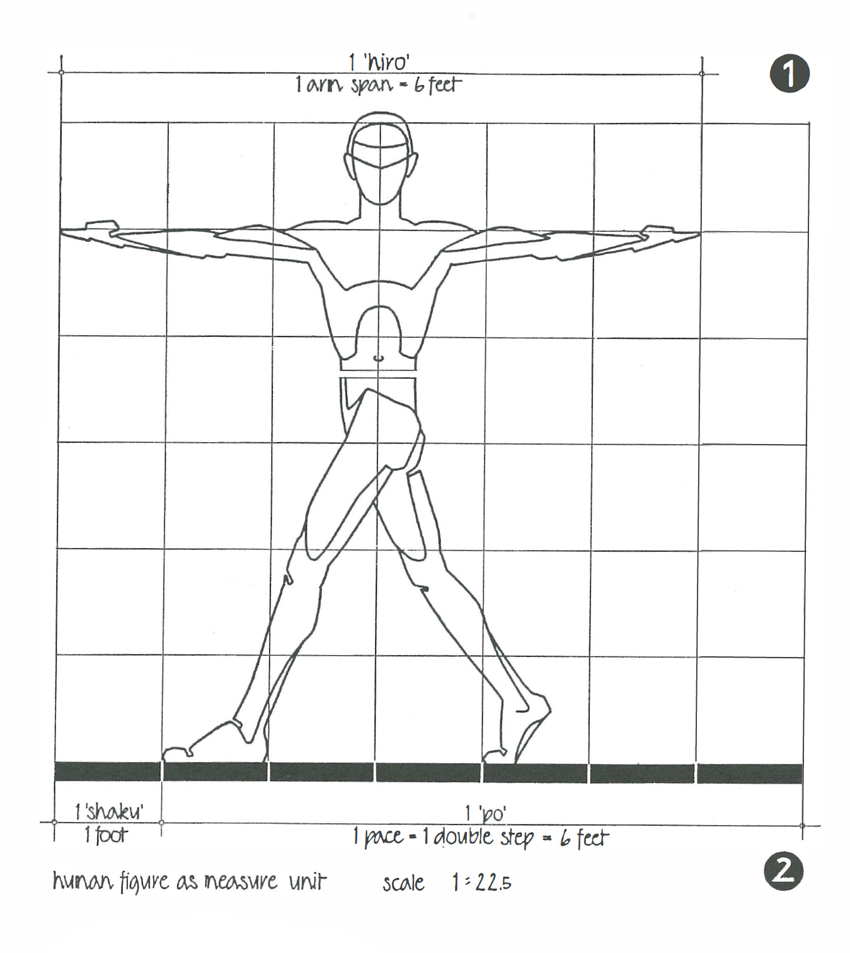

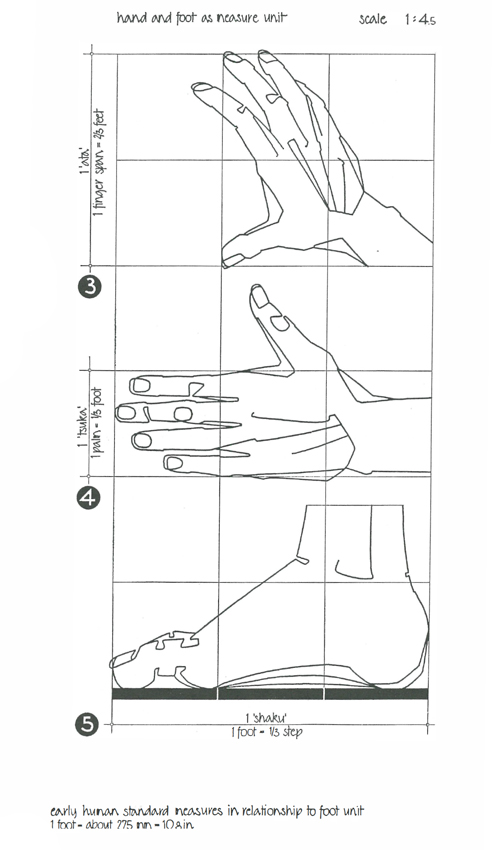

1 measuring system

and module

measure of man

The earliest and most primitive architectural space was the minimum volume required to contain the family. Its dimensions, therefore, were but human measurements in their multiple, modified by interior functional activities and by the limits that material and technique imposed. These basic factors of space in residential architecture have not essentially changed and are also prerequisite to adequate architectural space in contemporary design. This is not meant to challenge the importance of other less primitive-practical factors in the creation of architectural space such as its ideal or psychological aspect. No doubt, these are decisive for the quality of architectural space, but in residential architecture they can only be attributed secondary importance in comparison to the fulfillment of mans mere physical requirements for space, i.e., requirements for sitting, working, and sleeping.

The cause and idea behind space in residential architecture, therefore, is primarily functional-practical and only secondarily emotional-ideal. Of course, space may occasionally function to satisfy mans aesthetic-spiritual wants rather than his physical wants, but the dominant function of space in residential architecture is the fulfillment of mans practical requirements. Therefore, thorough knowledge of the measure of mans physique is essential for both analysis of the existing and creation of the new.

