Praise for The Monks of Tibhirine

By Mr. Kisers own evidence, Muslims in general are not at war with the West in general, or Christianity in particular. What he does quite well is tell the story, at once sad and inspiring, of very good men who took their vocation seriously and died for it.

The Wall Street Journal

After two years of research and interviews, Kiser chronicles the vision that inspired the monks and the idealism and commitment that kept them in Algeria, despite the increasing violence and approaching danger.

Library Journal

Kisers book is an attempt to find an answer to what are perhaps the central questions of our humanity: How to live with our neighbor? What is the meaning of community? The lives of these monks gives thought-provoking answers.

East Hampton Star

Mr. Kisers work is beautifully researched, and very, very difficult to put down. It serves a dual purpose, each one worthy of a book on its own. The first is to provide a contrast between the terrorist factions who abuse Islam as a tool, and the people of Tibhirine, who practice Islam as brotherhood.

Islamic Horizons Magazine

This book is a timely view of an Islam that is not just about hatred and brutality. The book is spiritually uplifting and extremely moving.

Roanoke Times

Well written and extremely well researcheda valuable addition to the literature about modern Algeria. I plan to recommend it to all officers going on assignment there.

Peter Bechtold, U.S. Foreign Service Institute

An intellectual and emotional journey through the transcendent themes of faith, hate, war, and reconciliation. The Monks of Tibhirine is not only a penetrating account of recent historical events, but of ideas and ideologies driving them.

Susan Eisenhower, director, Eisenhower Institute

The Monks of Tibhirine is a work of great sensitivity. His insightful prose weaves complex themes from Algerias history into a single life-affirming whole. It transforms tragedy into hope for the future of Christian-Muslim relationsmost inspiring!

Abdul Aziz Said, director,

Center for Global Peace, American University

A remarkable book about love, respect, and forgiveness. It should be read by people of all faiths who seek to live in peace. John Kiser makes the monks and the world they inhabit come alive.

Elizabeth Swenson, executive director,

The Friends of St Benedict

Kiser reconstructs patiently and impartially the sad story of an Algeria, in which spirituality and violence, peace and war, great hopes, and great contradictions are skillfully interwoven. The book is a testimony to the living pain of a country in search of an identity.

Marco Impagliazzo, vice president,

Sant Egidio, Rome

John Kiser has done a wonderful job in writing about this gem of a story. His telling of it is very convincingthe lives of Christian de Cherge and his brothers were a gift of hope.

Andrea Bartoli, director, Institute of Peace and

Reconciliation, Columbia University

To the monks of Tibhirine, and to those who loved them

Algeria is land and sun. Algeria is a mother, cruel and yet adored, suffering and passionate, hard and nourishing. More than in our temperate zones, she is proof of the mix of good and evil, the inseparable dialectic of love and hate, the fusion of opposites that constitute mankind.

A LBERT C AMUS

Contents

Acknowledgments

Like Trappist monks, writers do their real work alone, but their efforts are sustained and bear fruit only with the help and support of others. Without the trust and good faith shown by the families and friends of the monks, this book could never have been written. To them, I am especially grateful for letting a stranger share in their memories and sadness.

I would like to thank Bruno Chenu, the former editor of La Croix , who, in the spring of 1997, connected me to the right people as I was starting my research. One of those was Marie-Christine Ray, who was extraordinarily generous with her time and sources. She was working on a biography of Christian de Cherg, and her own timely research was of great benefit to me. I am deeply indebted to Bishop Henri Teissier and his colleague Gilles Nicolas for the support they provided during my visit to Algeria in 1999. Others, too numerous to mention, included journalists, friends of the monks within and outside of the Order, diplomats, and scholars.

For moral support in the early stages, I owe much to Ned Chase, Susan Eisenhower, and Carol Edwards, whose interest and preliminary editorial help led me to Michael Denneny, my editor at St. Martins Press. Michaels wise guidance was invaluable in weaving together the different strands of the story.

