Copyright page

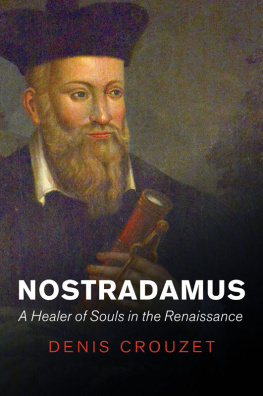

First published in French as Nostradamus. Une mdecine des mes la Renaissance, ditions Payot & Rivages, 2011

This English edition Polity Press, 2018

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300,

Medford, MA 02155

USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0769-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0770-2 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Crouzet, Denis, 1953- author. | Greengrass, Mark, 1949- translator.

Title: Nostradamus : a healer of souls in the Renaissance / Denis Crouzet.

Other titles: Nostradamus. English

Description: English edition. | Malden, MA : Polity, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017006637 (print) | LCCN 2017035325 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509507726 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781509507733 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509507696 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509507702 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Nostradamus, 1503-1566. | ProphetsFranceBiography. | Prophecies (Occultism)FranceHistory16th century. | BISAC: RELIGION / Religion, Politics & State.

Classification: LCC BF1815.N8 (ebook) | LCC BF1815.N8 C75713 2017 (print) | DDC 133.3092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017006637

Typeset in 10 on 11.5 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

Translator's Preface

Denis Crouzet is one of the most distinctive voices among France's early-modern historians. In a sequence of landmark books, he has changed the way we think about religious tension and violence in the period of the post-Reformation, and especially in France. His approach is unconventional, his methodologies unusual, and his style of writing idiosyncratic. Until now, however, none of his major books has been translated into English, and the anglophone world has not had an adequate opportunity to sample his work. That is why I, a historian of early-modern Europe and not a professional translator, offered to undertake this task.

Crouzet's study of Nostradamus provides us with excellent insights into what makes his work unique. The subject is a kind of North Face of the Eiger for the historian, for reasons that Crouzet explains. The resulting book is a non-biography, an essay which attempts to reconstruct the strange mental and emotional world of Nostradamus and his contemporaries (their collective imaginaire the word is translated throughout this text as imaginary). In so doing, he teases the mysterious astrologer away from the myths which surround him and back into a historical context which is coherent and believable. The astrophile (which is how Nostradamus described himself) was trained and practised as a physician, well-known for treating outbreaks of plague. Crouzet explains how he was also concerned to treat the mental and emotional epidemic of his time, the paroxysms created by the religious upheavals of the Reformation. A world in which religion is the subject and object of confrontation is the Ground Zero for Crouzet's analysis of the Nostradamian cogito (or each person's perception and creation of his own existence). The word has been left in this text as in the original, because it is appropriated from the works of the literary critic, Georges Poulet just one of several influences of what is known as the Geneva School of Literary Criticism that emerges in this text.

Crouzet analyses the peculiar, obscure and complex writings of Nostradamus to uncover the philosophical project which lies beneath. He shows how, in parallel with the hippocratic way of treating patients, which looked for ways of preventing the spread of disease, Nostradamus used augury as a method of treatment, and enigma as an instrument of therapy. Nostradamus quatrains become a nebulous form of expression, expressly designed to create a sense of disorientation, a hermeneutic of destabilization, in the reader. Real historical events and invented ones, geographical locations from here and there, Biblical points of reference and Kabbalistic allusions, past, present and future, are all mixed together to create a strange disorientating world in which terrible atrocities and massacres, monstrous births and deformed bodies become allegories for human pride and sin. Nostradamus writes his enigmas as allegories, just as his contemporary Hieronymus Bosch paints them depictions of human folly, blindness and stupidity, a world imprisoned in sin. Nostradamus apocalyptic vision was intended to convey a truth over and above its superficial predictive logic, to create a panic (angoisse the word recurs in this text, and it has often been translated here as angst) in the mind of the reader. That angst was designed to have therapeutic value, to make the reader aware of man's essential weakness. It is at this point that Crouzet associates Nostradamus with some of the essential ways of thinking that eventually fed through into the Reformation movement in France. His shorthand for those patterns of thought is evangelist, and that word has been retained in this translation. There is perhaps no better word to characterize the distinctive blend of Christian mysticism, Biblicism, and unpolemicized sympathy for emerging Protestant theology, which was a feature of the early, pre-Calvinist, French Reformation. I have avoided, however, using evangelism and evangelical to steer the reader away from the associations which the words suggest in their minds with gospellers from different ages and contexts. Readers will discover that Crouzet historicizes Nostradamus by giving him a place alongside Franois Rabelais, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Desiderius Erasmus, and Marguerite de Navarre. I have drawn on translations of their works from the standard editions, as appropriate.

Retaining the distinctive sonorities of Denis Crouzet's writing in this translation has been a considerable challenge. Beyond it lay the ordeal of how best to render the works of Nostradamus himself in translation. The Prophecies have, of course, been translated into English before, and most notably in the seventeenth century by Theophilus de Garencires, a Paris-born physician who moved to England in the 1640s in the entourage of a French ambassador. Garencires initial claim to fame was to warn the world of the dangers of sugar to the human constitution, but it was his edition and translation of Nostradamus (The True Prophecies or Prognostications of Michel Nostradamus

Next page