This is of even more importance in the case of Japan, where social conditions have imposed on the common classes the utmost of limitation and curtailment of space in building that has no equivalent in Western architecture. In fact, the relationship of human and architectural measurement is so immensely close that one may well speak of their being identical. It effects a strong interrelationship of man and house and is the major reason why the Japanese house appears dwarfishly small in comparison with Western residences, the difference being far greater than the difference between Japanese and Western figure would indicate.

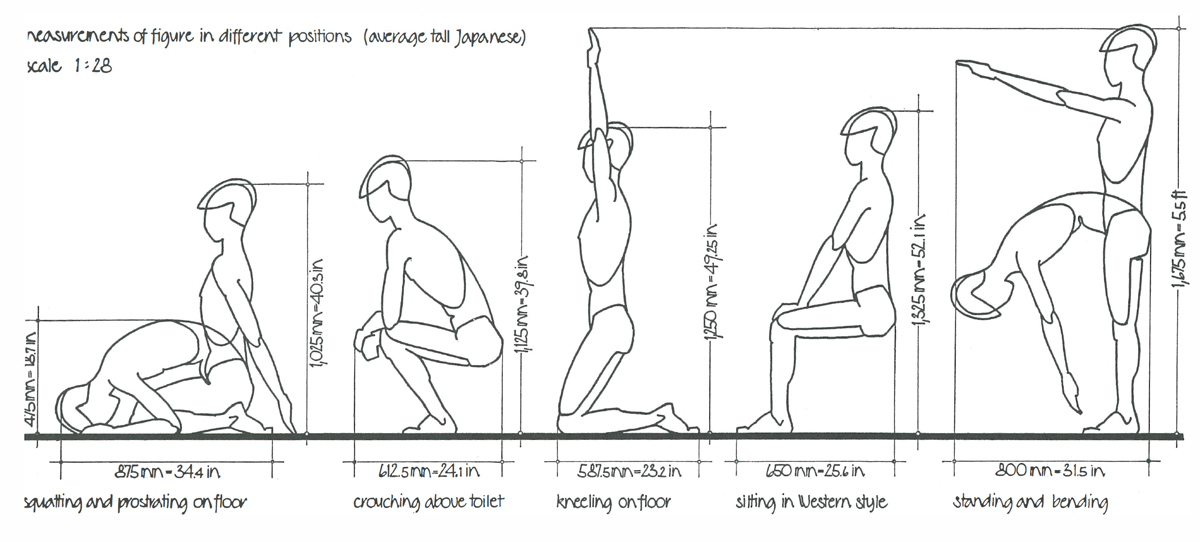

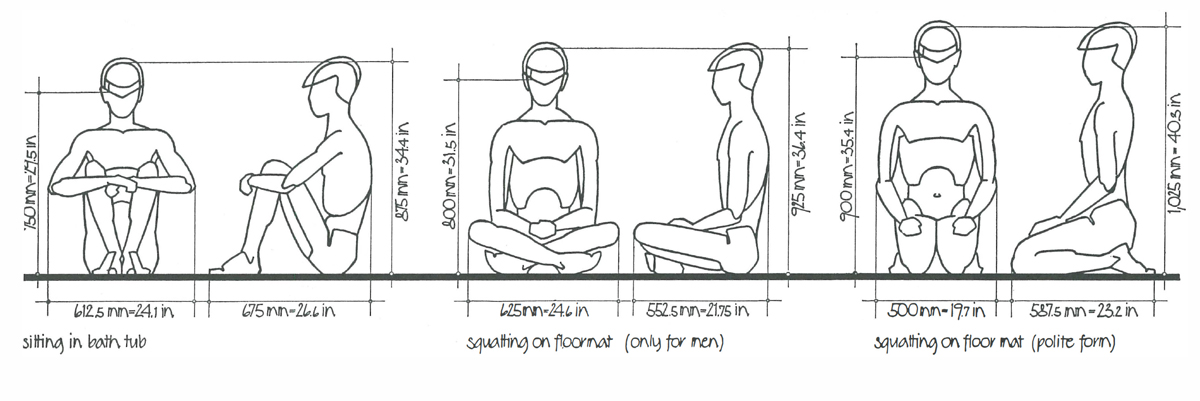

Measurements of the average-sized human have little significance for architectural dimensioning. For building, no matter of what type, is not for the individual alone but for the majority of people. Consequently, architectural dimensioning has to prove adequate for all, i.e., it must be determined by the size of the average tall person so that convenience is provided for all others. Only the height measurements of furniture are exempted, because, here, the measurements of the average small person reversely prove adequate for all others. Therefore, the two extremes, the tall and the small human figure, have to be considered in architectural dimensioning. However, since furniture is very rare in the Japanese house, only measurements of the average tall Japanese are of value.