I am also indebted to the many friends and acquaintances who took the time to read and comment on the manuscript, often with great care. One of those was Dean Fischer, former Time magazine bureau chief for the Middle East, who was struggling with cancer at the time. Mireille Luc-Keith, my good friend and research assistant, read it more often than anyone, possibly even more than I did. I am deeply appreciative of her commitment to this undertaking, enthusiasm, and meticulous attention to the seemingly endless details.

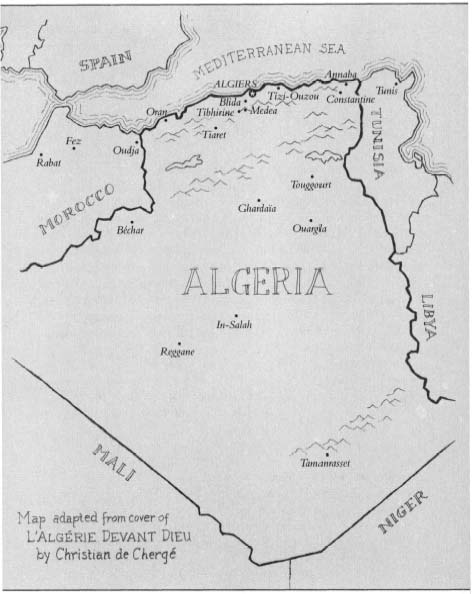

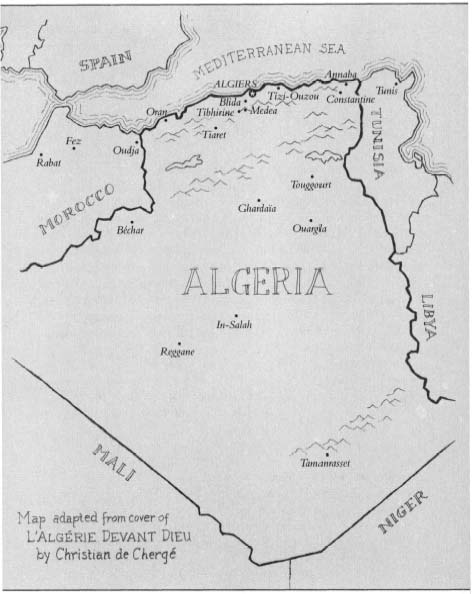

M AP OF A LGERIA

Authors Note

This is a true story. Yet truth, as we know, is a many-faceted thing. Of one thing I am sure: This is not the whole truth.

Quoted passages represent excerpts from published materials, monastic communications, or interviews. I have accounted for my principal sources in the chapter commentaries at the end of the book, rather than with detailed footnotes. Italics are generally reserved for citations from the Koran, the Bible or the Benedictine Rule, and, in some cases, when I have quoted extensively from articles or documents. Koranic citations are from the Penguin Classics translation by N. J. Dawood, first published in 1956. Biblical quotations are from the New King James Version. Foreign words are defined in the glossary, as are basic Islamic religious terms and concepts.

Introduction

I first met Robert de Cherg in the lobby of the Grand Htel Concorde in Lyons. I had written him of my interest in doing a book about the monks of Tibhirine, whose prior, Christian de Cherg, was his younger brother. He had immediately replied to me in Paris, where I was staying at the time, and invited me to come down to talk. I was somewhat nervous about meeting this retired general from the nuclear artillery branch of the French army who was the designated doorkeeper for screening journalists, writers, and others seeking access to the monks families.

The story of the kidnapping and murder of seven French Trappist monks in Algeria had been all over the European press during the summer of 1996. Their monastery of Notre-Dame de lAtlas in Tibhirine was known as a place of friendship between Muslims and Christians. For four years, both the monastery and the village nearby had been spared the violence that raged in the mountains around them. The monks eventually became victims in a struggle among Muslims for a more just society, a struggle that had gone horribly wrong and had cost from 60,000 to 100,000 Algerian lives by 1996. Yet the monks were not martyrs to their faith. They did not die because they were Christians. They died because they wouldnt leave their Muslim friends, who depended on them and who lived in equal danger.