Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Stephanie Tollis, Loretta Damron, and Ellen Dougherty for acquiring and preparing illustrations. We are also grateful to David Orsinelli, Steven Cassidy, Stephen Sawada, Elisa Bradley, Dean Boudoulas, Scott Lilly, and Clifford Cua for providing some of the illustrations. We also recognize Kristin Kalasho for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Chapter 1

History of Echocardiography

Harvey Feigenbaum

Many histories of diagnostic ultrasound, and cardiac ultrasound in particular, have been written. an American engineer, began to apply this technique and received a patent. It is this flaw detection technique that ultimately was used in medicine.

An Austrian, Karl Dussik,

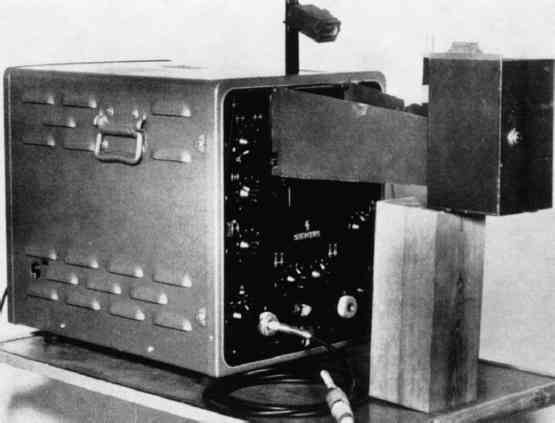

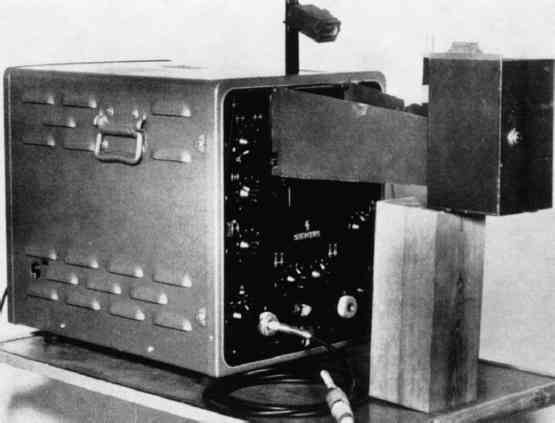

The original instrument ( was the detection of mitral stenosis. He noted that there was a difference between the pattern of motion of the anterior mitral leaflet in patients who did or did not have mitral stenosis. Thus, the early studies published in the mid-1950s and early 1960s primarily dealt with the detection of this disorder.

The work being done in Sweden was duplicated by a group in Germany headed by Dr. Sven Effert. also wrote a large review of cardiac ultrasound as a supplement to Acta Medica Scandinavica, which was published in 1961, and remained the most comprehensive review of this field for more than 10 years. In the movie and the review, Edler and his coinvestigators described the ultrasonic techniques for the detection of mitral stenosis, left atrial tumors, aortic stenosis, and anterior pericardial effusion.

FIGURE 1.1. Ultrasonoscope initially used by Edler and Hertz for recording their early echocardiograms. (From Edler I. Ultrasound cardiography.

Acta Med Scand Suppl 370 1961;170:39.)

Video 1-1

Despite their initial efforts at using ultrasound to examine the heart, neither Edler nor Hertz really anticipated that this technique would flourish. Helmut Hertz was primarily interested in being able to record the ultrasonic signals. In the process, he developed ink-jet technology and spent only a few years in the field of cardiac ultrasound. He devoted most of the rest of his career to ink-jet technology, for which he held many important patents. He also advised Siemens Corporation, which provided its first ultrasonic instrument, that it should not enter the field of cardiac ultrasound because he personally did not feel that there was a great future in this area (Effert, personal communication, 1996). Edler too did not develop any further techniques in cardiac ultrasound. He retired in 1976 and until then was primarily concerned with the application of echocardiography for mitral stenosis and, to a lesser extent, mitral regurgitation. He never became involved with any of the newer techniques for pericardial effusion or ventricular function.

China was another country where cardiac ultrasound was used in the early years. In the early 1960s, investigators both in Shanghai and Wuhan were using ultrasonic devices to examine the heart. They began initially with an A-mode ultrasound device and then developed an M-mode recorder.