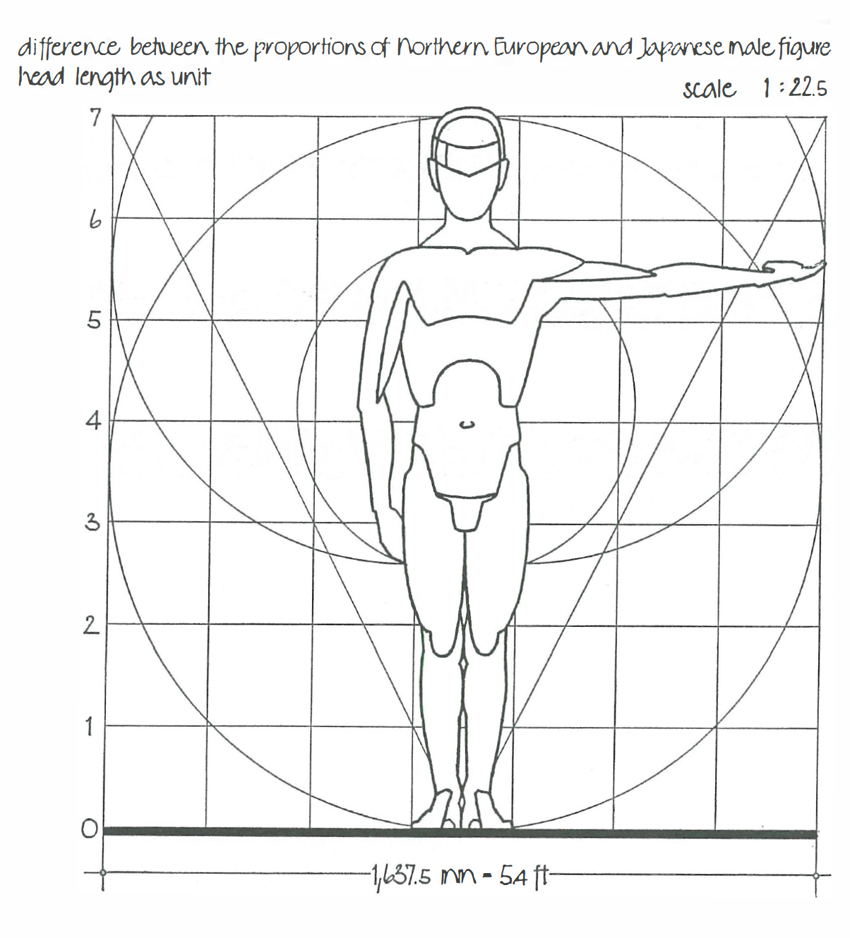

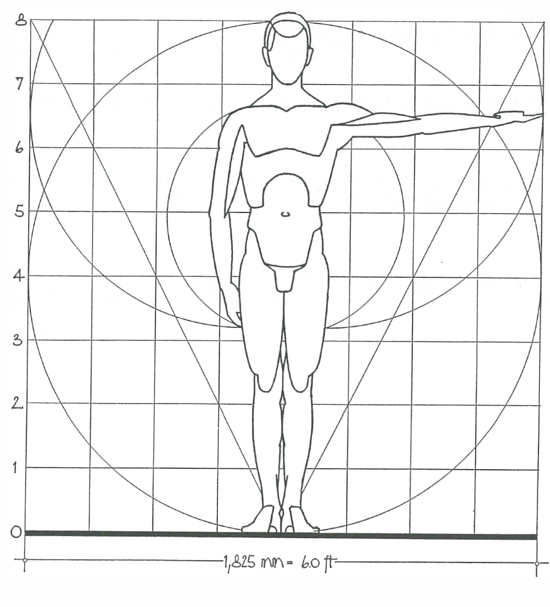

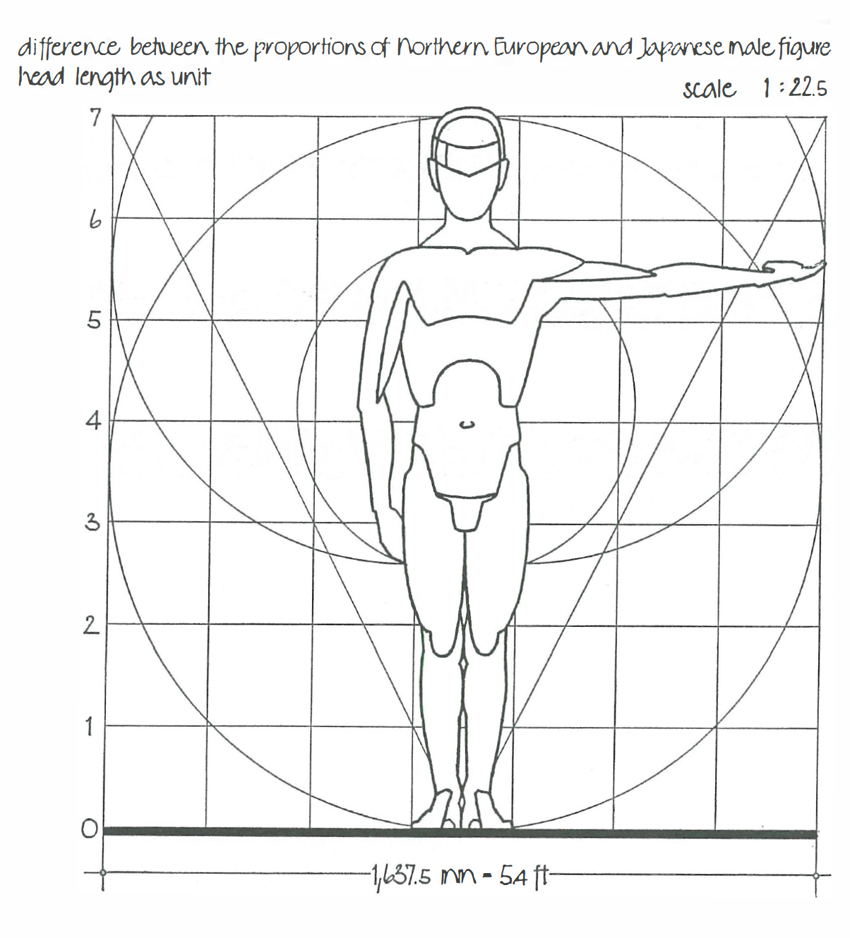

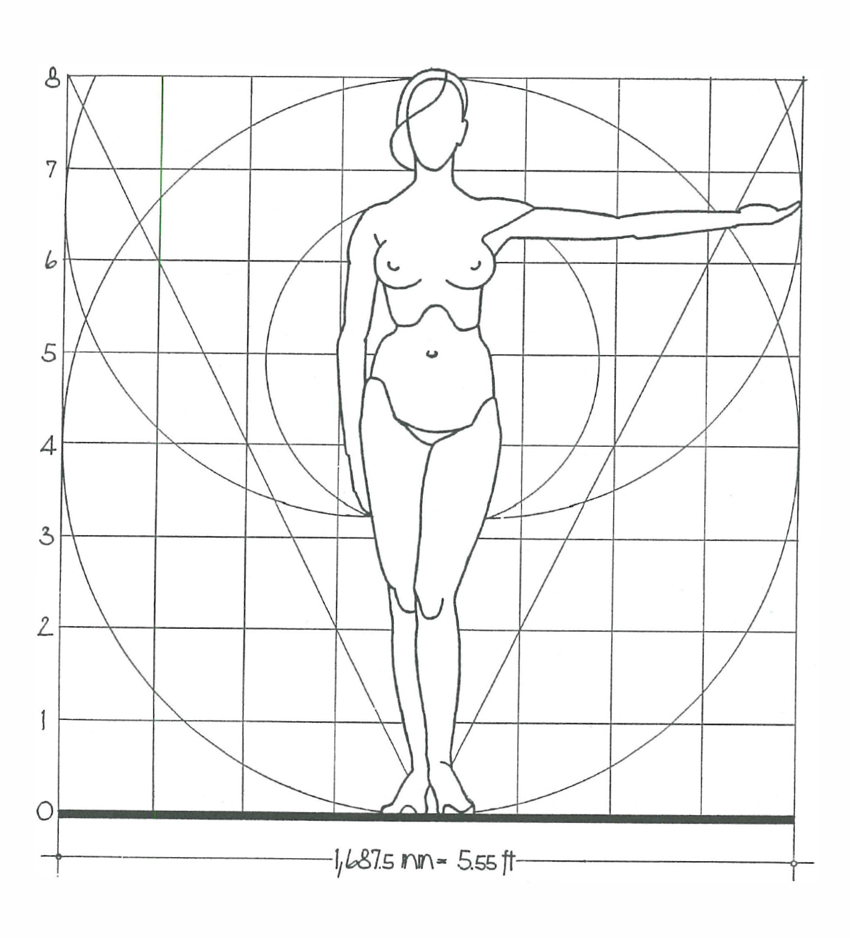

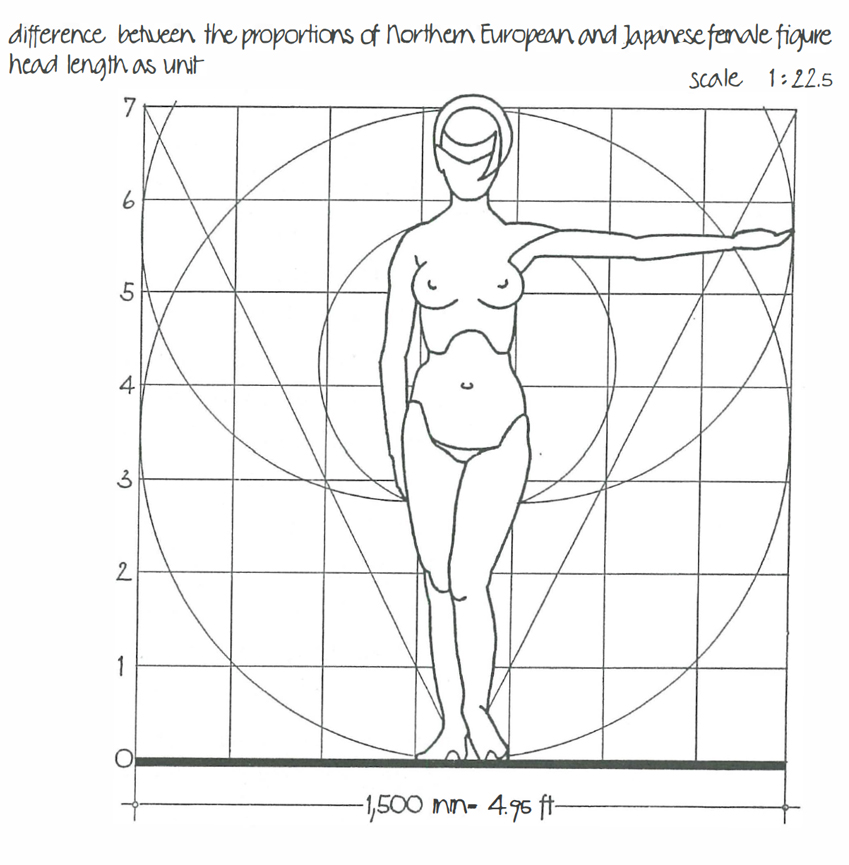

The dominant Japanese physical type is Mongoloid. In relation to the total figure height, the head is large and the limbs are short; also the face clearly manifests the Mongolian type. The main physical differences from the Caucasian type, having architectural importance, are the following:

