Jen Kuzara: Your feedback was especially precise and your feminist perspectives, extremely valuable. Benjamin Purzycki: Thank you for your thoughtful input from cover to cover, for your encouragement, and for our engaging conversations.

Erin: No one helped me as much or in so many ways as you. Your editing was not only tireless and brilliant, but given with such inspiration that you made the strenuous process of writing a book a breathtaking, contemplative journey. This book, and the growth it afforded me, would not be possible without you.

My father: You sat me down at a very young age and taught me biology, evolution, and defiant intellectualism. Your history, your heritage, and your resistance to the abuse of power live on in the pages of this book.

Lastly, I thank all the great thinkers who have come before. You form the bedrock on which all of science is built. Your fire, your vision, and your great personal risks are not forgotten.

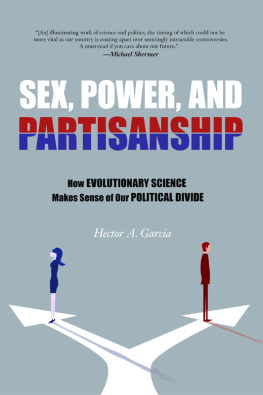

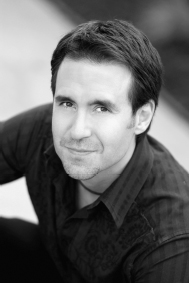

HECTOR A. GARCIA, PsyD, is an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and a clinical psychologist at the Veterans Health Administration specializing in the treatment of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He has published extensively on the treatment of PTSD in combat veterans. He has also published on the masculine identity in the aftermath of war, stress, and rank in organizations, and the interplay between religious practice and psychopathology.

If oxen and horses and lions had hands and were able to draw with their hands and do the same things as men, horses would draw the shapes of gods to look like horses and oxen to look like oxen, and each would have made the gods bodies to have the same shapes as they themselves had. Xenophanes (ca. 570ca. 478 BCE)

What is God? Many would say that God is love, or God is beauty. For others, God is an immaterial being, the creator of the universe. God has been described as compassionate and merciful, as the ultimate moral authority, or the ultimate source of goodness in the world. The pious draw from this vision of God a sense of awe, purpose, hope, and empathy. From this vision, masses of people around the world convene around a shared sense of wonder, appreciation, and unity, and they cultivate between one another an environment of kindness, generosity, and support. This vision of God is indisputable, insofar as it forms the phenomenology of the religious worship of God.

But there is another vision of God that is just as real. The majority of the world's believers worship a god that is fearsome and male, and his portrayal demands reckoning. Scripture depicts this god as one who rains fury upon his enemies and slaughters the unfaithful. It also shows him policing the sex lives of his subordinates and obsessing over sexual fidelity. Extremists, drunk on this vision, steer airplanes into buildings or obliterate themselves in crowded marketplaces. They foment sexual shame and engage in genital mutilation, acid attacks, and so-called honor killings. They start inquisitions and witch hunts, religious wars and religious conquests. They seize ideological control and breed superstition, ignorance, and prejudice. And they also seek to enforce a prohibition against questioning God, leaving such inhumanities unexamined, sometimes for fear of the treatments just described.

Critically, we now live in an age in which religions clash with women's rights as gender equality strains against its margins, in which theocratic regimes are gaining control of nuclear arms, and in which dangerous fundamentalism is increasingly taking hold around the world. This is a crucial moment for us to force the wedge of inquiry, if only to better understand the means by which religion may be used to encourage what is worstrather than what is bestin human nature.

We may begin by questioning whether there is something common to the perpetrators of the kinds of violence and oppression listed above. The seemingly obvious answer is that these acts are almost exclusively committed by men. In the rare instances where they are committed by women or children, the acts are almost always influenced or coerced by men. This is an important starting point. Since another common root to these acts is purported religiosity, a second key question becomes, is there something common to the vision of God behind them? Here we arrive at the crux of the matter: the common vision is that of God as man.

I argue here that God was created in the image of man. This argument is not new. The epigraph of this chapter would suggest that thinkers have made this connection since at least the time of the ancient Greeks. However, there are good reasons not only to emphasize that God was created in the image of man, rather than the other way around, but also to study the dominance characteristics portrayed in Godmost notably because men of power have historically conflated themselves with God in order to secure more power and have used this power to enact further violence and oppression. This pattern has emerged again and again across religious history as men have summoned divine legitimacy to justify their worst impulses. God himself is frequently portrayed as engaging in violent acts, thus serving to validate the destructive actions of the powerful.

This is most evident among the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), whose scriptures all too frequently depict a despotic male god. The Abrahamic god is the most widely worshipped man-based god, with followers comprising over 50 percent of the world's religious practitioners.humans. I will thus occasionally reference male gods from other religions to illustrate how consistently male-typical patterns of dominance traverse traditions of faith. Even so, the Abrahamic god will remain my focus here, if only because He is by far the most globally dominant.

To understand such a god, we must first understand the minds of men, for it is these minds that think up ways to oppress and kill. Arguably the best way to understand the ultimate basis for male violence and oppression is through the evolutionary sciences. Such disciplines reveal the ancient underlying motivations for violence and oppression, molded as they were by the process of natural selection. The patterns of behavior such motivations were passed on by our primate ancestors and are easily evidenced in living nonhuman primatesour closest living relatives. Despite his upright stance, his clothes, and his sometimes-good table manners, man rarely surpasses his most primal impulses. Accordingly, men often seek out dominance in the manner of male apes, using violence to obtain evolutionary rewards such as food, territory, and sex. Humankind may have managed to create things like tools, weapons, and religions, but we remain one species of great ape that emigrated from Africa.

This can be difficult for many people to hear because as humans we have a tendency to think of ourselves as unique and to hold ourselves above other species. But we have DNA like all other life-formswhich ultimately shapes or brains and influences the manner in which we thinkand we share as much as 99 percent of our DNA with nonhuman primates. And like other animals, we are organic beings that live, eat, reproduce, and die. As such, we require things like food, sex, and territory to fulfill our organismic destinies. None of this should be surprising.

Next page