Trends in Classics - Supplementary Volumes

Edited by

Franco Montanari

Antonios Rengakos

Volume

ISBN 9783110791815

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110791877

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110791969

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

The Orators and Their Treatment of the Recent Past

Trends in Classics Supplementary Volumes

Edited by

Franco Montanari and Antonios Rengakos

Associate Editors

Stavros Frangoulidis Fausto Montana Lara Pagani

Serena Perrone Evina Sistakou Christos Tsagalis

Scientific Committee

Alberto Bernab Margarethe Billerbeck

Claude Calame Kathleen Coleman Jonas Grethlein

Philip R. Hardie Stephen J. Harrison Stephen Hinds

Richard Hunter Giuseppe Mastromarco

Gregory Nagy Theodore D. Papanghelis

Giusto Picone Alessandro Schiesaro

Tim Whitmarsh Bernhard Zimmermann

Volume 133

The Orators and Their Treatment of the Recent Past

Edited by

Aggelos Kapellos

DE GRUYTER

ISBN 978-3-11-079181-5

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-079187-7

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-079196-9

ISSN 1868-4785

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022946559

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Editorial Office: Alessia Ferreccio and Katerina Zianna

Logo: Christopher Schneider, Laufen

Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck

www.degruyter.com

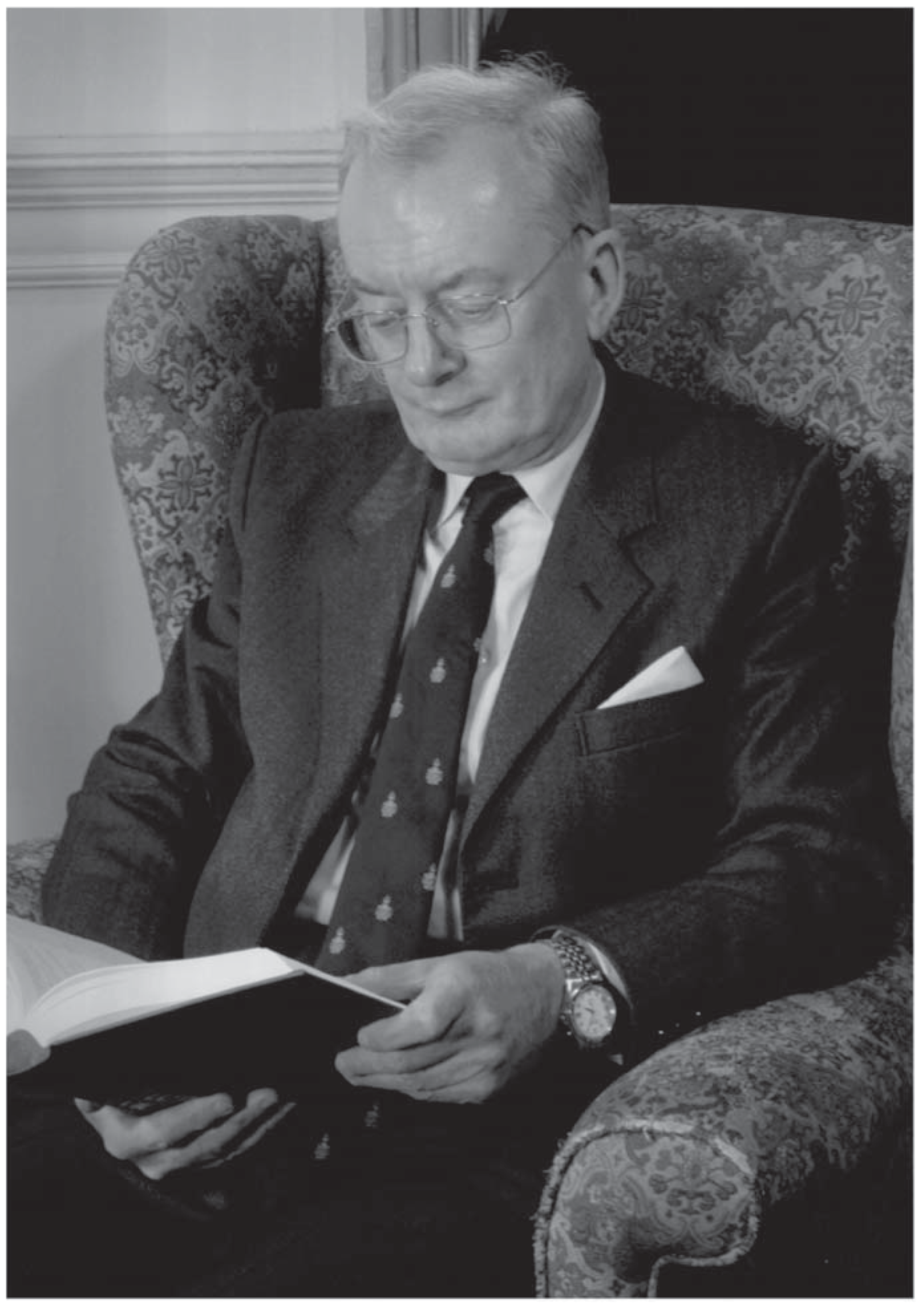

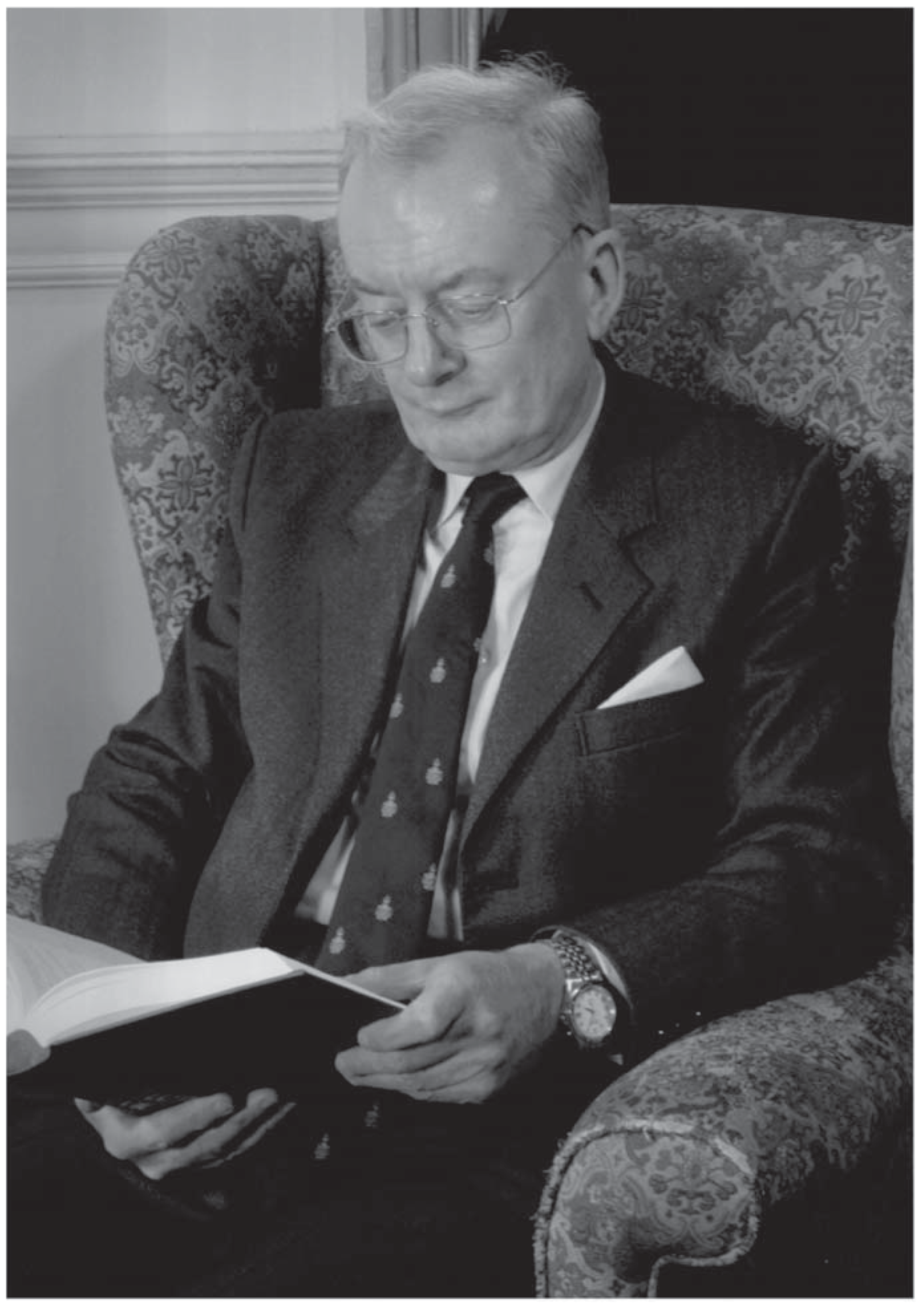

In memory of Peter Rhodes

Fig. 1: Peter Rhodes

The Orators and their Treatment of the Recent Past: Introduction

Aggelos Kapellos

The late Peter Rhodes had read a previous draft of my introduction. I heartily thank G. Martin, B. Cook, N. Crick, N. Siron, J. Roisman and the anonymous readers for their comments. For possible omissions or mistakes I am solely responsible.

