William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Text Mary Colwell, 2018

Illustrations Jessica Holm, 2018

Curlews A.W. Bullen first published on https://hellopoetry.com/. Reproduced by permission.

Messengers of Spring Kerry Darbishire, 2017, Curlew Calling: An Anthology of Poetry, Nature-Writing and Images in Celebration of Curlew, edited by Karen Lloyd. http://karenlloyd-writer.co.uk/curlew-calling-anthology/. Reproduced by permission.

Love and Revolution Alastair McIntosh, 2006, Luath Press, Edinburgh. Reproduced by permission.

Death of a Naturalist, Faber & Faber Ltd Seamus Heaney, 1966. Reproduced by permission.

The Hounds of Hell John Masefield, 1920. Permission to reproduce granted by The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of John Masefield.

Incoming, Curlew Calling: An Anthology of Poetry, Nature-Writing and Images in Celebration of Curlew, edited by Karen Lloyd Jonathan Humble, 2017. http://karenlloyd-writer.co.uk/curlew-calling-anthology/. Reproduced by permission.

The author asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008241070

eBook Edition April 2018 ISBN: 9780008241063

Version: 2019-03-05

Curlew Moon is dedicated to my two sons, Dom and Greg, who were bemused by the idea of walking 500 miles for curlews, but actually think its quite cool.

