought or rather, a dogs chance will conclude that the matter is not as simple as it first looks.

Today, one might find verbatim theatre tethered to various forms of research across a range of disciplines, where researchers aspire for their work to reach a wider audience or to communicate in voices beyond scholarly ones. No White Picket Fence speaks to such a collaboration between its creators.

Whether verbatim theatre is built from scholarly research, a playwrights own observations and interactions, popular culture, or the news cycle, complex ethical, social, and artistic questions converge at the nucleus of its practice. Consequently, verbatim plays always invite critical discussion about its social and aesthetic value, as well as its dangers. As with research, the relationships at the core of verbatim theatre practice are what matter most: Have the subjects been served by the play? Does the play amplify their voices and questions? Does the aesthetic representation provide an ethical and compelling frame for their worlds? Andrew Kushnir understands his verbatim work as an act of transference rather than translation. When audiences have suggested that his plays have given voice to their subjects, he balks: