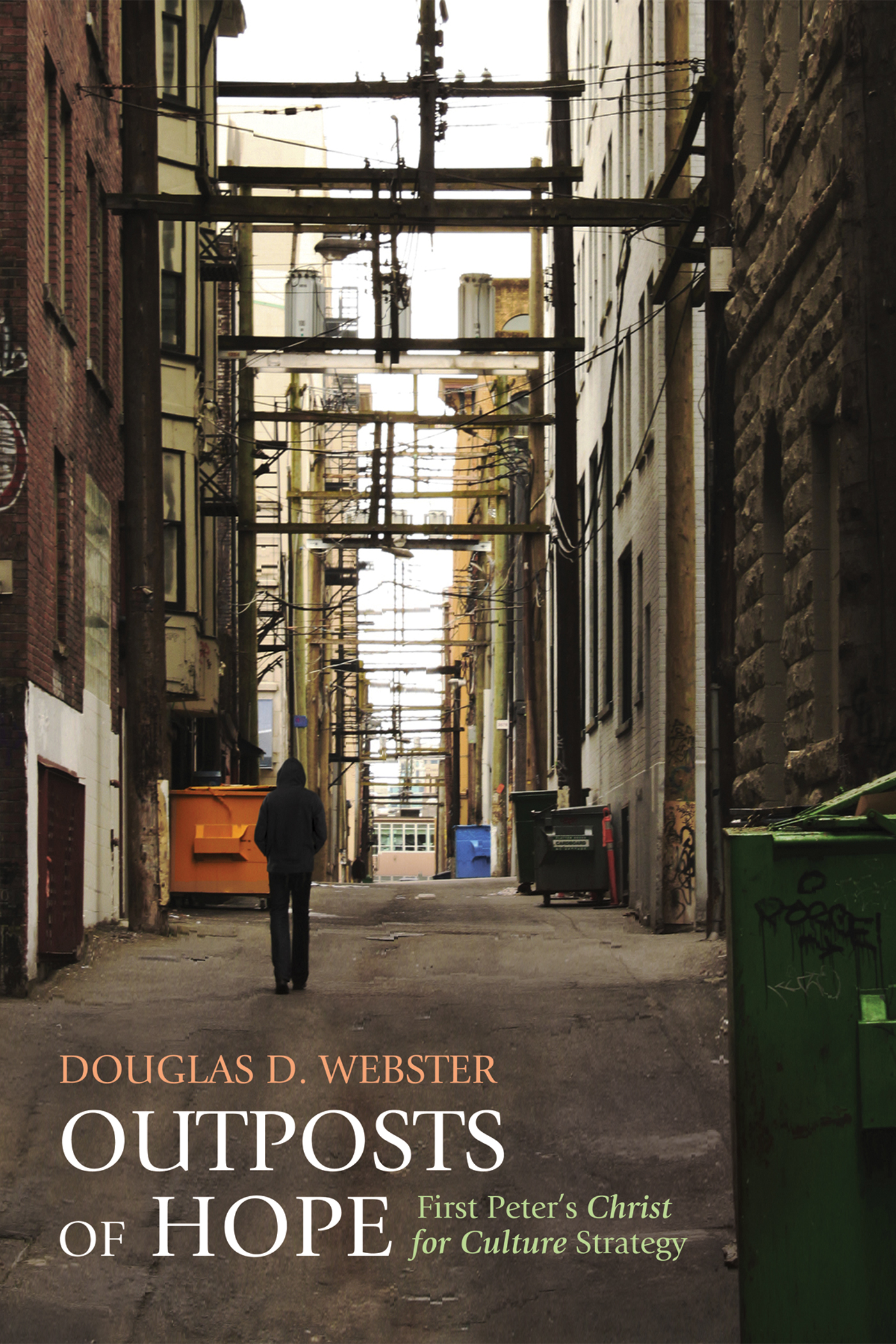

Introduction

F irst Peter is important because it develops the believers foreign status and strangerhood in fresh ways that Christs followers have not typically embraced. It critiques post-biblical Christianity in the West and inspires no-fear discipleship in the global church. Peters focus is not on the badness of culture but on the goodness of the Christian even when confronted by social hostility.

A Parable

Toward the end of my senior year at Wheaton College, three friends and I took a two-day canoe trip down the Vermillion River in Illinois. None of us had ever been on the river before and we were using a Girl Scout guidebook to navigate. We thought we had lined up the guidebook with where we started on the river. The first day out the book warned of dangerous rapids, but when we came to rapids they were gentle, nothing to worry about. Then the book warned of a waterfall that we might need to portage around, but it too proved uneventful. The guidebook indicated that the river was especially dangerous around an old factory, but we passed by what we thought was the old factory without incident. By now we were laughing at the Girl Scouts and their wimpy guidebook. We were ridiculing its warnings and mocking its notes of caution. We ended our first day around a campfire thumping our male chests and trashing the Girl Scout guidebook.

The next day we came to a set of rapids that was dangerous, followed by a waterfall steep enough to capsize our canoes, followed by an old factory, where the current and the rocks were so treacherous we had to portage. By now it was clear that we had lined up the guidebook with the wrong section of the river. The Girl Scouts were right after all. What they said was dangerous truly was dangerous. Where the river got serious, the guidebook got serious. We were getting much better advice than we thought we were. Our failure to line up the guidebook with the river was our big mistake.

Most Western believers, myself included, read Peter the way we read the Girl Scout guidebook. It doesnt line up with our experience so we question its relevance. But sooner or later, if we are serious about following Jesus Christ, we will find ourselves in Peter.

Lining up First Peter

The family of believers throughout the world is undergoing the same kind of sufferings. Peter :

Peters thesis is this: the followers of Jesus Christ are strangers in their own homeland. To be born again into a living hope is to become a foreigner in the land of ones birth. Without moving from one country to another, and without crossing any political or regional boundaries, Christians became resident aliens. The impact of the gospel is theological and sociological. Because of Christ, believers re-enter their home culture as immigrants, foreigners, who for all practical purposes are now strangers without status in their home culture. Christs followers become exiles without being deported, migrants without migrating, and foreigners without traveling to a foreign country. Believers are resident aliens by virtue of their newfound faith in Christ. First Peter is about the social impact of life in Christ and the inevitable clash with culture than ensues because of the sheer contrariness of the good news of Jesus Christ.

Suffering and submission are two of Peters main themestwo unpopular subjects for most believers, but truly essential for Peters Christ for culture strategy. He wrote to Christians experiencing cultural pressures and social hostilities foreign to many of us today, not because we live in the Christian West or in a free and democratic society but because we have abdicated the meaning of biblical discipleship. We suffer little because we stand for less than the first recipients of Peters letter. The apostles spiritual direction does not apply to us because we have not applied ourselves to New Testament Christianity. As David Bentley Hart notes, we have obscured the very real and irreducible element of sheer contrariness involved in setting apart Christ as Lord. Whether it is read in rural Asia Minor or the American Midwest, the gospel is essentially subversive of the accustomed orders of human power, preeminence, law, social prudence, religion, and government.

The Danish Christian thinker Sren Kierkegaard believed that there was nothing in the popular Christianity of his day that warranted persecution. Christians were assimilated into the culture so completely that there was no real difference between a Christian and a non-Christian. Everyone was a Christian, because no one was a Christian. The world does not persecute the world when it discovers itself in Christianity. Christians cannot be at home in the world and at the same be a stranger and a pilgrim in the world.

Kierkegaard lamented that Christianity marches to a different melody, to the tune of Merrily we roll along, roll along, roll along Christianity is enjoyment of life, tranquilized, as neither the Jew nor the pagan was, by the assurance that the thing about eternity is settled, settled precisely in order that we might find pleasure in enjoying this life, as well as any pagan or Jew.

Post-biblical Christianity is altogether different from the Christianity described in the New Testament. Popular Christianity reflects the spirit of the times, not the Spirit of Christ. It is compatible with and conformed to the prevailing culture, whether it be imperial Rome or capitalistic democracy. This Christless Christianity views the New Testament as an historical curiosity, a cultural artifact, to be read out of religious habit or studied as an intellectual exercise.

Kierkegaard proposed a way to end the hypocrisy.

Let us collect all the New Testaments we have, let us bring them to an open square or up to the summit of a mountain, and while we all kneel let one person speak to God thus: Take this book back again; we humans, such as we are, are not fit to go in for this sort of thing, it only makes us unhappy.... This would be an honest and human way of talkingrather different from the disgusting hypocritical priestly fudge about life having no value for us without this priceless blessing which is Christianity.

No one takes the Bible seriously anymore because the world is compatible with popular Christianity. Love is god; not God is love. Past perversions are celebrated as freedoms and tolerance trumps truth. Self-expression is the new sacred and a passion for Christ is comfortably compatible with all other passions. No one discerns the difference between obsession and devotion, fandom and faithfulness, consultants and ministers. Everyone does what is right in their own eyes.

First Peters major themes, suffering and submission, may be relevant for believers living in North Korea but they may seem remote to believers living in North Dakota. We are no longer socially marginalized or ostracized because our Christianity is in bland conformity to the world. We no longer need to encourage believers to endure persecution because the world finds nothing in our lives to persecute. This makes Peter virtually irrelevant to the bulk of Western readers, because too much of it is centered on aspects of Christian existence that are far from most Western Christian experiences: social marginalization and suffering. Instead of questioning popular Christianitys cultural conformity, the assumption is made that our world is much nicer and better than first-century Asia Minor.