PART I

ARCHAEOZOOLOGY AND SOCIAL COMPLEXITY

editors

Susan D. deFrance and Justin Lev-Tov

PART II

ZOOARCHAEOLOGY AND COLONIALISM

editors

Pam J. Crabtree and Douglas Campana

PART III

ANIMAL TRANSFORMATIONS

editors

Alice Choyke

Archaeozoology and Social Complexity

1. A Birds Eye View of Ritual at the Cahokia Site

Lucretia S. Kelly

Over the last century, and particularly the last 50 years, large quantities of faunal remains have been excavated and studied from sites in the American Bottom, a region in Illinois where the largest Mississippian (AD 10201400) mound center, Cahokia, is located. A large faunal database has been amassed enabling the delineation of significant patterns regarding the use of various species of animals over time. In this chapter I examine the potential ritual significance of several rare bird taxa found at the Cahokia site in two locations separated in time by about 150 years. One area, sub-Mound 51 that dates to the Lohmann phase AD 1050, contains the remains of large communal ritual feasts. The second area, Mound 34 that dates to the Moorehead phase AD 12001275, was a significant locus for special activities, events, and religious ceremonies. I present three lines of evidence, zooarchaeological data, archaeological context, and ethnographic and ethnohistoric accounts of how American Indians in the mid-continent used and regarded the identified archaeological bird species to help elucidate what roles they may have played in ritual and ceremonial activities in the past. The bird remains present also contribute to ongoing studies regarding a significant change in symbolism and ideology in the region at the end of the twelfth century.

