Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte

Edited by

Karl Holl

Hans Lietzmann

Christian Albrecht

Christoph Markschies

Christopher Ocker

Volume

ISBN 9783110790856

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110790900

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110790979

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

In memory of Henryk Wjtowicz

(19282012)

Acknowledgements

This book would not have assumed its present shape had it not been for the help of Pawe Janiszewski, whom I would like to thank for his unflagging support at various stages of my work on the text. I would also like to thank Jan Kozowski, who unfailingly provided me with encouragement to continue my research; our innumerable discussions have especially contributed to bringing the object of this study into sharp focus. I also wish to extend my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers appointed by the Foundation for Polish Science for their insightful criticism. I would also like to thank my wife, Julia Doroszewska, for her daily support, without which no creative work is possible.

Finally, I would like to thank the Hardt Foundation in Vandoeuvres, Switzerland (www.fondationhardt.ch), for the bursary and most pleasurable hospitality that helped me work on this book.

Foreword

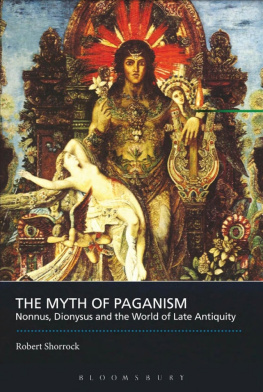

Nonnus of Panopolis, a Greek poet from late antique Egypt who probably lived and worked in the cosmopolitan city of Alexandria in the fifth century AD, is a mysterious figure. Considering the lack of biographical details, scholars have focused their research on Nonnus poetic output, which is a much more gratifying field of study than his biography (which remains difficult to reconstruct). The poets legacy is composed of two works only, but both may prove very interesting to contemporary readers for a number of reasons. The first poem, the Dionysiaca, is the longest of all ancient epics to have survived to this day. As its title makes evident, Nonnus dedicated it to Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, mysteries and ritual ecstasy. Written in forty-eight books and only slightly shorter than the Iliad and the Odyssey put together, the Dionysiaca forms a colourful mosaic of styles, literary references and, often considerably modified, mythological motifs. It is worth mentioning that, as a closer reading reveals, the numerous scenes of the poem refer directly to models derived from Christian literature. In this way, what at first glance might seem to be a companion to the classical Dionysiac mythology proves to be a much more complex work, one that escapes easy categorisation.

The other poem, the Paraphrase of the Gospel of Saint John, is an epic rendering of the deeds of Jesus Christ described in the Fourth Gospel. The simple, meditative language of John gives way to heroic hexameter rhythm and is endowed with Homeric aplomb, while the message of the Gospel, although unchanged, receives an additional dimension. This is especially noticeable in Nonnus use of poetic imagery, often informed by Greek mythology, ambiguous terminology and the interpretative clues embedded in the poem that result from a deep understanding of the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers.

At first glance, the stark difference in subject matter may seem to set Nonnus poems apart from each other to the point of contradiction. This, together with the lack of biographical information, has given rise to numerous, often very peculiar conjectures regarding the Panopolitan poet. His lively and intriguingly puzzling interest in Jesus and Dionysus has provoked scholars to see Nonnus poetry in the light of the purported twists and turns of his life: some have suggested that he had been a recalcitrant pagan who ultimately converted to Christianity, whereas others, contrarily, presumed that he was first a Christian but later apostatised, and still others held that he had regarded pagan and Christian beliefs as a mutually intertwined, syncretic whole. Views on the literary quality of his epic poems were also exceedingly disparate: they were decried as decadent, bloated, chaotic and soporific, but also, especially in recent decades, recognised for their seductively innovative and original characteristics that draw the reader into a whirl of highly erudite allusions.

The fragmentary and conjectural image that emerges from research on Nonnus biography gave rise to a number of fictional, pseudo-biographical writings. Among them, we find both deftly fabricated forgeries and genuine literary works that emerged in response to questions that vexed those who were especially fond of Nonnus poetry. In the nineteenth century, the biography of Nonnus caught the attention of a highly skilled forger, Konstantinos Simonides. Having counterfeited a papyrus that described Nonnus as a pagan poet who received baptism and dedicated himself to Christian literature, he tried to excite the curiosity of the first translator of Nonnus poetry into a modern language, the French Count de Marcellus. An analogous portrayal of the poets life is found in the short story The Poet of Panopolis by Simonides contemporary, Richard Garret. In it, the pagan Nonnus, unsatisfied with the poor reception of the Dionysiaca, decides to convert and amaze Christian readers with his Paraphrase. He also agrees to become a candidate for episcopacy in his hometown of Panopolis, incurring the wrath of the god Apollo, who, as a punishment, orders the repentant poet to publish the Paraphrase, which dooms him to lingering for perpetuity as an unsolvable enigma in the eyes of future generations. Nonnus is also the main character in the novel Im Garten Klaudias by the twentieth-century scholar Margarete Riemschneider. The poet goes here by the name of Ammonios, and it is only later that he is nicknamed Nonnus. Having finished his studies in Alexandria, Ammonios travels widely across the eastern parts of the Roman Empire, which allows him to witness historic events and collaborate with such important personalities of his day as Gregory of Nazianzus and Stilicho. Towards the end of his turbulent life, the poet, still as a pagan, finds refuge in the Egyptian monastery of Koptos, where over time he converts to Christianity, adopts the name of Nonnos and writes the Paraphrase.

It is readily noticeable that these reconstructions of Nonnus life have emerged from fascination not only with his oeuvre, but also with the world of Late Antiquity. That historical period, which started to be thoroughly studied only relatively recently, was long considered a period of the gradual decline of ancient civilization and culture, one that lacked originality when compared with earlier centuries. Today, however, it reveals itself ever more manifestly not as a world of despondent nostalgia for the glory of the classical past, but as one that boldly and consciously drew from earlier traditions and endowed them with new dimensions. It was a world where two great traditions, classical and Judaeo-Christian, were becoming inextricably intertwined, creating an entirely new quality. The elements that, on an equal footing, constituted the culture of Late Antiquity included Homeric epics and the Bible, mythological figures and Christian saints, Dionysus and Jesus. Despite the gradual Christianization of the Roman Empire, the classical heritage was certainly not disparaged; on the contrary, it was subject to reinterpretation and thrived as an integral part of everyday life. Without considering this context, one cannot fully understand Nonnus poetry.