Contents

Chapter 1

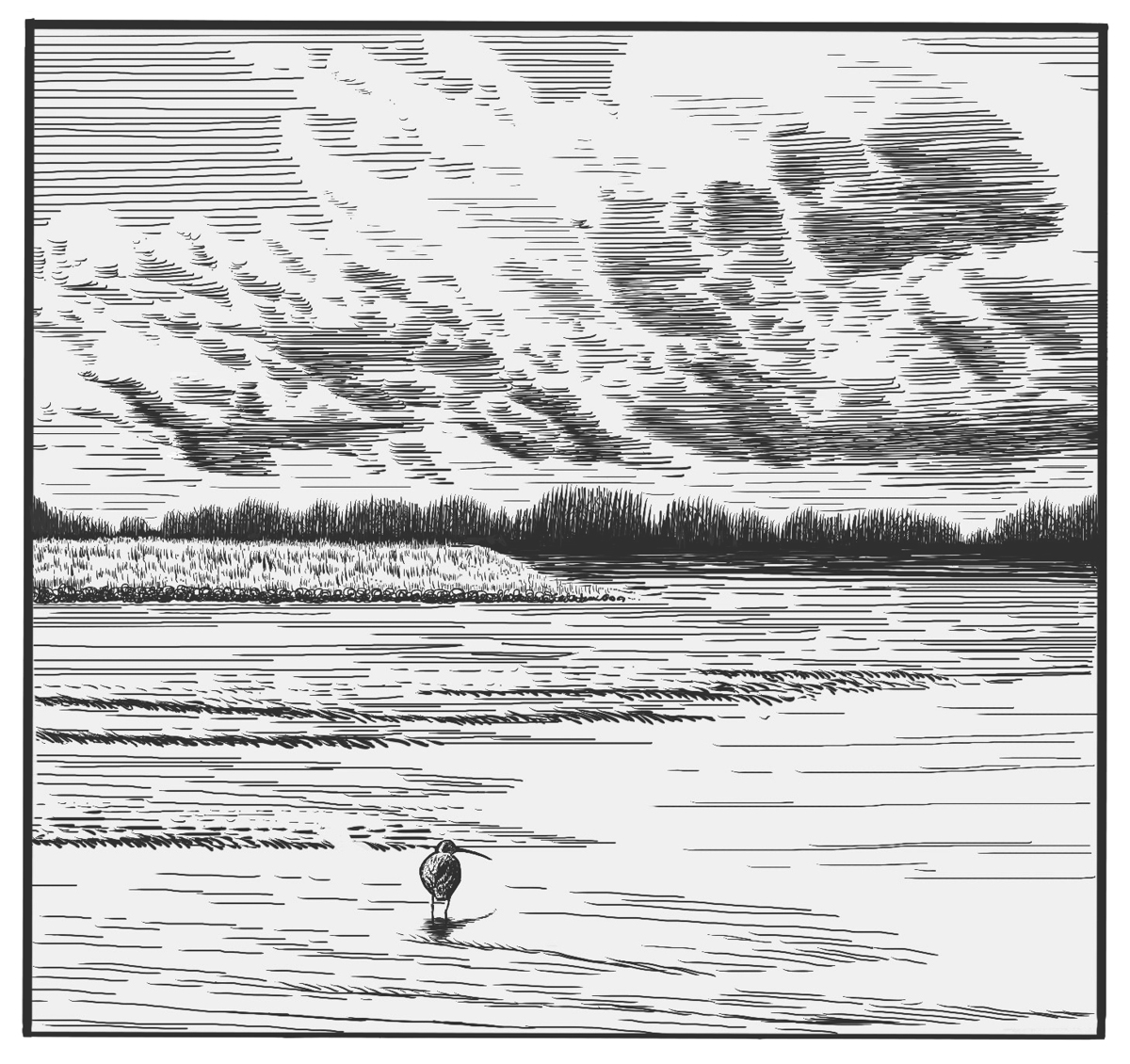

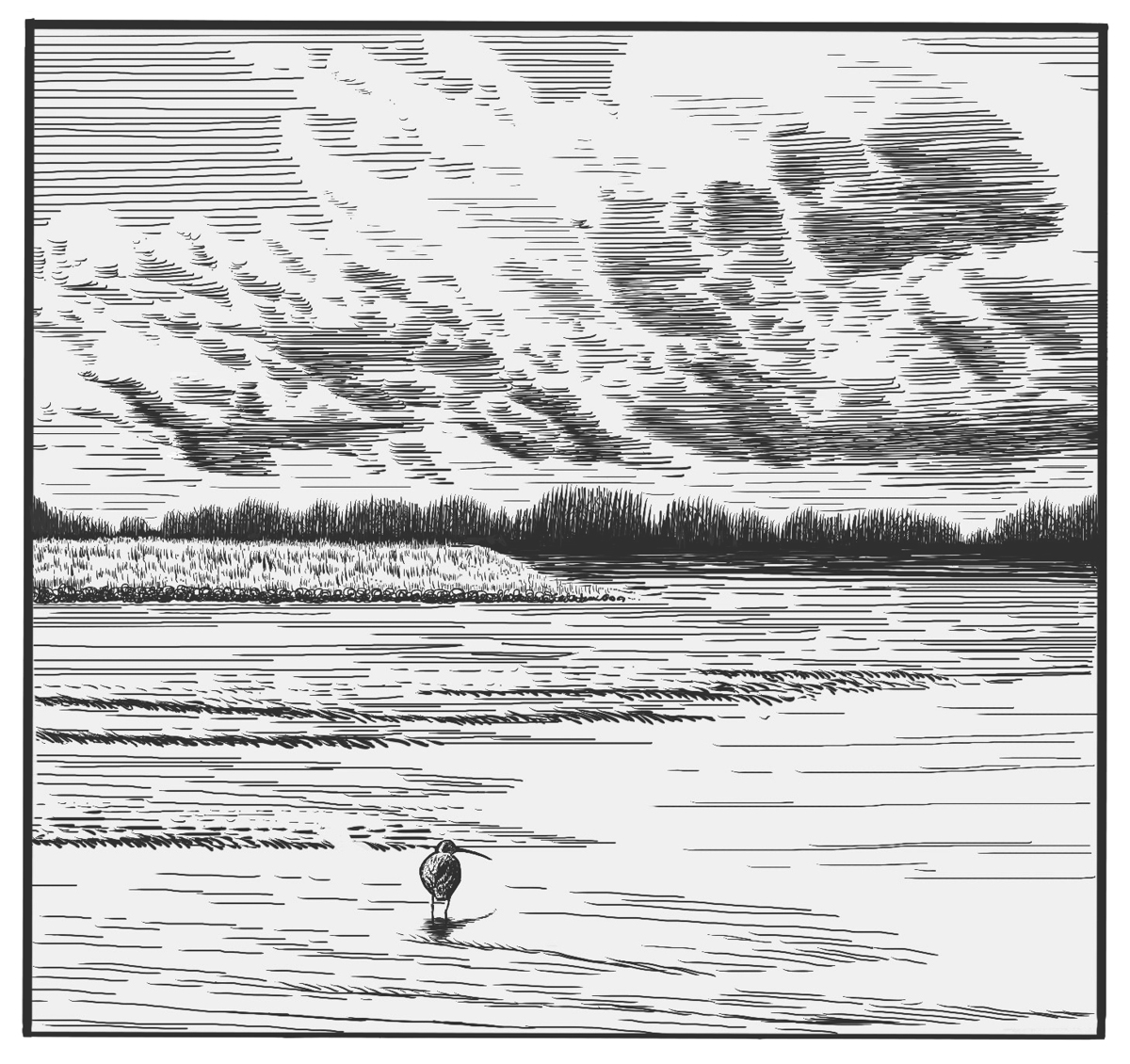

There is a wildlife spectacle that can transport the soul to a place of yearning and beauty, to an experience that has inspired generations of thinkers and dreamers. Imagine, if you will, a blustery cold day in December. Bitterly cold. A bird stands alone on the edge of a mudflat, some distance from where you are standing. Its silhouette is unmistakable. A plump body sits atop stilty legs. The long neck arcs into a small head, which tapers further into an extended, curved bill. The smooth, convex outlines of this curlew are alluring. They touch some ancestral attraction we all have for shapes that are round and sleek. The curved curlews outline is anomalous in this planar landscape, but its colour blends well. The mud is gunmetal grey, the bird brown and the water murky. The sky is dull with a hint of drab. The air is tangy with the smells of decay.

