Like Nothing on this Earth

Tony Hughes-dAeth is a Senior Lecturer in English and Cultural Studies at The University of Western Australia. He has published widely on Australian literature and cultural history, including Paper Nation: The Story of the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, 18861888 (Melbourne University Press, 2001) which received the Ernest Scott and the W.K. Hancock prizes for Australian history. Hughes-dAeth was co-editor of Westerly magazine, a literary journal devoted to Australian and Asian writing and culture, from 2010 to 2015.

Tony Hughes-dAeth

Like Nothing on this Earth

First published in 2017 by

UWA Publishing

Crawley, Western Australia 6009

www.uwap.uwa.edu.au

UWAP is an imprint of UWA Publishing

a division of The University of Western Australia

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. While every attempt has been made to obtain permission to publish all copyright material, if for any reason a request has not been received, please contact the publisher.

Copyright Tony Hughes-dAeth 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Hughes-dAeth, Tony, author.

Like nothing on this earth : a literary history of the wheatbelt / Tony Hughes-dAeth.

ISBN: 9781742589244 (paperback)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Literature and societyWestern AustraliaWheatbelt

Region History.

Creative writingWestern AustraliaWheatbelt Region.

Wheatbelt Region (W.A.)

Cover image taken from Cowans wheatbelt scrapbook, c. 19331934. Peter Cowan Papers, Peter Cowan Writers Centre, Western Australia

Typeset in 11 point Bembo by Lasertype

Printed by McPhersons Printing Group

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface: The Clearing Line

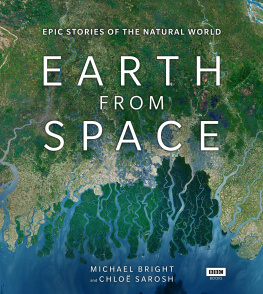

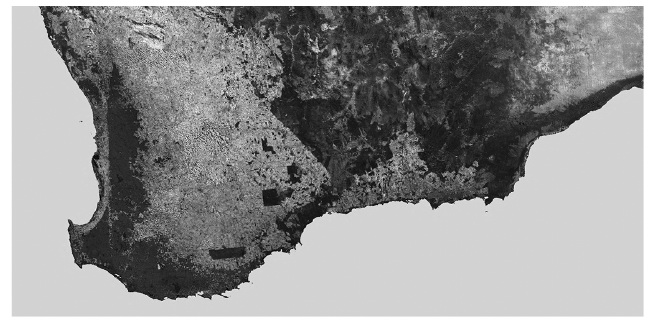

Most nights I watch the television news until the end so I can see the weather report. The presenter stands in front of a virtualised image of Western Australia on which appear, in harmony with her prompts, the various data and signs that allow her and us to participate in the narrative of our states weather. At some point, maybe ten or fifteen years ago, the map of the western half of the continent was replaced with a satellite image which ranged in colour from fawn to forest green. To my nave eye it seemed that the green portions of this map roughly matched the green parts of our state. I was most struck, and have been ever since, by the sharp line that ringed Perth to the north and east, stretching roughly from Geraldton to Esperance and marking out an area most West Australians know as the wheatbelt. Inside the ring was a wheat-coloured yellow, outside the ring a muted eucalyptus green. The line where they meet, known by analysts as the clearing line, is the most obvious visible sign from space of humans effect on the planet. These pixels are abstractions but they are not mere metaphors. They bear a strict relationship to the surface of the land they represent. The pixels are given a colour value based on the degree of reflectance measured by the satellite camera. The more light, the brighter the pixel; the less, the darker. The sharp line is created by the spectral contrast between native perennials (bush) and the crop and pasture grasses that now predominate in the agricultural areas. It is made sharper by the comparative flatness of the country.

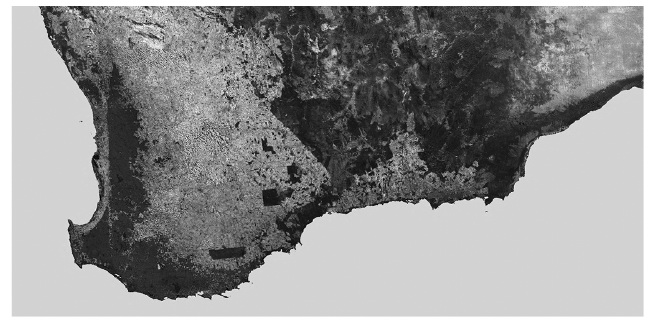

The wheatbelt from space.

The clearing line follows the rabbit-proof fence which also marks (more or less) the minimum rainfall threshold (the 10-inch line, or after the 191718 survey, Brockmans Line), below which cropping is unsustainable. Depending on how you look at this line it is either natural or man-made. Remnants survive only in the form of islanded reserves, large in some terms, but tiny by proportion and without the former continuities that allowed the southwest to operate as a fluctuating bioregion responsive to savage climatic change across aeons.

This book traces the creation of the Western Australian wheatbelt during the course of the twentieth century by considering the creative writing of those who lived in the wheatbelt at various points in their lives and then wrote about that experience. This is what I mean by a literary history: a history of the wheatbelt as captured in the literary works deriving from it. The book approaches this task by following an event/witness model. The event is the creation of the wheatbelt and the witnesses are the creative writers. The creation of the wheatbelt was not felt to be a single event, but instead a gradual and, in lots of ways, natural process that took place over generations. But in the deep time of ecological history, the creation of the wheatbelt was sudden and spectacular. Also, from the vantage point of ecology, the event is not the creation of the wheatbelt, but the disappearance of a vast territory of native wilderness with a biodiversity almost without equal on the planet. So, the creation of the wheatbelt and the destruction of the native habitat that preceded it are one and the same, and constitute the event that this book is tracing. It took place in two main phases, 19001930 (roughly 17 million acres) and 19501970 (roughly 20 million acres), with the Great Depression and the two world wars providing hiatuses in the process. Total land cleared by 1970 was approximately 50 million acres or 200,000 square kilometres. To give some perspective, the land mass of Britain is just under 230,000 square kilometres.

Choosing creative writers as the witnesses to this event deserves some explanation. My own background is in literary criticism and cultural history and I have gradually come to realise the particular value of creative writing as a document of record. The event of the wheatbelt has been traced through the disciplines of agriculture, economics, social history and ecology. It is significant in each of those domains. Literature, though, offers something different, which is the interior apprehension of how life feels to people. The eleven writers I have chosen to focus on take the story of the wheatbelt from its beginnings in the early 1900s to the turn of the millennium. Each has presented a different problem to me and the chapters spend time introducing each writer. The different wheatbelts that come into view in their writing represent not just changes in historical time, but variations in literary genre and the particularities of each writers encounter with the wheatbelt. Some grew up there, left and never returned. Others moved there for work in their early adulthood. Others have had family connections that have seen them return again and again through the course of their life and are able to speak to the changes they have seen take place. It became clear as I wrote that learning about the witness was as important as learning about the event.

Next page