Guide

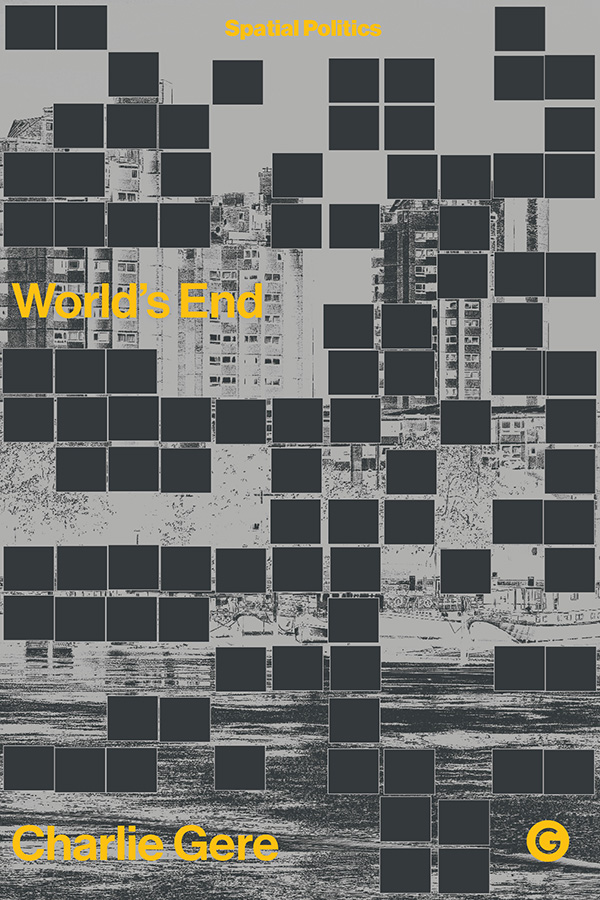

Worlds End

Worlds End

Charlie Gere

Copyright 2022 Goldsmiths Press

First published in 2022 by Goldsmiths Press

Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross

London SE14 6NW

Printed and bound by Versa Press, USA

Distribution by the MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Copyright 2022 Charlie Gere

The right of Charlie Gere to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and review and certain non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-913380-00-7 (hbk)

ISBN 978-1-912685-97-4 (ebk)

www.gold.ac.uk/goldsmiths-press

d_r0

There are far too many people to thank properly, but the following must be mentioned; my father and mother, obviously, for making me, in Chelsea, and therefore making this book possible and also for choosing to live in such an aptly named district; my sister, Cathy, of course; Jenn Ashworth for her comments, as well as our ongoing conversations and her steadfast and generous encouragement of my writing; Matt Fuller and Arthur Bradley for their insightful comments; Ruth McLennan for graciously allowing me to quote her part of a private Facebook conversation; Sarah Cormack, for her comments, and for getting in touch out of the blue, and making me think about the more distant past; the editorial team at Goldsmiths Press, and their anonymous reviewers; and to all those friends, some of whom I have known since the 1970s or even 1960s, with and beside whom I have lived this life, especially my family Lucinda, Matilda and, above all, Stella, who says that I never talk about my past, and to whom I dedicate this book.

Contents

When making my will a few years ago I was asked to choose what should happen to my body after death. Without hesitation, I said I would like to be cremated and have my ashes scattered in London, in the river at the Worlds End at the wrong end of the Kings Road, in Chelsea. In returning at, or after my end, at least in my imagination, to where I started, seemed right and seemed to exemplify the idea that life is a detour on the way to a return to where one starts. It was right that my world should end, where it started, at the Worlds End.

I rehearsed this final journey when Covid-19 struck in 2020 and we decided that it would be best if I went down to London to help my mother during the lockdown. This meant returning to my childhood home. The London I returned to was uncannily like the city of my youth, in that it felt empty, in marked contrast to its recent state of crowdedness. Before the virus, London had become almost unbearably full, choked with traffic and crowds. A bus journey that had taken twenty minutes in the 1960s or 1970s, now lasted a minimum of an hour and often longer. Now the streets were almost entirely devoid of traffic.

I recently came across some extraordinary images taken by Jon Savage, better known as a writer on Punk and related forms of music. They show North Kensington in the mid-1970s, an unrecognisable place of dereliction and emptiness.in 1939, a figure only reached again in 2015. In the thirty years after 1939 the population dropped to 6.6 million, meaning that it was at its emptiest when I was a child and adolescent.

During the lockdown people mainly walked, alone or in pairs, with occasional family groups. Planes no longer flew over my mothers house, on the flightpath to and from Heathrow in the early morning. The city was strangely, eerily, silent. To prevent the spread of contagion, supermarkets only allowed a limited number of shoppers in at a time. People patiently queued, spacing themselves at the recommended two metres or six feet. The strangeness of the experience was compounded by the sight of police cars patrolling slowly around the streets, as if about to enforce the quarantine. I noticed that the police were armed with what appeared to be submachine guns, which added to the sense of foreboding. Under all this there was the continual sense of anxiety, the fear that some contact with another human, or even with a tainted surface, might cause infection, maybe mild or even asymptomatic, but possibly extremely painful or even deadly.

My return to London was motivated not just by the need to help my mother but for other, less noble, reasons. I was intensely curious to experience the city in which I had been born, and spent most of my life, under these unprecedented conditions. I wanted to witness this epochal event, which was bound to change the world entirely, close up, in one of the centres of the outbreak. To a great extent this was just a kind of car-crash voyeurism. I find catastrophes and disasters frightening but also exhilarating and fascinating. There was also a kind of atavistic pull of home, to return to the Worlds End, at what seemed at times to be the end of the world. It seemed to me that the current sense of dread caused by the virus was something I had felt all my life.

At the same time, I felt a curious joy all the time, which seemed entirely inappropriate in the circumstances. This was down to some extent to the sense of being on a kind of holiday, from the day-to-day banalities and repetitions of family and work, and also due to the extraordinary weather, with the beautiful spring greatly enhanced by the lack of traffic, cars and also airplanes on the Heathrow flightpath, and the general emptiness of the streets. I walked, with my mother, and with friends, all over the parts of London reachable by foot, seeing the houses and sights clearer than ever before. But it was something else besides these pleasures. Towards the end of my stay, after nine weeks, I had an at first unaccountable desire to re-read Thomas Manns The Magic Mountain. It seemed to me that London during Covid was a bit like the sanatorium in Manns book, in which the mundane time of the valley below was suspended. However, this did not mean no time but many times co-existing in the emptied city. Something of this is caught by one of the characters in Michael Moorcocks London masterpiece Mother London.

We move through Time at different rates, it seems, only disturbed when anothers chronological sensibility conflicts with our own. Choices as subtle and complicated as this are only available in a city like London; they are not found in smaller towns where the units, being less varied, are consequently less flexible. Past and future both comprise Londons present and this is one of the citys chief attractions. Theories of Time are mostly simplistic attempting to give it a circular or linear form, but I believe Time to be like a faceted jewel with an infinity of planes and layers impossible either to map or to contain; this image is my own antidote for Death.