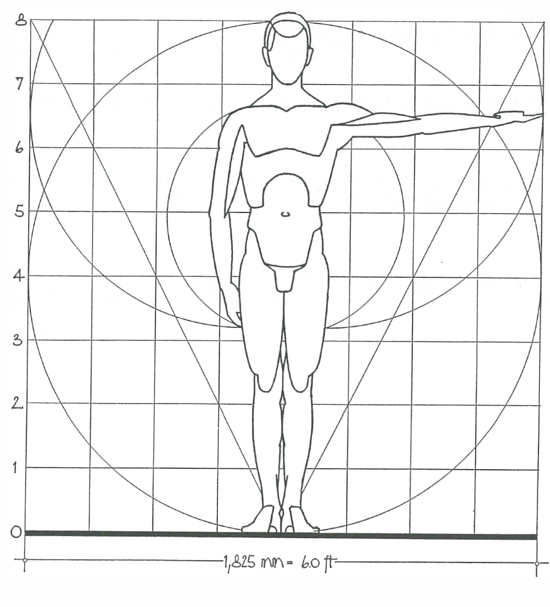

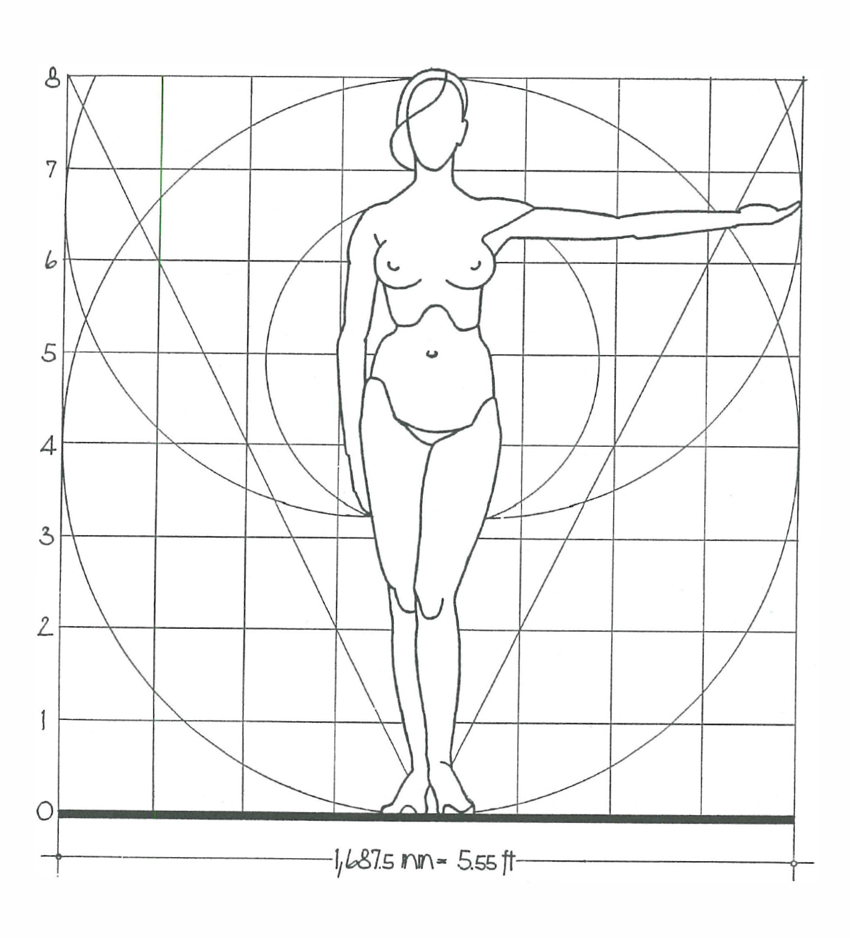

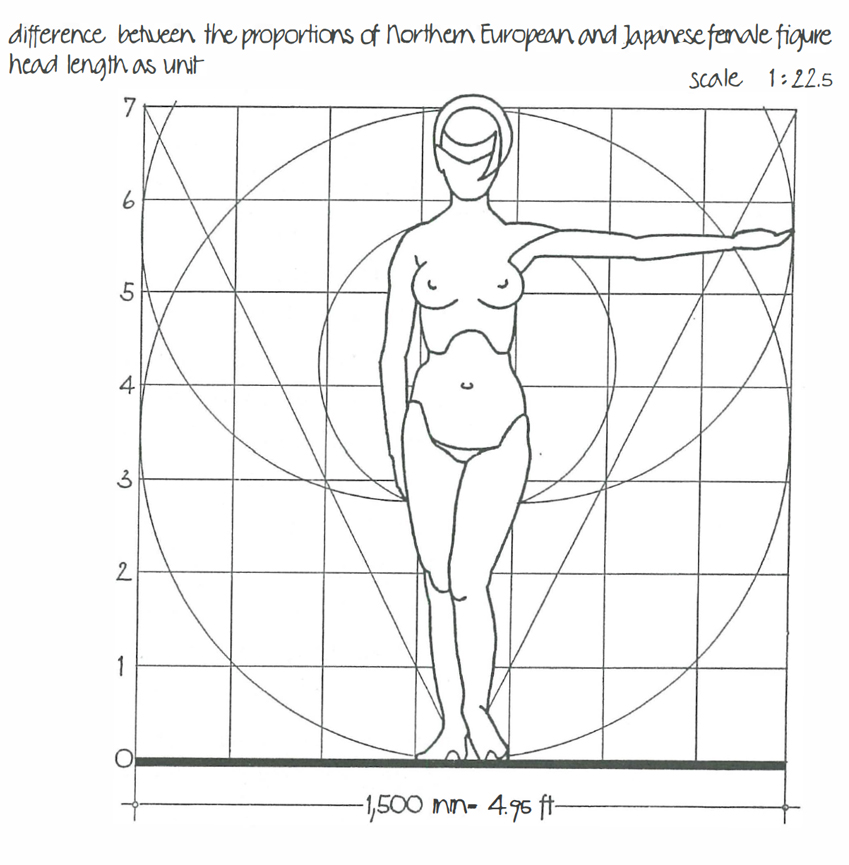

