ALLEN S. WEISS

Copyright Allen S. Weiss 2013

The publishers would like to thank The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation for its support in the publication of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

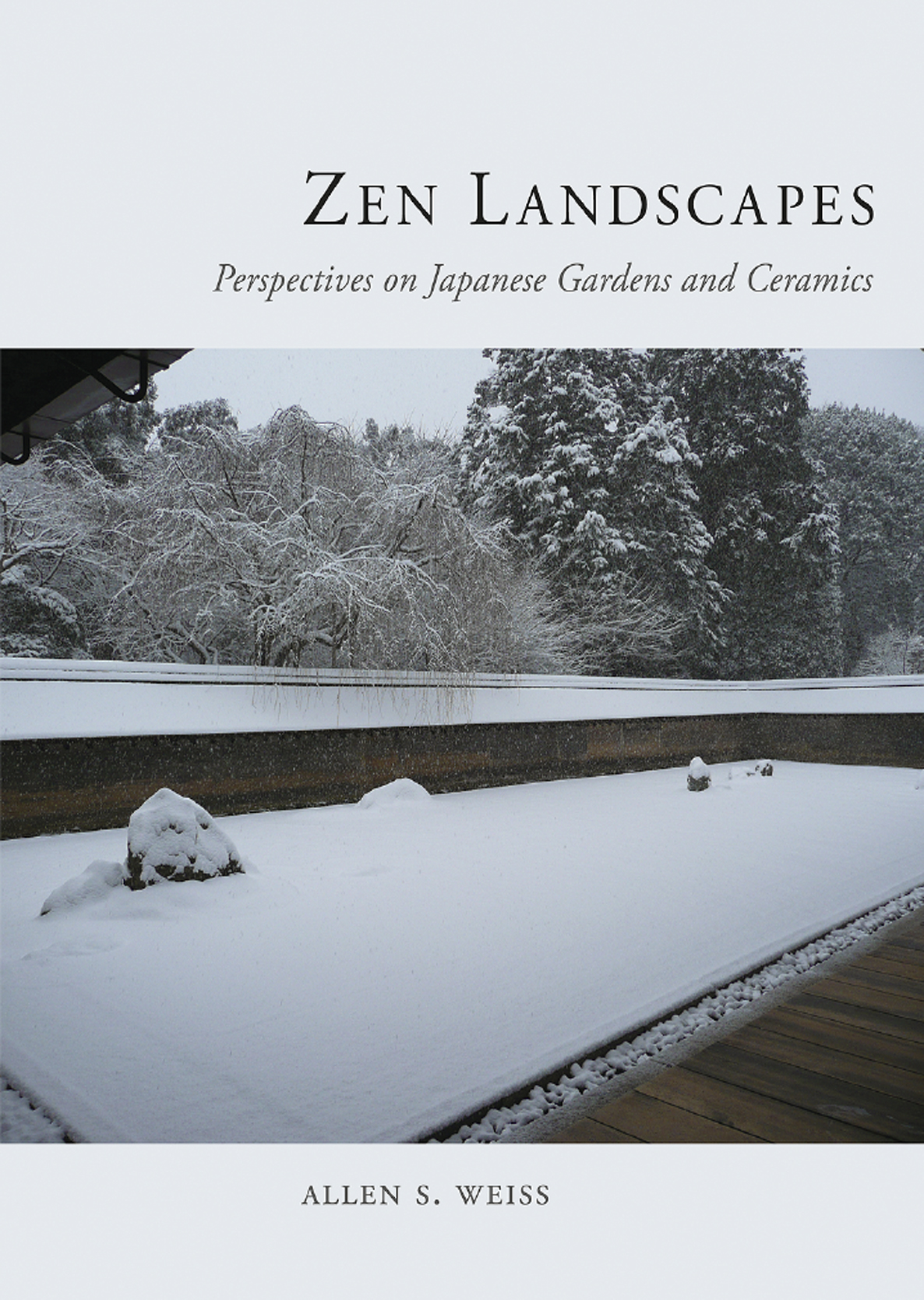

Ryan-ji, Kyychi pond.

Ryan-ji, snowstorm of 31 December 2010.