The Athenian orators emphasized the importance of time () in their speeches.

Enquiry into the past and how this fitted to the present was not easy too. Reading the rhetorical corpus, we realize that there seems to be a trichotomy in the way the orators treated the past. There is:

(b) he middling past, about which an orator can say the older ones will remember and they can tell the younger. In 355/54 B.C. Demosthenes remembers in his speech Against Leptines how some brave Corinthians helped the Athenians, following their defeat against the Spartans near the Nemea river in 394, forty years earlier, and says that he is describing these events, relying on what he has heard from the older men among them ( ) (20.52).

And (c) the recent past, about which a speaker say that we/you all know. In 386 B.C. Platos Socrates says in his funeral speech in the Menexenus, supposedly delivered for those who had died in the Corinthian War, that he should not prolong the story of this war, because it is not a tale of ancient history about men of long ago ( ) (244d13).

This temporal distinction is artificial. Even though the orators usually acknowledge the division of the past into a mythical and historical period and distinguish between examples from the distant and the recent past, this distinction is never clear-cut, and the border between myth and history is rather fluid.

Nevertheless, the treatment of the three rhetorical periods of the past is not of equal weight in the orators. The distant past and myths loom large in the funeral speeches and in Isocrates oeuvre, but they are rarely referred to in symbouleutic and forensic speeches. In the latter the orators show a marked predilection for recent events, because they were considered more familiar, more

Taking into consideration the Greeks difficulty of conceiving the past, the orators trichotomy of time and their predilection for the recent past, this volume focuses on it and investigates the following issues: a) the time span of the recent past; b) the ability of the orators to interpret the recent past according to their interests; c) the inability of the Athenians to make an objective assessment of persons and events of the recent past; d) the unwillingness of the citizens to hear the truth, make self-criticism and take responsibility for bad results; and e) the superiority of the historical sources over the orators regarding the reliability of their historical precision. On the basis of these issues, in what follows: a) I try to explain the methodology that the contributors follow in approaching the recent past in the orators; b) I pinpoint the historical events and persons the orators are referring to in the speeches under investigation and c) I make a short presentation of the arguments of each chapter.

First, what needs further clarification is the time span that we could define as recent. Nouhaud distinguishes current events from historical ones He does this after a short discussion of the appeal to what the older ones will remember in the speech Against Leptines; so this twenty-year distinction is perhaps prompted by Demosthenes remarks. I agree with him. We saw above that Lycurgus mentioned the execution of Callistratus, not a recent event for the younger jurors, because it took place three decades before his speech, so we can say that this constitutes evidence of time that people could not hear as contemporary.

We saw earlier Gorgias positions about the past. What must be said now is that his positions were familiar to the Greeks of his day.

This does not mean that listeners passively accepted what speakers said about the recent past. On the contrary, they participated in the rhetorical reinterpretation of the past. Xenophon gives a clear example of this by reporting the reaction of Alcibiades supporters when he returned to the Peiraeus in 407 B.C. These men acted as if they were defending him in court, judging him in the light of recent victories. They claimed that his conduct of military affairs was excellent; they remembered his generosity towards the city through choregiai, trierarchies and taxes; argued that he had not wanted to profane the Mysteries; claimed that he went to Sparta against his will, foresaw the Athenian mistakes regarding the Sicilian expedition and believed that if he had remained in command of the fleet there it would have succeeded. However, they conveniently forgot that Alcibiades wanted to conquer Sicily and Carthage and that he considered himself socially superior to his fellow citizens; they deliberately forgot that they had helped unconsciously the sycophantic action of his enemies by not putting him on trial immediately, and thus they exculpated themselves from the responsibility for his unjust condemnation from the city. Moreover, they knew that no necessity had forced Alcibiades to flee to the Spartans and instruct them how to support Syracusan forces in Sicily and harm his city by fortifying Deceleia. Finally, nobody could know whether Alcibiades would have succeeded as a general in Sicily.