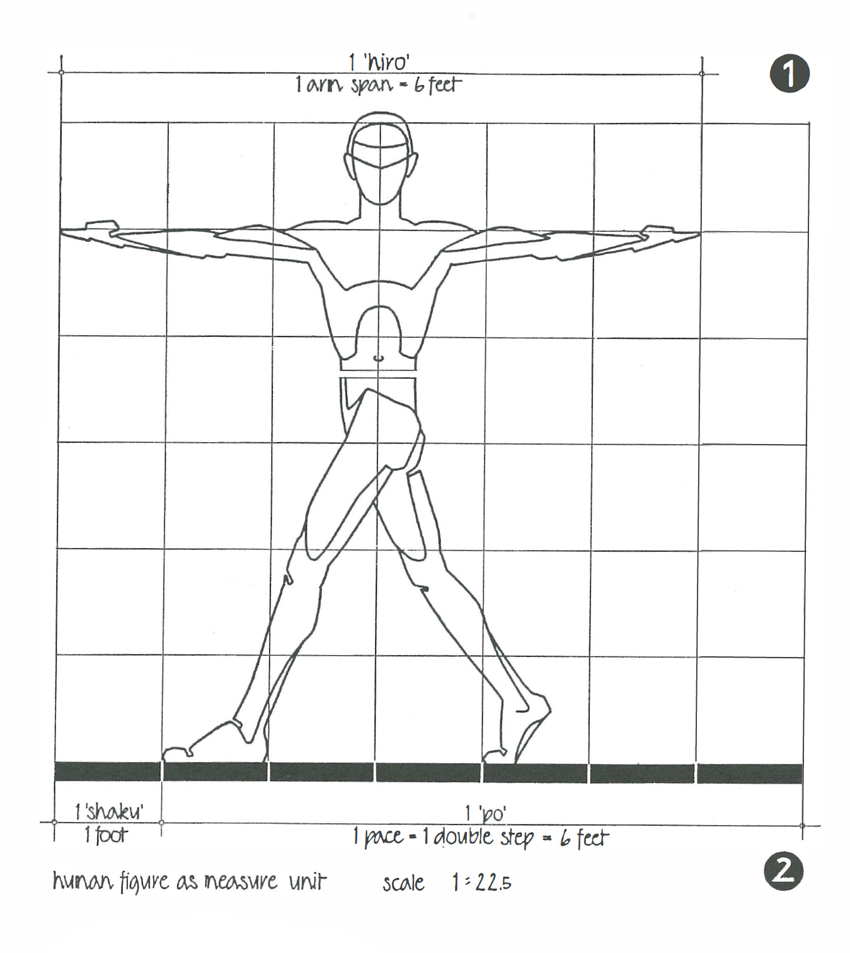

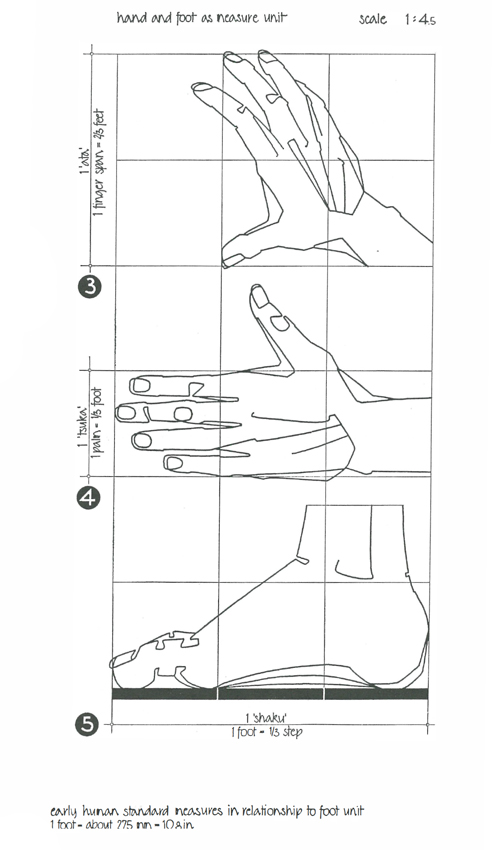

FIGURE 1: The human figure as standard for measure units.