In the United States, echocardiography was introduced by John J. Wild, H. D. Crawford, and John Reid,

I became interested in echocardiography in the latter part of 1963. While operating a hemodynamic laboratory and becoming frustrated with the limitations of cardiac catheterization and angiography, I saw an advertisement from a now defunct company that was claiming that it had an instrument that could measure cardiac volumes with ultrasound. This claim ultimately proved to have no basis. However, when I first saw the ultrasound instrument displayed at the American Heart Association meeting in Los Angeles in 1963, I placed the transducer on my chest and saw a moving echo, which had to be coming from the posterior wall of my heart. This signal undoubtedly was the same echo that Hertz and Edler had noted approximately 10 years earlier. I had the people from the company explain the principles by which such a signal might be generated. I asked them whether fluid in back of the heart would give a different type of a signal, and they said that fluid would be echo free. When I returned to Indiana, I found that the neurologists had an ultrasonoscope that they used for detecting the midline of the brain. Fortunately for me, the instrument was rarely being used and I was able to borrow it. I proceeded to examine more individuals, and again I was able to record an echo from the back wall of the left ventricle. I looked for a patient with pericardial effusion. As predicted, there were now two echoes separated by an echo-free space. The more posterior echo no longer moved, whereas the more anterior echo moved with cardiac motion. We went to the animal laboratory to confirm these findings and thus began my personal career in cardiac ultrasound. This initial paper on pericardial effusion was published in JAMA in 1965.

Although this phase of the history of echocardiography is commonly considered the origins of the early practice of echocardiography, it should be mentioned that Japanese investigators were working simultaneously using ultrasound to examine the heart. In the mid-1950s, several Japanese investigators such as Satomura, Yoshida, and Nimura at Osaka University were using Doppler technology to examine the heart. They began publishing their work in the mid-1950s. These efforts laid the basis for much of what we do today with Doppler ultrasound.

The field of cardiac ultrasound has evolved with the efforts of numerous individuals over the past 50 years. This development is an outstanding example of collaboration among physicists, engineers, and clinicians. Each of the cardiac ultrasonic techniques has its own individual history. Even the name echocardiography has a story of its own. Edler and Hertz first called this technique ultrasound cardiography with the abbreviation being UCG. Ultrasound cardiography was a somewhat cumbersome name. The most common use of medical diagnostic ultrasound in the late 1950s and early 1960s was an A-mode technique to detect the midline of the brain. This midline echo would shift if there were an intracranial mass. The technique was known as echoencephalography, and the instrument was an echoencephalograph. It was such an instrument that I borrowed from the neurologists. If the ultrasonic examination of the brain is echoencephalography, then an examination of the heart should be echocardiography. Unfortunately, the abbreviation for an echocardiogram would be ECG, which was already preempted by electrocardiography. We could not use the abbreviation echo because it did not differentiate from an echoencephalogram. The reason the term echocardiography finally caught on was because echoencephalography disappeared. No other diagnostic ultrasound technique used the term echo except for the examination of the heart. So, the abbreviation echo now stands only for echocardiography and is not confused with any other ultrasonic examination.

DEVELOPMENT OF VARIOUS ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC TECHNOLOGIES

DEVELOPMENT OF VARIOUS ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC TECHNOLOGIESThe story of echocardiography involves the evolution and development of its many modalities such as A-mode, M-mode, contrast, two-dimensional, Doppler, transesophageal, and intravascular applications. The Doppler story is truly lengthy and international. The Japanese began working with Doppler ultrasound in the mid-1950s. demonstrated that one could derive hemodynamic information from Doppler ultrasound. They noted that one could use a modified version of the Bernoulli equation to detect gradients across stenotic valves. The report that the pressure gradient of aortic stenosis could be determined with Doppler ultrasound was probably the development that established Doppler echocardiography as a clinically important technique.

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 FIGURE 1.1. Ultrasonoscope initially used by Edler and Hertz for recording their early echocardiograms. (From Edler I. Ultrasound cardiography. Acta Med Scand Suppl 370 1961;170:39.)

FIGURE 1.1. Ultrasonoscope initially used by Edler and Hertz for recording their early echocardiograms. (From Edler I. Ultrasound cardiography. Acta Med Scand Suppl 370 1961;170:39.)

DEVELOPMENT OF VARIOUS ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC TECHNOLOGIES

DEVELOPMENT OF VARIOUS ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC TECHNOLOGIES