INTRODUCTION

T RANSFORMATIONS OF V ISION

T he dry garden of Ryan-ji in Kyoto is one of the most analysed and photographed works of art in the world. Thus, well before my first visit in November 2006, I felt I knew the garden intimately, and was thoroughly prepared to elaborate on the knowledge I had attained from dozens of books and hundreds if not thousands of images. As soon as I stepped onto the veranda of the temple overlooking the garden, I was stupefied, first by its sublime beauty and soon afterwards by the fact that it hardly corresponded to any description I had read of it. How could this be? Could all previous commentators have been so wrong? Could I have been so blinded by my own prejudices and paradigms? Could I have fallen into the textual trap of confusing image and description for the garden itself? Certainly my attraction to Japanese dry gardens stems from the fact that they corroborate my aesthetic principles, wishes and utopias. But might this passion, hitherto untested against its objects, have falsified my vision? I immediately suspected that my disorientation went far beyond mere culture shock. With each discovery about Japanese culture, my bewilderment seemed to multiply even as my knowledge expanded, and I seemed further from aesthetic enlightenment than ever, as Ryan-ji led me to consider other art forms and other viewpoints: the stones had their antecedents in Chinese and Japanese painting; the surrounding walls evoked unglazed pottery surfaces; the stone borders hinted at the complicated issues of inside and outside in Japanese architecture; the sparse moss suggested the need for water in an otherwise dry garden, thus pointing to the essential role of atmospheric effects in Japanese art; the raked gravel stressed the role of stylization and stereotype in image and word; and the overhanging cherry tree evoked the crucial interpenetration of art and world. I was to discover that these correspondences were not mere free associations, but are deeply ingrained in Japanese aesthetics. After nearly two decades of meditation on Western gardens and landscape from the

As a result I offer here a certain number of principles, composed in the form of a Manifesto for the Future of Landscape, to give a sense of my attitudes and hopes often against the grain of contemporary theory and practice regarding landscape creation, appreciation and conservation.

1. The garden is a symbolic form, which suggests that symbols are as important as images to guide appreciation as well as restoration. The garden is earthly, but it also reaches to the heavens, and occasionally to the underworld.

2. The garden is never merely a picture, and the ground plan is usually misleading. The spatiality of gardens is plastic and dynamic, such that kinetics is of the essence. The garden is thus a synaesthetic matrix.

3. The garden is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a web of correspondences, a site that should encompass all the arts. Consequently, every garden must be continuously reinvented as a scene for contemporary activities.

4. The garden is simultaneously a hermetic space and an object in the world. Thus the formal garden must remain open to the informality of nature. Garden closure is a sociological and psychological phenomenon, not an ontological one.

5. The garden is a paradox, necessitating that complexity and contradiction should not be avoided, since the finest metaphors are often unstable and equivocal.

6. The garden is a narrative, a transformer of narratives, and a generator of narratives, such that a garden is all that it evokes. Consequently, tales and symbols are an integral part of gardens.

7. The unpeopled garden is either an abstraction or a ruin, suggesting that all aesthetic value has a use value that must be respected. The most complex landscape is the one most closely observed.

8. The garden is a memory theatre, which must bear vestiges of its sedimented history, including traces of the catastrophes that it has suffered. In the history of landscape, accidents are not contingent, but essential.

9. The garden is a hyperbolically ephemeral structure. Anachronism is of the essence, since a garden is all that it was and all that it shall become.

Ryan-ji, snowstorm of 31 December 2010.

Ultimately, every artwork bears its own phantasmic ontology, which must be distinguished from the cultural forms and symbols that ground the work. Throughout history and across cultures, the forms of and relations between representation and vision are constantly changing. Our ways of seeing must be no less adaptable, subtle and inventive.

THE FORMAL STAGING of the Japanese aesthetic sensibility is centred on the Zen-inspired tea ceremony, a sort of Gesamtkunstwerk which links painting, calligraphy, pottery, lacquer, woodcraft, architecture, design, poetry, cuisine, flower arranging, gardens and the gestural choreography of the ceremony itself in a highly ritualized event. Here, every art form informs all other art forms, and appreciation is a global experience. As Christine M. E. Guth explains:

The true man of tea is measured by the skill with which he combines articles from his collection so that they form a harmonious ensemble in the tea room. This process, known as tori awase (selecting and matching), requires broad cultural knowledge, connoisseurship, and creativity. The host must consider the context: the season, the occasion, and the identity of the guest or guests. He must take into account the size, shape, texture, color, and material of each work of art... Although he must also keep in mind historical connotations such as the origins, history of ownership, and previous use of each article, he must use this knowledge creatively, so as to make each gathering a unique and memorable experience.