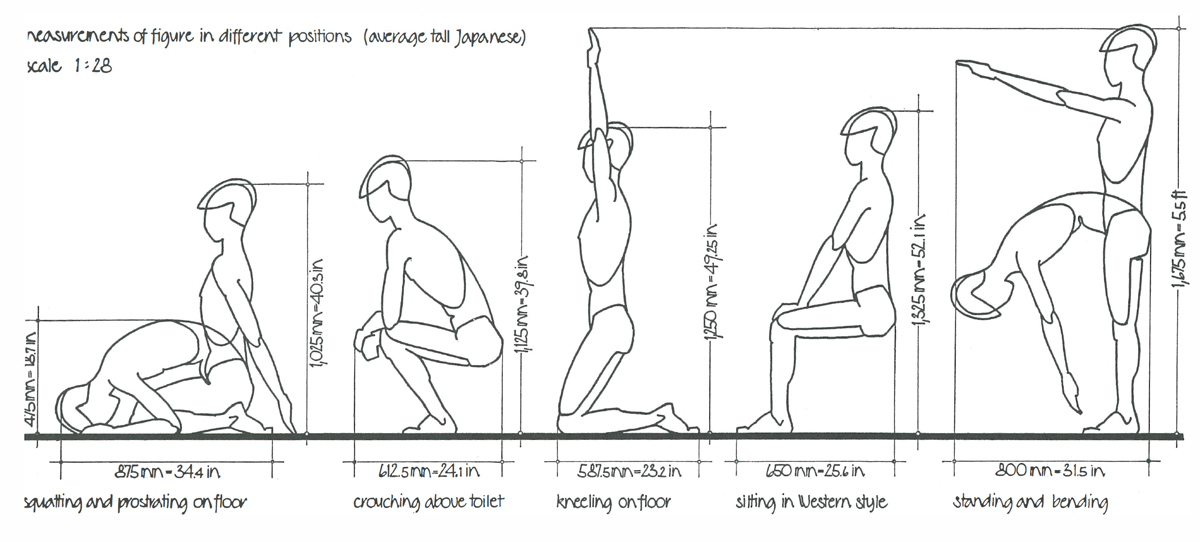

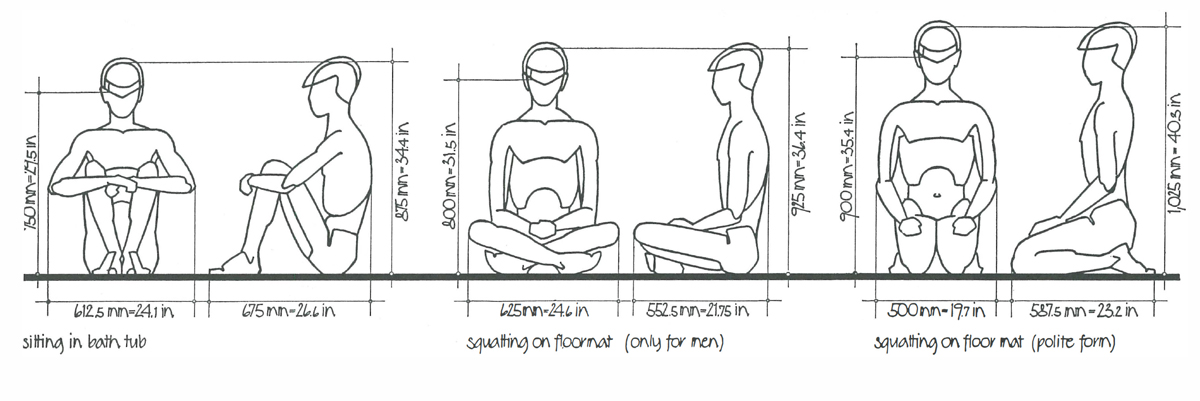

FIGURE 2: Space requirements of the Japanese figure in various postures.

1. The average height is about 6 sun smaller (187.5 mm. =74 in.).

2. The whole body height is between 6 and 7 times that of the head height, while in Western countries the average is 7 to 8 times.

3. The body crotch is much lower than the middle of the body whereas the Caucasian type has the crotch about at half height.

4. This results in particularly short legs and other limbs, which are already shorter because of smaller body height.

5. Thus the torso has about the same height as the Caucasian counterpart, i.e., sitting on the same base, the eye level of both is about the same.

FIGURE 3: Comparison of standard human figures of Northern Europeans and Japanese.