Keywords: ritual, bird, Mississippian, Cahokia, symbolism

Introduction

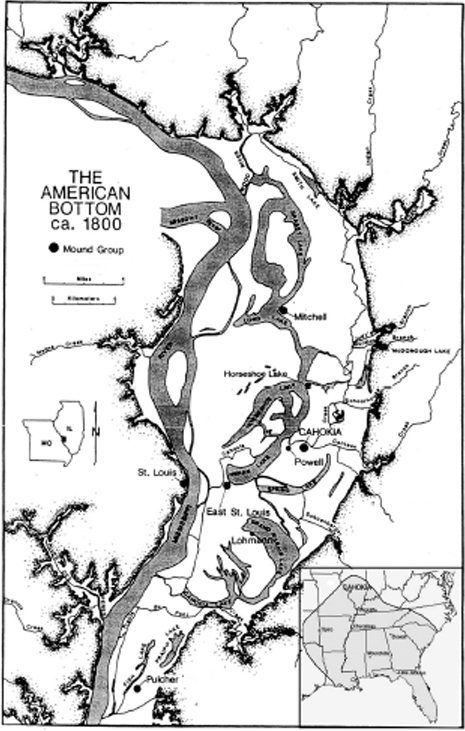

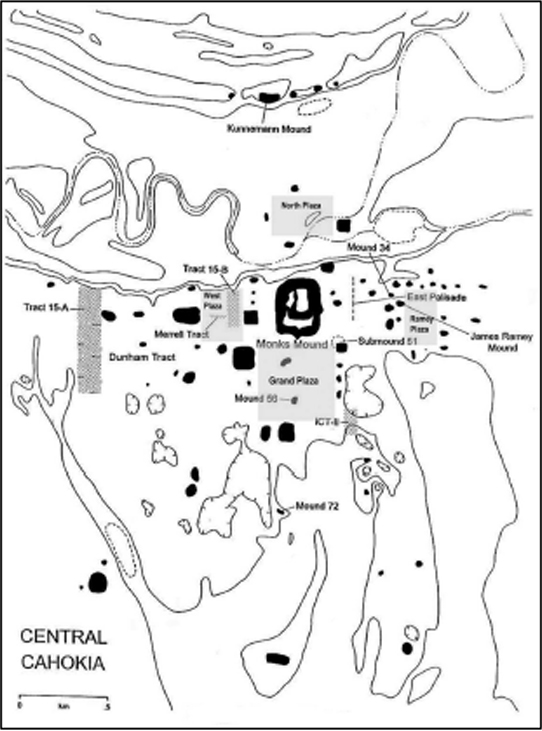

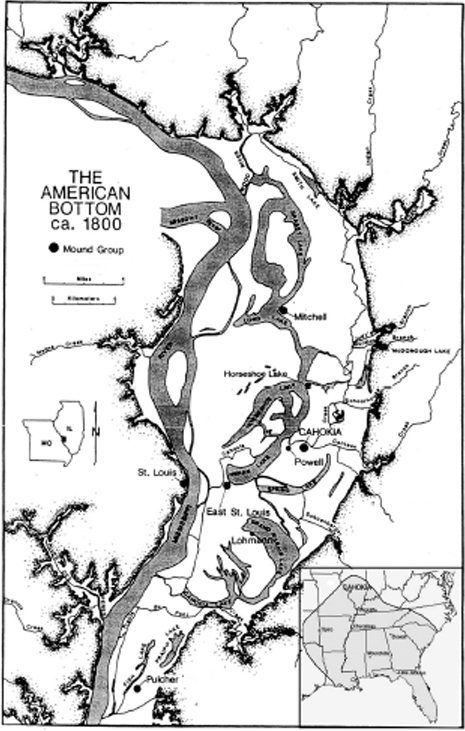

Within the North American mid-continent and southeast, the late prehistoric (AD 10001500) Mississippian Cultural Tradition includes communities that reflect relatively complex forms of socio-political organization, characterized as chiefdoms. They possess common features such as distinctive ceramic technology, the presence of platform mounds and plazas, dependence upon maize agriculture, extensive exchange networks, ranked socio-political structures, and a shared ideology. The Cahokia site, an early Mississippian center on the northern edge of Mississippian development, is located in the American Bottom region of the central Mississippi river floodplain, just east of St. Louis, Missouri (). As the largest Mississippian site with over 100 mounds within a 14 sq. km. area, Cahokia undoubtedly represents the most complex of all Mississippian societies. Over the last century, and particularly the last 50 years, large amounts of faunal remains have been excavated and studied from Cahokia and the surrounding region (Kelly 1997, Kelly and Cross 1984, Parmalee 1975) resulting in a large faunal database enabling the recognition of interesting patterns regarding various taxa of animals over time (Kelly 2000).

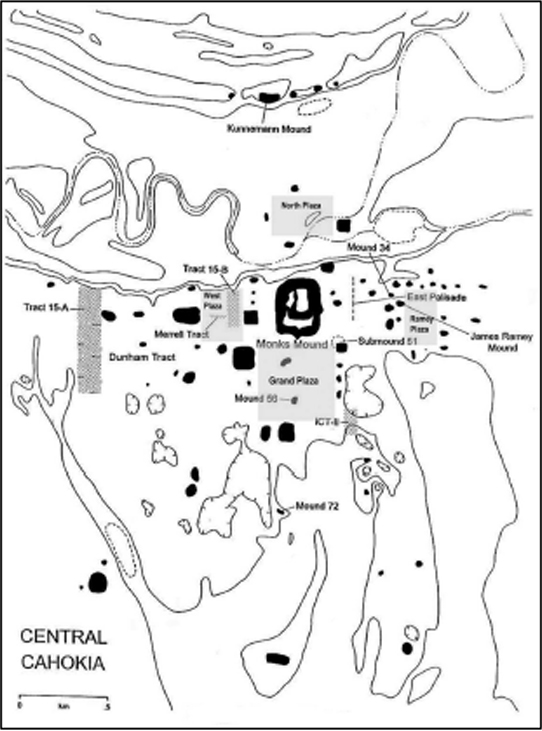

In this chapter I examine the ritual significance of several rare bird taxa found at two locations in the Cahokia site () separated in time by nearly 150 years: sub-Mound 51 dating to the Lohmann phase AD 10501100 contains the remains of large communal ritual feasts (Kelly 2000, 2001; Pauketat et al. 2002) and Mound 34 dating to the Moorehead phase AD 12001275 is a significant locus where special events and religious ceremonies took place (Brown and Kelly 2000; Kelly et al. 2007). I present three lines of evidence to help elucidate the various roles in ritual and ceremonial activities that these birds may have played in the past: zooarchaeological data, archaeological context, and ethnographic and ethnohistoric accounts of how American Indians in the mid-continent used and regarded the identified archaeological bird taxa. The bird remains present also contribute to ongoing studies regarding a significant change in symbolism and ideology in the region at the end of the twelfth century (Kelly et al. 2007), referred to by James Brown (2001) as the Moorehead Moment.

