Diagrams on 2010 by Graham White, NB Illustration www.nbillustration.co.uk/graham-white

For .

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The is reprinted with the permission of The Estate of James MacGibbon.

Every effort has been made to contact and clear permissions with the relevant copyright holders. In the event of any omissions, please contact the publishers.

For Flora.

One chilly February afternoon my three-year-old daughter, Flora, and I were messing around on the rocks in Cornwall. Normally, this would have been a perfect opportunity for some cloudspotting. But that day was unseasonably clear in fact, there was not a single cloud to be seen. And as we sat at the edge of the cove, with nothing but the monotonous Atlantic horizon ahead, we found ourselves, by default, watching the motion of the water. At least, I did. Flora just wanted to clamber about on the slippery boulders.

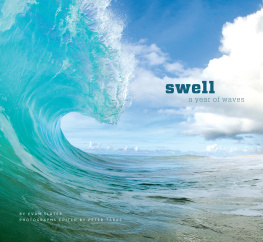

There was nothing dramatic about that days waves. They werent barrelling breakers throwing up clouds of spray as they slammed into the headland. Nor did they have any of the regularity of the waves you see in your minds eye, arriving as a steady succession of crests, one after the other, tumbling in regimented fashion up the shingle.

Im late, Im late, Im late.

In fact, there wasnt the slightest order to the waters motion. Like rush-hour commuters at a busy station, the little crests passed this way and that, crossing each others paths chaotically. But, unlike commuters, they passed through and over each other, combining and dividing, appearing and disappearing.

Their movement was mesmerising. I found myself unable to follow the progress of any individual crest for more than a second. No sooner had I fixed on one than the pesky little peak joined with one coming from a different direction. Then, inevitably, my eye would be distracted by a third wavelet that would sweep through just as the first two vanished.

Talking with Flora, the questions were soon coming thick and fast: Why are there waves?, Where do they come from?, Why do they splash like that? And although they were childish questions, it was me, not Flora, who was asking them.

Although a clear blue sky had triggered my interest in waves, I now realise that cloudspotting leads naturally to wavewatching. You cant stare at the clouds for long before realising how much their appearance is influenced by waves. I dont mean the waves rolling over the surface of the ocean, but the ones that form up there, within the boundless airstreams of the sky. For the atmosphere is an ocean too, but an ocean of air rather than of water.

The oceans above and below the horizon are intimately related. As the Book of Genesis records, the first thing God did, when getting everything started, was to set the seas in motion:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

The following day, He divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. In other words, God separated the oceans below from the clouds above with an expanse of air.

This close affinity, if not common lineage, between sky and sea means that a mere cloudspotter is in fact, without even realising it, a wavewatcher, since clouds are often borne on waves of air.

These waves take the form of rising and dipping winds, which, though invisible, are revealed by the shapes of the clouds. The undulatus species, for example, is either a continuous layer of cloud with an undulating surface or parallel bands of cloud separated by gaps. Such clouds are born in the region of wind shear that occurs between air streams of different directions or speeds. Undulatus is a beautiful, if common, example of the clouds revealing the waves of the atmosphere.

But the most spectacular example of waves in the sky has to be the rare and fleeting KelvinHelmholtz wave cloud. This snappily named formation looks like a long succession of what surfers call pipes or barrels, but are more accurately described as vortices. It is an extreme example of the undulatus species in which the shearing winds are at just the right speeds to cause the cloud waves to curl over themselves. The fleeting formation appears for no more than a minute or two before dissipating. While the processes that form it have little in common with those causing an ocean wave to tumble upon the shore, this cloud surely sits slap-bang in the middle of the Venn diagram of cloud and wave enthusiasts interests.

Cloudspotters and wavewatchers are united by the beauty of the KelvinHelmholtz wave cloud.

A wave cloud, or any other cloud for that matter, is a collection of suspended water particles; but what exactly is an ocean wave? You may think the answer is obvious: it is a moving mound of water. But if you do think that, you are not watching carefully enough. The best way to see that it is not is to observe the effect waves have on something floating in the water a sprig of seaweed, for example.

Before Flora and I abandoned the waters edge, I watched one such tuft of weed rise and dip and duck and weave as it kept pace with the agitated water below. The seaweed seemed less like a rushing commuter and more like a featherweight boxer. As the peaks moved this way and that below it, the bobbing seaweed remained in the same general position. It wasnt swept along with the crests.

When we climbed on to the cliff-top, we watched how a boat moved with the passage of the waves. From up there the waves had a wholly different appearance. The chaotic criss-cross of crests now looked like just a surface texture, which reflected a glittering path of sparkles below the Sun. Beneath these shimmering wavelets, one could see that a far broader, more orderly, pattern of undulations was rolling in towards us from far out in the Atlantic. Each smooth wave was, Id guess, some 1520m from its predecessor, which it followed in a calm, sedate fashion. This caravan of crests could not have been more different from the little peaks that busied across its surface. But, just as they had passed under the seaweed rather than sweeping it along with them, so these gentle giants rolled in under a fishing trawler that was returning with its catch. They didnt drag it towards the land, as they would have done had they been currents of water. Clearly, the water that the boat floated on returned to pretty much where it had started after the wave had passed through.