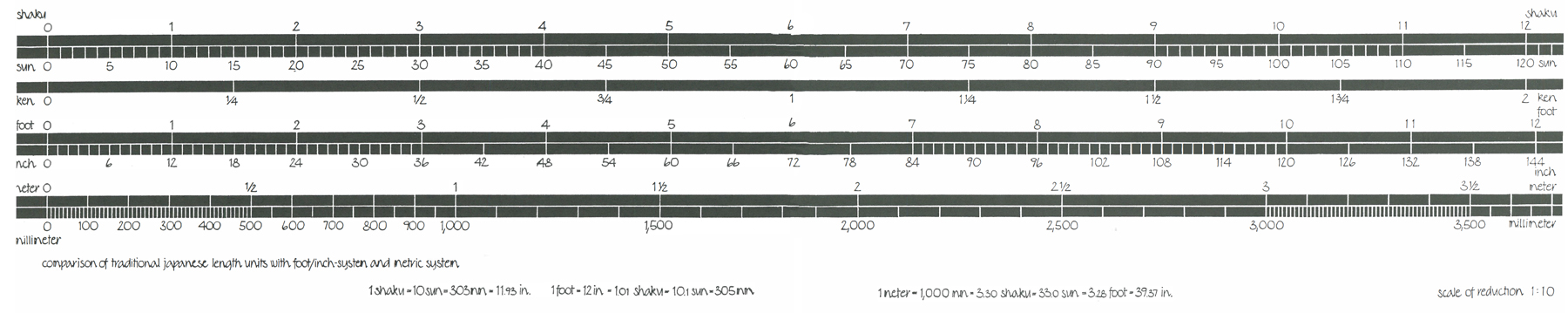

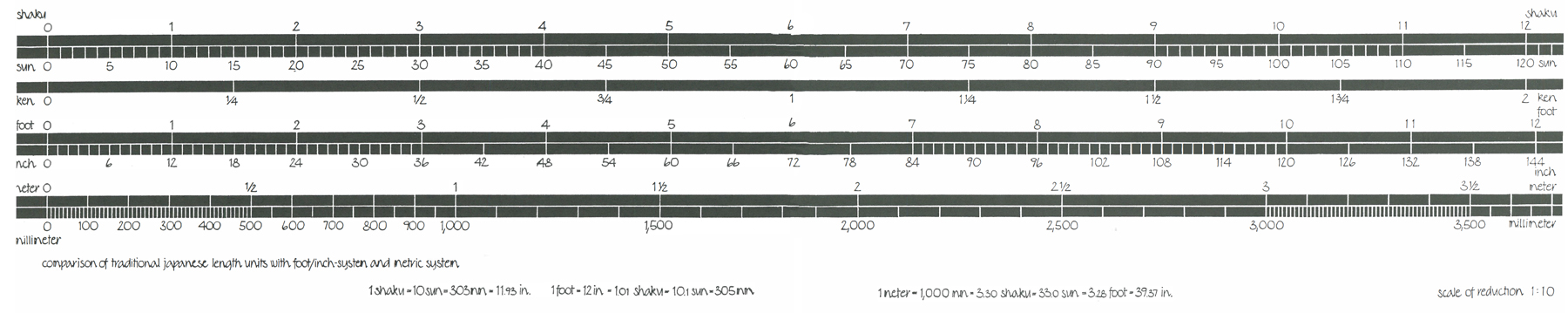

FIGURE 4: Comparative scales for shaku, foot-inch, and metric systems.

building measures

Though in Japan the metric system has been in use since 1891, the ordinary residence is still controlled by the traditional measure system. Its basic unit is the Japanese foot called shaku, almost identical with the English foot. The structure of measures was taken over from China and in its original subdivision was consistently decimal.

ri = 150 j = 1500 shaku

j = 10 shaku = 100 sun

1 shaku = 10 sun = 100 bu

sun = 10 bu = 100 rin

bu = 10 rin

In the latter half of Japans Middle Ages another length unit, the ken, appeared. Ken originally designated the interval between two columns of any wooden structure and varied in size. However, it became standardized in residential architecture very early and was used as a measure unit in the cities. After various transformations the ken finally emerged as the unique design module, although in two essentially different applications: the ky-ma method and the inaka-ma method. Both have affected the measures in residential architecture up to the present time, but only the ken of the inaka-ma method of 6 shaku (1,818 mm. = 6.0 ft.), which relates to center-to-center distance between columns, eventually replaced the j unit of 10 shaku used in handicraft and for common use and was incorporated as the official unit of the Japanese system of measures. The primary reasons for this development were the ken measures intimacy with daily life, its close relationship to human measurements, and its practicality in use.

The Japanese system of length measures is comparatively simple:

ri = 36 ch = 2160 ken = 3,927,165.12 mm. = 12,884.40 ft. = 2.44 mi.

ch = 60 ken = 36 j = 109,087.92 mm. = 357.90 ft.

j = 10 shaku = 3,030.22 mm. = 9.94 ft.

ken (inaka-ma) = 6 shaku = 1,818.13 mm. = 5.97 ft.

shaku = 10 sun = 303.02 mm. = 11.93 in.

sun = 10 bu = 30.30 mm. = 1.19 in.

bu = 10 rin = 3.03 mm. = O.12 in.

The units ri, ch, and j are applied only in field measurements and city planning. Yet, as the construction of cities systematically subjected blocks, streets, and houses to a common order, these large units also affected the single residential site and therefore, though indirectly, the houses too.

While the above length units constitute exact measurements, the Japanese square measures for residences are conspicuous by their vagueness. Two units are used to denote room area, but neither can be expressed in exact measurement.