Life is full of trialsyet sometimes we may suddenly perceive an eternal light in the midst of the worst tribulations. There is much in life that does not make any sense, so we need witnesses whose life says: and yet! and who keep on smiling through their tears. This book is such a smile, compelling in its authenticity.

Benot Standaert

Benedictine monk of Saint Andrews Abbey in Bruges, Belgium

Author of Sharing Sacred Space: Interreligious Dialogue as Spiritual Encounter

Learn to be still and learn to do nothing and learn to wait.

The secret of those who became giants always lay in this: they were prepared for the long haul.

Thus wrote poet Henriette Roland Holst.

It is what Bieke Vandekerckhove wanted to learnliving with an incurable disease, she had to. Listening, meditating, persevering in the silence, she became one of the giants, and she wrote a book that consoles.

Huub Oosterhuis

Dutch theologian, poet, author, liturgist, and ecumenist

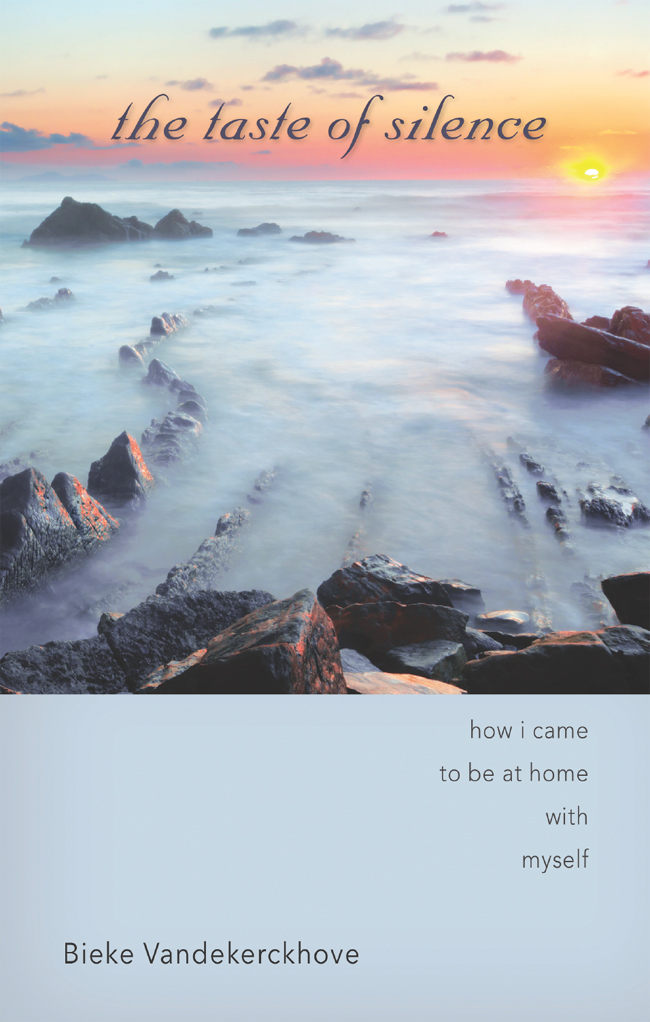

De smaak van stilte 2010 by Bieke Vandekerckhove

Originally published by Uitgeverij Ten Have, Utrecht

Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover photo: Dreamstime.

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

2015 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint Johns Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vandekerckhove, Bieke.

[Smaak van stilte. English]

The taste of silence : how I came to be at home with myself / Bieke Vandekerckhove ; translated from the Dutch by Rudolf V. Van Puymbroeck.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8146-4773-8 ISBN 978-0-8146-4799-8 (ebook)

1. Spirituality. 2. Spiritual life. I. Title.

BL624.V34513 2015

204'.4dc23

2015003707

For Gaby, who taught me to live the great silence,

and for Bart, my love and companion on the journey.

do not close the windows

soon it will enter

the greatest silence.