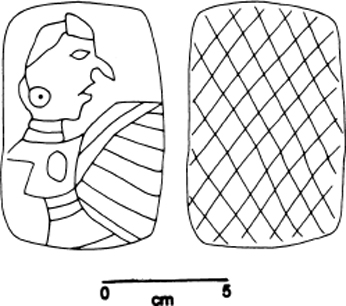

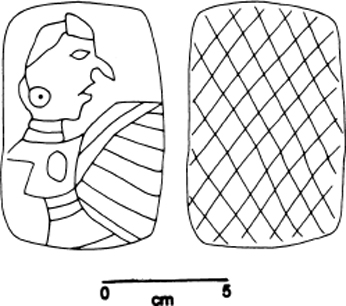

A rich avian iconography exists from the late pre-contact Mississippian period throughout the Southeastern United States, including those of birdmen with hawk or falcon attributes (Brown 2007), owls (Aftandilian 2003), and duck effigies (Kelly 1993). The symbol most associated with Cahokia is a birdman image () found incised on a small sandstone tablet (Williams 1975) that dates late (ca. AD 1300) in the sites history. But, ethnohistoric accounts illustrate that many species of birds played important roles in all aspects of American Indian life. Because Cahokia was abandoned late in the thirteenth century before European contact, there is no direct connection between historic American Indian groups and the inhabitants of Cahokia. Because of striking similarities between Dhegiha-Siouan speaking groups such as the Osage, Omaha, and Quapaw and Cahokian society, some scholars now believe these groups may be the direct descendants of Cahokian populations (Hall 2004, 2007; Brown 2007). Early European explorers that traversed the Southeastern United States came into contact with American Indian societies that archaeologists refer to as Mississippian peoples, and who historically are known as Muskhogean-speaking groups such as the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee. Therefore the Dhegiha-Siouan and Muskhogean ethnohistoric literature are potential sources for analogs to help interpret the birds found at Cahokia.

Figure 1.1. The American Bottom region showing location of Mississippian mound centers, with an insert showing the extent of the Middle Mississippian cultural tradition. (From Kelly 2001, fig. 12.1 with permission of Michael Dietler and Brian Hayden).

Figure 1.2. Map of Central Cahokia showing location of faunal assemblages and plaza arrangement.

Figure 1.3. Birdman tablet from Cahokia Mounds Ramey Tract. (Modified from Brown and Kelly 2000, fig. 4a).

Cahokia Excavations and Contexts

The Cahokia site originally contained more than 100 earthen mounds. Monks Mound stands 30.5 m tall, covers about 67 ha at its base, and faces the 16 ha Grand Plaza (Holley et al. 1993). Three smaller plazas (512 ha) flank its three other sides () (Kelly 1996). On the northeast edge of the Grand Plaza, about 150 m southeast of Monks Mound, stood Mound 51. In the 1960s when much of the Cahokia site was still in private ownership, this mound was removed and sold for fill-dirt. Archaeologists James Porter and Charles Bareis were allowed to conduct some excavation of the mound area prior to the final removal. They discovered that the mound was built on top of part of a reclaimed borrow pit (Bareis 1975). This pit is estimated to have measured at least 50 m north-south and 20 m east-west and was 3 m deep (Chmurny 1973; Pauketat et al. 2002). It was rapidly filled in, possibly within 1 to 3 years by seven very distinct, stratified, fill zones that were quite homogeneous across the pit. Very large amounts of material were needed to create these fills. The animal and plant preservation in these zones was extraordinary, in part because of the very rapid filling-in that created an anaerobic environment (Chmurny 1973; Kelly 2000, 2001; Pauketat

Next page