Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my own little infidels, Alexandra and Raymond

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2014 by Brian A. Catlos

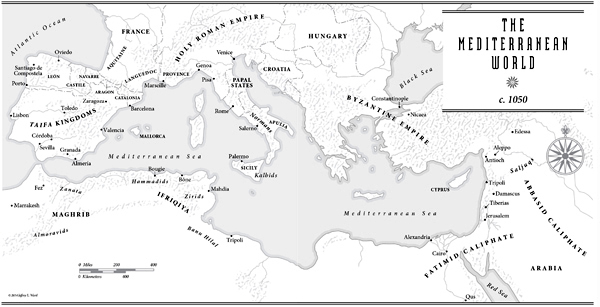

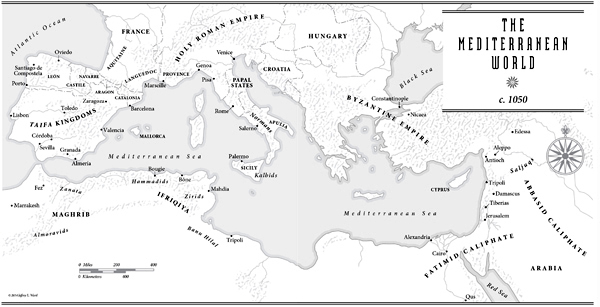

Map copyright 2014 by Jeffrey L. Ward

All rights reserved

First edition, 2014

Owing to limitations of space, illustration credits can be found at the back of the book.

eBooks may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases, please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department by writing to MacmillanSpecialMarkets@macmillan.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Catlos, Brian A.

Infidel kings and unholy warriors: faith, power, and violence in the age of crusade and jihad / Brian A. Catlos. First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8090-5837-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-374-71205-1 (ebook)

1. Mediterranean RegionHistory4761517. 2. Crusades. 3. CrusadesInfluence. I. Title.

DE94.C37 2014

909.07dc23

2013043160

www.fsgbooks.com

www.twitter.com/fsgbooks www.facebook.com/fsgbooks

Map: The Mediterranean World, c. 1050

A Note on Sources

Every historical narrative is the product of a series of deliberate choices and interpretations on the part of the historian, irrevocably imbued with his or her own subjectivity and biases. But this is not to say that history is fiction, or that a historian should arbitrarily choose evidence that suits an intellectual, personal, or political agenda. Historians are bound to seek out, read, and analyze all the material relevant to the subject they are studying, and to make their interpretations in good faith, based on accepted principles of weighing and analyzing evidence, and to guard against the intrusion of their own prejudices. In a book intended for a narrow scholarly readership, all of this would be laid bare in an interminable series of footnotes and technical digressions. Conflicting evidence would be discussed, substantial interpretative decisions would be explained, and the full range of source material for each significant event would be cited. What makes for good science, however, does not necessarily make for good reading, just as seeing how sausage is made does not necessarily make one hungry. With that in mind, I have not cited the long list of works and sources that I consulted for each of the chapters. Instead, I have included references only for those passages taken directly from contemporary sources. I also provide, in the back of the book, a short overview of the relevant historical literature, for those who would like to explore the Mediterranean world of 10501200 in more detail.

A Note on Names

Our custom of using a first name followed by a surname is a relatively new development, and one that until recently was particular to the cultures of Western Europe. In the Middle Ages, names functioned somewhat differently. First names tended to be scriptural in origin, but nonbiblical names were popular, especially among Christians, who drew on Latin and Greek (Philip, Andronikos) and Persian (Vahram) culture, or Germanic rootsWilliam, Richard, Alfonso, Bohemond, and so on. Muslims and Jews sometimes also used nonreligious names, whether Berber (Tashufin), Persian, Turkic, classical (al-Iskander, or Alexander), or Aramaic (Hasdai or Hasday).

A common way of forming a last name was to use a patronymic. Who your father was was perhaps the most important piece of information about you: it indicated your social class, power, and wealth. The Arabic ibn (abbreviated as b. ) and Hebrew ben mean son of (or bint , daughter of, for women). Yusuf b. Tashufin was Yusuf, son of Tashufin, and might be known simply as Ibn Tashufin. In Latin lands, the genitive construction (the suffix -is , which means of) was prevalent. Thus, Sisnando Davdez meant Sisnando, [son] of David. Some Berbers, alternatively, traced their ancestry through the female line. By stringing together a series of patronymics, Muslims and Jews created names that acted as genealogies. The Christians of the borderlands often imitated these naming conventions: the brother and antecessor of Alfonso the Battler, King Pedro I of Aragon, for example, signed his name in Arabic as Bitr ibn Shanja (Peter, son of Sancho), using shaky Arabic script.

Last names were also sometimes taken from places. Robert Guiscard and Roger of Sicily and their descendants were known as dHauteville in reference to their ancestral home. The Cid was Rodrigo Daz del Vivar because his hometown was Vivar. The Islamic system used by both Muslims and Jews resulted in similar names. Al-Qurtubi refers to someone from Crdoba, al-Siqilli to someone from Sicily, al-Mahdiyya to someone from Mahdia, and al-Misri to someone from Cairo. Because tribal and clan affiliation remained important in much of the Islamic world, these were also used in naming; any member of the Zirid clan, for example, might be referred to as al-Ziri. Non-Muslims often used names that referred to their ethnic origin or religious community: al-Nasrani (the Nazarene, or Christian), al-Yahudi (the Jew), or al-Armani (the Armenian). The name of an early or famous ancestor could also come to serve as a family name. Any of Salah al-Dins descendants could take the name al-Ayyubi, after Salah al-Dins father, Ayyub.

Prominent individuals often took honorific names based on an illustrious deed or a physical attribute, or as an ideological advertisement. Roger of Sicilys oldest brother was known as William Iron Arm, while Nur al-Dins father, Zengi, took the title Imad al-Din, Pillar of the Faith, to reinforce his political-religious image. People of humbler origins often identified by the trade they or their families practiced; the name Ferrer means blacksmith, al-Najjar is carpenter.

One naming element was unique to the Islamic world and was used by both Jews and Muslims: the filionymic. Abu means father, and men could be referred to as Abu so-and-so, either in reference to their firstborn or a famous son, or the son they were expected to have. A firstborn son was usually named after the paternal grandfather, so a young boy named Hisham whose father was named Abd Allah could be called simply Abu Abd Allah. The Jewish wazir of Granada, Ismail ibn Naghrilla, was referred to as Abu Ibrahim by his Muslim supporters, out of respect.

Since every other name an individual was given or acquired served as an adjective, in Christian, Muslim, and Jewish cultures, what mattered most was the first name. The caliph Abd al-Rahman III could use his name to show his descent from the first Umayyad amir of al-Andalus: Abd al-Rahman b. Muhammad b. Abd Allah b. Muhammad b. Abd al-Rahman b. Hakam b. Hisham b. Abd Allah al-Dhakil. Or he could go as Abd al-Rahman, or as Ibn Muhammad, or as Abu Hisham (after his son), or by his honorific al-Nasir li-Din Allah (the Victorious by God in Gods Faith)but never as Abd or as Rahman, which are only parts of his first name.