Unless noted otherwise, scriptural quotations are taken from the King James Version, with some modifications for accuracy or ease of comprehension. Psalm texts are taken from a draft translation of the Psalter, edited by Hieromonk Herman (Majkrzak) and Priest Ignatius Green, and used by permission; Psalms are cited according to the Septuagint (LXX) numbering, which differs from the Hebrew numbering (used by most English translations) in Pss 9147: LXX Ps 9 = Heb. Pss 910; LXX Pss 10112 = Heb. 11113; LXX 113 = Heb. 114115; LXX 114 = Heb. 16.19; LXX 115 = Heb. 116.1019; LXX 116145 = Heb. 117146; LXX 146 = Heb. 147.111; LXX 147 = Heb. 147.1220.

INTRODUCTION

T his book continues a series of investigations into the life and teaching of Jesus Christ.

The foundational principle of most such investigations is often chronology; that is, the events in the life of Jesus are examined in a chronological order that is determined by the harmonization of the accounts of the four Gospels. Another equally widespread approach is a systematic analysis of the material found in each of the four Gospels, or one of them. There is a third approach, which divides all the material in the Gospels thematically. Consequently, all the parables of Jesus are treated separately, then all his miracles, then the history of the Passion. This is the foundational approach of this series of books, titled Jesus Christ: His Life and Teaching. Each theme is treated in a separate volume.

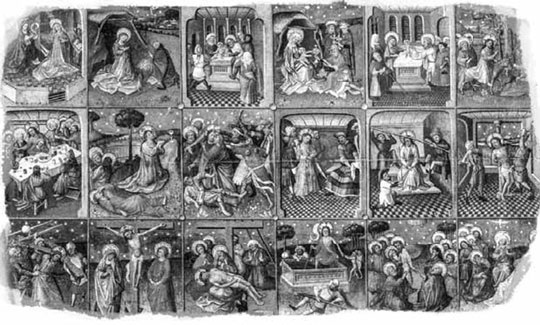

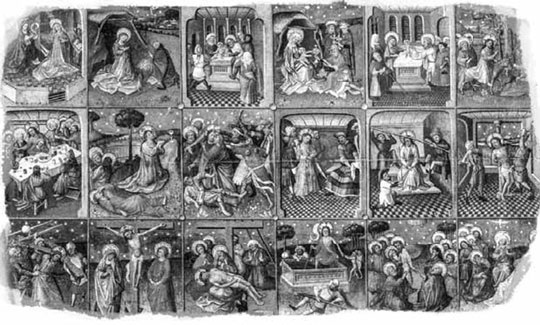

The Passions, Anonymous artist, 15th century

In the first volume of this series, we summarized the general principles that lie at the foundation of this investigation; we informed the reader of the most important directions in contemporary New Testament scholarship; and we treated the Gospels as the primary source of our knowledge about Jesus. Finally, we examined the introductory chapters of all four Gospels and underlined the essential themes to be fully treated in the subsequent volumes.

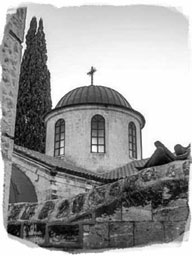

Dome of an Orthodox church in Cana of Galilee

The second volume was dedicated to the Sermon on the Mountthe longest public address of Jesus included in the Synoptic Gospels. In it, he formulated the fundamental principles of his moral teaching, his view concerning certain prescriptions of the Law of Moses, the qualities that his followers must acquire, as well as his teaching concerning fasting, prayer, and almsgiving.

This third volume is dedicated to the miracles of Jesus, as described in the four Gospels.

The miracles are the aspect of Jesus Christs activity that inspired the greatest interest of his contemporaries. Crowds of people, attracted by his fame as a healer, surrounded him, no matter where he went. Even in the first stages of his public ministry in Galilee, And his fame went throughout all Syria: and they brought unto him all sick people that were taken with divers diseases and torments, and those which were possessed with demons, and those which were epileptic, and those that had the palsy; and he healed them. And there followed him great multitudes of people from Galilee, and from Decapolis, and from Jerusalem, and from Judaea, and from beyond Jordan. (Mt 4.2425) With time, his fame only grew, and some of the people he healed, among them women, joined the number of his disciples (see Lk 8.23).

If we were to follow the generally accepted chronology that is based on the Gospel of John, then all the miracles of Jesus, except for the very first one (transforming water into wine at the wedding in Cana of Galilee) were accomplished in the space of three yearsbetween the first and fourth Passovers of his public ministry.

By what principle did the evangelists choosefrom the vast multitude of miracles performed by Jesusthe ones that they include in their accounts? We can only guess that they chose first of all those miracles that were memorable for their vibrancy and unexpectedness, for example the calming of the storm, walking on water, and casting out the legion of demons from the possessed man. One or another of the events could have been chosen if the healed person was not simply one of the many sick in the crowds who came to Jesus in tens and hundreds, but a memorable figure. For example, he may have begun a dialogue with Jesus (such as the centurion from Mt 8.513 and Lk 7.110), or the apostles may have paid special attention to him (for example, the man born blind from birth in Jn 9.17), or he may have returned to give thanks to Jesus (for example, one of the ten healed lepers in Lk 17.1219). Some miracles were mentioned because they occurred on the Sabbath, when Jesus attended the synagogue, which often incited the anger of the Jews (in such miracle accounts, the evangelist often describes the miracle, then recounts Jesus dialogue with the Jews). Finally, the evangelists pay special attention to the miracles that were performed for individuals of a different ethnicity or religious confession, such as the Canaanite (or Syrophoenician) woman, the Samaritan woman, and the centurion.

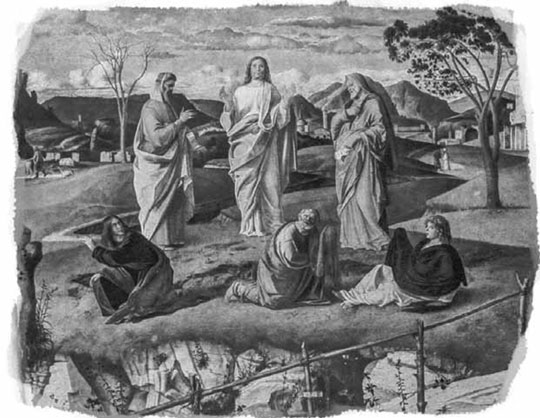

The Transfiguration, Giovanni Bellini, 148085.

In this book, the story of Jesus Christs miracles will be preceded by an introductory section, in which we will examine the phenomenon of miracles from a scientific and historical point of view, analyzing the arguments of those who reject the possibility of miracles on the basis of reason. Then, we will speak of the miracles of the Old Testament prophets, after which we will attempt to systematically analyze the miracles contained in the four Gospels.

Chapter 1

THE MIRACLE AS A RELIGIOUS PHENOMENON

T he generally accepted definition of miracle is that it is a phenomenon that transcends the laws of nature and is, therefore, supernatural. When analyzing and interpreting a miracle, the worldview of the person approaching this phenomenon is key.

Confucius

There is a widely held opinion that in the ancient world, faith in miracles was universal, and only in modern times, under the influence of scientific progress, did this faith waver. Some also assert that faith in miracles is a defining characteristic of all religious traditions, while only the irreligious deny the possibility of miracles. But in ancient times, faith in miracles was by no means universal. And by far not all religious traditions consider miracles to be a necessary attribute of faith and holiness. The founders of three world religionsConfucius, Buddha, and Muhammadwere skeptical or even disparaging of miracles, even if, after their deaths, stories of their own lives were elaborated with miraculous details.