Occasionally the bird wanders a short distance and probes the mud with its beak, sometimes digging it in and twisting it around a little. Every now and then it pulls something clear of the surface, throws back its head and swallows. It is most likely a worm or shellfish, which is consumed without a fight. There is no showiness or drama, no prey is torn apart with dagger-like talons or razor beaks, it is just take a step, probe, suck; take a step, probe, eat and repeat. It is absorbing to watch in its rhythmic motions. Icy gusts tease the birds feathers; at times, the curlew looks like it might be blown off its thin legs, but walk on it does, interrogating the mud beneath its feet.

Observing this self-reliant being in the distance can feel like an act of endurance. The wind is coming straight off the sea, cold and peevish. It finds every buttonhole and cuff, intent on extracting warmth. On this raw day, standing still is not pleasant. It is tempting to move closer, but despite all our inventiveness we have nothing that negotiates deep, cloying mud. Certainly not boots. Besides, curlews are nervous. If you cross an invisible line a few hundred metres away they will take off, crying in alarm. Best to stay in one spot, pressed to the binoculars, and tough it out. In the distance, the water stretches away and merges with the sky grey into grey. The curlew is safe from unwanted encroachments in this shifting, liminal world.

Besides the admiration that you feel that something so insubstantial can withstand the rigours of this unforgiving landscape, you may not be particularly awe-inspired. You might decide it is time to get back in the car and go home, but stay with it something magical is about to happen.

Alan McClure, in the first verse of Schrdingers Curlew, asks the same question. Why keep on watching the curlew visible through his window?

On the face of it, there isnt much about this bird

To stop me in my tracks.

Brown, oblivious, busy with the ground

It totters along on stilted legs

Probing among the frozen fields.

He does keep watching, though, and so will we. There is no sound, apart from the wind over mudflats. Wilderness has its own quality of silence, an ancient, unchanging quiet. And suddenly, for no obvious reason, the curlew takes flight. Its long legs and pointed wings launch it into the air. It soars along the horizon. Its outline resembles a miniature Concorde, purposeful and strong. But it is not the sight that is astonishing, it is the sound. The air is cleaved by a piercing, soul-aching cry curlee, curlee that spreads over land and water. It is at once sweet and painful to hear, following Norman MacCaigs description in his poem, Curlew:

Music as desolate, as beautiful

as your loved places,

mountainy marshes and glistening mudflats

by the stealthy sea.

The pauses between the calls are as poignant as the cries themselves; they define the silence and fill it with expectation and emotion. Given a religious turn of mind, you could almost describe it as a benediction. It is as though the winterscape has been blessed.

Schrdingers Curlew also ends with an epiphany:

And then, untouched by my musings

The bird spreads its wings and lifts,

Naming itself, with a long, pure note

And my heart, in two states,

Leaps

and breaks.

If you havent done so before, you have now met the bird named after a sliver of the moon and the taut curve of an archers bow, Numenius arquata, an everyday sprite, otherwise known as the Eurasian Curlew. At once magical and down-to-earth, this bird is a mysterious prober of dung and earth, mud and meadow.

Both parts of its name Numenius and arquata refer to its most conspicuous, long curved bill. Numenius is the Latinised version of two Greek words, neos for new and mene for moon, that thin shaving of light that is full of potential. Arquata is Latin for the archers bow; taut and stretched into a smooth arc. Numenius arquata, then, is the new-moon, bow-beaked bird.

Eurasian Curlews are Europes largest wading bird. The body is about the size of a mallard duck, but with much longer legs to hold it clear of the water. The small head, supported by a stretchy neck, terminates in that astonishing sickle-shaped bill. They are predominantly brown and grey, but when in flight, the white rump and underside flash against the sky. Eurasian Curlews are found across the European continent, from the west of Ireland through to Siberia; there are thought to be around one million birds in all, but that is only a best guess. Many areas they occupy are remote and difficult to access, so we know surprisingly little about this common European bird.