J. C. van Schagen

contents

Ton Lathouwers

foreword to the Dutch edition

The first image that comes to me, now that I am writing this foreword to Bieke Vandekerckhoves book, is that of the wall. This image has stayed with me ever since I first encountered it in Dostoevsky, some sixty years ago. Ten years later, when I was studying Slavic languages, it showed up again in my favorite Russian-Jewish author, Lev Shestov. In Shestovs work I encountered the phrase that every authentic search ends in a lonely path, and that all lonely paths inevitably end at a wall. Another ten years later I came across this wall again in classic Zen literature, the best-known collection of which is aptly called Wall without Gates.

This image of the wall runs like a red thread through the taste of silence, even though Bieke does not say so explicitly. Perhaps I can best clarify its meaning by giving two citations. The first is from Dostoevskys novel Notes from the Underground, the second is borrowed from the final chapter of Wall without Gates:

One can understand everything, have insight into everything, every impossibility and every stone wall, and yet not resign oneself to a single one of these impossibilities and stone walls.

Dont be surprised that walls without gates prove to be so difficult and that they trigger intense anger in Zen monks!

In one of the chapters of the book, Bieke expresses in a particularly moving way what is referred to in these quotations. Its the chapter in which she talks frankly about her own experience in hitting the wall, in coming to a dead end that appears impossible to accept, but at the same time, realizing that this dead end must never be allowed to have the last word. Bieke uses an impressive quotation from French author Sylvie Germain about the insufficiency and the impotence of current religious language when faced with this dead end. The biblical figure of Job occupies a central role for her. Job perfectly reflects what is meant about the wall in the two quotations above: anger, rebellion, a holy nonacceptance and nonacquiescence, and, especially, a refusal of every attempt at explanation and justification of what is unacceptable.

And precisely there, in the apparently senseless screaming and raging of Job, may lie an unexpected opening. Precisely here one can fall silentTo Fall Silent is also the title of a movie about Biekethe unconditional option for silence as the only way that remains. For me, Biekes quotation from Sylvie Germain is one of the most impressive expressions of witness in her book. It translates her own yelling, her own revolt against the wall, and finally her own entering into the silence, the silence of Zen meditation with which she has become familiar now for so many years.

This is the other image of the wall, the wall that can never be conquered with words and violence. This is the other image of the wall that stands at the beginning of the Zen tradition. It is said of the legendary founder of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, that he sat in meditation in front of a wall for a full nine years before finally breaking his silence. This is how he expressed his own waiting and vigil in silence and mindfulness, his own not-knowing and his own, based on nothing, primal confidence that the wall does not constitute the last word, that no wall constitutes the last word.

At one time Bieke told me that it was exactly the confrontation with the wall that taught her to look for what she called the deepest reality. What I found particularly moving was the fact that she translated the abstract-sounding deepest reality in a manner that rendered it concrete and immediate. Ill never forget her reaction to a Russian story I told her about a dying young soldier in the Second World War who, just before he passed away, only had interest in a blue dragonfly that flew above the water close to him. She recognized immediately that the seemingly incomprehensible captivation of this dying boy by something so simple was a profound revelation at the edge of eternity. Yes, so common and at the same time so uncommon is the deepest reality, she wrote me.

There is also a whole other way in which Bieke appears to be extremely close to the deepest reality. Time and again she forgets her own suffering when she sees the difficulties of others. By a fortuitous set of circumstances in the past few weeks I witnessed this myself. Acting in this way, she expresses, in a manner that serves as an example to me and many others, what is most essential in Mahayana Buddhism, of which the Zen tradition is a part. The deepest reality is not, as is so often supposed, an engagement with our own well-being but, rather, the fact that our own deliverancewhatever that may meanis unconditionally connected with the deliverance of the other. This is summarized in a short and powerful manner in the so-called First vow of the Bodhisattva, which is recited daily in all Zen temples: No matter how numerous the living beings may be, I commit to liberate them all.