More praise forRocks of Ages

Meticulous and evenhanded, Gould explores in turn the history and the psychology of conflict with respectful and compassionate portraits of the players, heroes, and villains. Loving them for their greatness as well as for their human frailties, Gould brings his interlocutors to life with humor and compassion.

Los Angeles Times

This is an ambitious synthesis, but it neither intimidates nor does it seem too far-fetched. Gould appeals to common sense. This small book is heftier than the volumes of inaccessible, jargon-wrapped material produced every year by some academic historians and philosophers. Rocks of Ages should be read not only in all our colleges, it should be read in our temples and mosques, in our churches and synagogues.

Nature

An intriguing volume which should tickle the intellect of the strictly scientific, the strictly devout, and those with membership in both clubs.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

[Goulds] got a chatty, easily read writing style that he wraps around some amazingly sophisticated concepts in biology.

Columbus Ledger-Enquirer (GA)

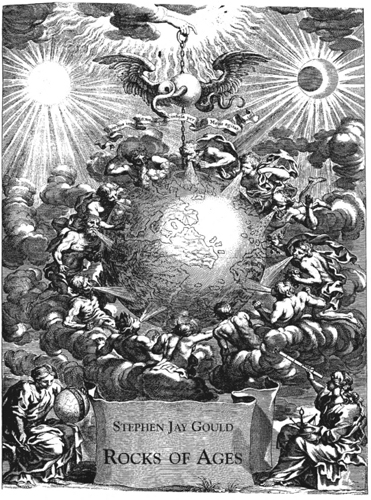

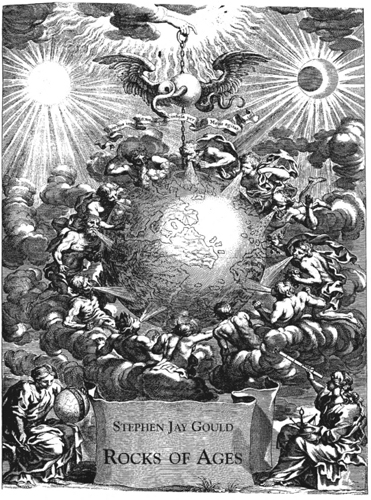

The frontispiece shows the title-page illustration (modified only by a different title and author!) of the greatest geological treatise ever written by a scientist who also held holy ordersthe Mundus subterraneus (Underground World) by the great Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, published in 1664. I regard the figure as a beautiful illustration of science and religion working together in their different ways. God holds the earth in space, but twelve winds in human form control both motion and climate, while the banner cites a famous line from Virgils Aeneid, ending mens agitat molem, usually slightly mistranslated as mind moves mountains (moles, accusative molem, refers to any massive structure).

A Ballantine Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Copyright 1999 by Stephen Jay Gould

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Henry Holt and Company, Inc., and Jonathan Cape Ltd.: Design from The Poetry Robert Frost edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1936 by Robert Frost. Copyright 1964 by Lesley Frost Ballantine. Copyright 1969 by Henry Holt & Company. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company, Inc. and Jonathan Cape Ltd., on behalf of the Estate of Robert Frost.

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., and Random House UK Ltd.: Excerpt form Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History by Stephen Jay Gould. Copyright 1991 by Stephen Jay Gould. Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., and Hutchinson, Random House UK Ltd.

www.ballantinebooks.com

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001119181

eISBN: 978-0-307-80141-8

v3.1

For Jesse and Ethan,

who will have to hold on beyond their fathers watch, and who will surely improve a world with a future so honestly described by John Playfair, a great scientist and writer, who closed his Outlines of Natural Philosophy (1814) by stating (in the old subjunctive mood, where his were equals our would be):

It were unwise to be sanguine,

and unphilosophical to despair.

Contents

Preamble

I WRITE THIS LITTLE BOOK to present a blessedly simple and entirely conventional resolution to an issue so laden with emotion and the burden of history that a clear path usually becomes overgrown by a tangle of contention and confusion. I speak of the supposed conflict between science and religion, a debate that exists only in peoples minds and social practices, not in the logic or proper utility of these entirely different, and equally vital, subjects. I present nothing original in stating the basic thesis (while perhaps claiming some inventiveness in choice of illustrations); for my argument follows a strong consensus accepted for decades by leading scientific and religious thinkers alike.

Our preferences for synthesis and unification often prevent us from recognizing that many crucial problems in our complex lives find better resolution under the opposite strategy of principled and respectful separation. People of goodwill wish to see science and religion at peace, working together to enrich our practical and ethical lives. From this worthy premise, people often draw the wrong inference that joint action implies common methodology and subject matterin other words, that some grand intellectual structure will bring science and religion into unity, either by infusing nature with a knowable factuality of godliness, or by tooling up the logic of religion to an invincibility that will finally make atheism impossible. But just as human bodies require both food and sleep for sustenance, the proper care of any whole must call upon disparate contributions from independent parts. We must live the fullness of a complete life in many mansions of a neighborhood that would delight any modern advocate of diversity.

I do not see how science and religion could be unified, or even synthesized, under any common scheme of explanation or analysis; but I also do not understand why the two enterprises should experience any conflict. Science tries to document the factual character of the natural world, and to develop theories that coordinate and explain these facts. Religion, on the other hand, operates in the equally important, but utterly different, realm of human purposes, meanings, and valuessubjects that the factual domain of science might illuminate, but can never resolve. Similarly, while scientists must operate with ethical principles, some specific to their practice, the validity of these principles can never be inferred from the factual discoveries of science.

I propose that we encapsulate this central principle of respectful noninterferenceaccompanied by intense dialogue between the two distinct subjects, each covering a central facet of human existenceby enunciating the Principle of NOMA, or Non-Overlapping Magistern. I trust that my Catholic colleagues will not begrudge this appropriation of a common term from their discoursefor a magisterium (from the Latin magister, or teacher) represents a domain of authority in teaching.

Magisterium is, admittedly, a four-bit word, but I find the term so beautifully appropriate for the central concept of this book that I venture to impose this novelty upon the vocabulary of many readers. This request for your indulgence and effort also includes a proviso: Please do not mistake this word for several near homonyms of very different meaning